By: Doug Collins

Evidence from new disciplines like complexity theory tells us that the physical proximity of people, and their everyday interactions, are big drivers of innovation, yet we all too often rely on technology platforms as innovation incubators. Doug Collins, whose day job is advising clients on how to create and build online innovation communities, gets physical.

If you believe that people who live and work in vibrant communities form and incubate the most compelling ideas, then consider the physical environment in which the members of your organization spend their time. This dimension influences the extent to which the organization fosters innovation over the long run.

Here’s an analogy. My work takes me to the new frontier towns that sprouted across the U.S. a couple years ago. Located forty minutes by car from the city center, they combine suburban office parks with lifestyle shopping centers and condominiums, all set on a landscaped green.

One town, or “towne centre” as it has been named, comes to mind. Driving in here I sense that the builders dropped their hammers and ran for high ground as the last, rogue wave of financial crisis crested over them. I have renamed the place Ersatz Village. It contains all the structures that modern civilization seem to need, but possesses none of the energy of an authentic community with living, breathing human beings engaging with one another at many levels through the day.

Ersatz Village comes to mind when I consult with people who help their organizations achieve greater levels of innovation. Our dialogue often starts by exploring near-term measures of innovation effectiveness: Who contributes ideas? Who does not? Do the ideas help the organization overcome its challenges? Are they transformative in nature? Does the funnel that defines idea stages make sense?

Our own experience tells us, however, that when we go down this path without also taking into account the physical environment in which people work, we neglect an important aspect of any innovation initiative. Are we attempting to foster innovation in a dynamic work environment or in the workplace equivalent of an Ersatz Village?

Innovation leaders express surprise when I raise this issue with them. They wonder if their charter extends to the seemingly unrelated worlds of workplace design and facilities management. As an experiment, step out of your office for a moment. Walk the halls. Walk the floors. Where do you experience the most energy? Where do people congregate when they are not directly engaged in the work at hand? What do you see? Do you find yourself in the midst of an Ersatz Village, with each function physically compartmentalized by department, seniority, and rank? Or, do you find yourself in the workplace equivalent of Manhattan’s West Village, pre-gentrification?

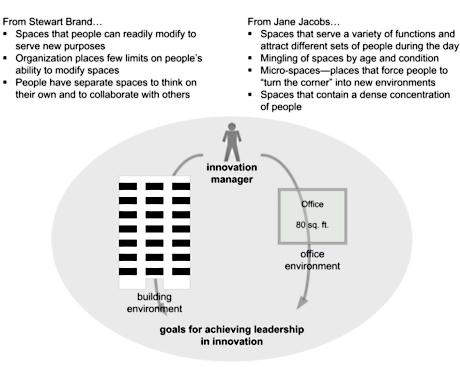

Two writers, in particular, have shaped my thinking on how the organization’s physical space fundamentally influences the potential for innovation: Jane Jacobs, who wrote, The Death and Life of Great American Cities and Stewart Brand, who wrote, How Buildings Learn. Brand explores why and how certain buildings seem to lend themselves to reuse and reinvention over time. Jacobs explores why and how some city neighborhoods persist in remaining vital and inhabited, relative to the “great blight of dullness” that afflicts areas that have undergone urban renewal or other forms of rational planning. Innovation leaders can gain compelling ideas from both.

Brand offers perspective on the value of impermanence—that is, people can more productively explore their creativity when they can, by extension, readily modify their physical surroundings to accommodate their ideas. He offers by way of one example MIT’s Building 20 which the university constructed of wood during World War II to house the team developing radar. As the building was not meant to last beyond the project, nobody objected to its continual, ad hoc modifications over the ensuing 50 years, allowing a who’s who of now famous researchers to pursue their enquiries without the usual amount of administrative interference. The physical attributes of place served as a de facto invitation or prohibition to collaborate and, through collaboration, innovate.

It’s interesting to ask innovation leaders what would happen if they chose to pursue a policy of conscious, structural impermanence within their organizations by tearing down walls and reconfiguring work spaces on the fly to accommodate their initiatives.

Who would object? What price are the sponsors willing to pay in order to accommodate the team’s need to explore new and evolving workplace environments to find one that fosters the level of innovation everyone claims to want the group to achieve? If I had a hammer, I would hammer in the morning, too, long before the facilities supervisor arrived in order to see what sort of change I could create by altering the physical attributes of the environment. To what extent do the people in your organization associate your initiative with the smell of sawdust and spackling compound?

In her classic, Jacobs argues for the need for dense diversity, or for having a large number people pursuing diverse aims yet united in their commitment to a physical, geographical place. Diversity comes from different people entering and leaving the neighborhood for work, for school, for leisure, and for residences. Diversity comes from some people, such as keepers of street-level shops and the neighborhood religious leaders, serving as the nexus of information important to the community as a whole.

Look at your organization’s space from Jacobs’ perspective. Do the accountants sit with the accountants throughout the day, but not the engineers? When and how often do people engage with the people your organization serves? Do you see large swaths of dead space—places ostensibly designed for people to gather but that remain empty? Does your organization have the workplace equivalent of the corner bodega? If so, where is it? Why does it exist there? What information gets traded?

If I were leading an innovation initiative within my organization I would pursue a side project of working through How Buildings Learn with my facilities manager in an attempt to co-opt them to my cause. Make them part of your core team, especially if you need someone on board who is handy with a hammer and screwdriver. Spend time inventing and reinventing your space with them.

Overall, be willing to disrupt the work space if you suspect it needs disrupting in order to foster greater levels of innovation. You face your share of obstacles and objections, of course. Some come in reaction to perceived threats to the current power structure, masked as concerns for safety, ergonomics, and various other forms of corporate policy. Press forward, anyway. Observe what happens Monday after your group assembles a yurt for their collaboration space on the front lawn of the corporate campus over the weekend. At a minimum you gain a better understanding of the degree to which the organization commits to exploring the transformations that authentic approaches to innovation bring.

As a virtual complement to physical space, social media represents a powerful force that increasingly influences how we engage and how we innovate with one another. Yet, collaborative innovation, as enabled by social media, cannot on its own trump dull workplaces that fail to support innovation. Successful innovation initiatives have at least as much to do with enabling ideas to flourish in the physical world as they do in the virtual one. As the leader of your organization’s innovation initiative, you should feel as comfortable grabbing a hammer as you do grabbing a laptop.

In summary, begin your own enquiry on this front by assuming the role of cultural anthropologist. Walk your organization’s neighborhood. Ask yourself where, by location, the most compelling ideas originate today. Make the physical environment part of your charter. Make building new, temporary structures and tearing them down part of the process by which you help your organization achieve leadership in innovation. Lastly, per Jacobs, think about how to chip away at the “great blight of dullness” that exists in the organization’s neighborhoods: the places where the inhabitants have no place where they can think quietly and where they work by internally driven notions of convenience and governance, not by the externally driven influences of how the organization delivers value.

The following figure depicts some of the insights Brand and Jacobs can offer on this subject.

By Doug Collins

About the Author:

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He has served in a variety of roles in helping organizations navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by creating forums, venues, and approaches where the group can convene to explore the critical question. He today works at Spigit, Inc., where he consults with Fortune 1000 clients on realizing their vision for achieving leadership in innovation by applying social media and ideation markets in blended virtual and in-person communities.

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He has served in a variety of roles in helping organizations navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by creating forums, venues, and approaches where the group can convene to explore the critical question. He today works at Spigit, Inc., where he consults with Fortune 1000 clients on realizing their vision for achieving leadership in innovation by applying social media and ideation markets in blended virtual and in-person communities.

Previously, Doug formed and led a variety of front end initiatives, including executive advisory programs for industry influencers, early adopter programs for lead users, corporate strategic planning, and structured explorations of new market and product opportunities. Before joining Spigit, Doug worked at Harris Corporation and at Structural Dynamics Research Corporation which is now part of Siemens Corporation.