By: Altin Kadareja

From incremental to breakthrough innovation projects, managers need to handle different activities and with them dissimilar venues of risks. In this article the internal, external and hidden risks of incremental, differential, radical, and breakthrough innovation projects are identified and ranked accordingly. In addition, for every category a general innovation eco-system has been analyzed.

Throughout this study, risk assessment has been considered “a systemic approach (Cooper and Edgett, 2008) in dynamically organizing and analyzing innovation project’s management knowledge and information for potentially hazardous activities that might pose risks under specified circumstances”. Following this definition, the driver to risk assessment is revealed to be deep knowledge. This transposed into innovation culture within the sector, firm, business unit or individual project manager. Gangadhar Yasam (PMP, PgMP, Ford Technology Services India) has evidenced how innovation culture has supported in risk assessment procedures. In his experience, in one of Ford’s last innovation projects (consolidating applications from acquired companies into the company’s system, incremental innovation project), has led the innovation team to spend additional time during the project analysis phase delivering the project on time and shortly under budget (Gale, 2010).

The driver to risk assessment is revealed to be deep knowledge…

Moreover, several innovation studies have outlined innovation projects as having higher than normal risk, resulting in increasing failure rates (Boulding et al., 1997) and the traditional approach to manage such risks will ignore the underlying attitudes and behaviors that influence the willingness and comfort of the management with higher risk levels (Kumar & Singh, 2006). Therefore, innovation risk assessment will depend on internal innovation culture that one firm has accumulated and risk measurement on methodology used.

For this reason, firms were initially clustered into innovation focus groups and for each group the innovation eco-system and the specific risks impacting the rate of success in innovation projects have been analyzed.

Innovation focus group risks (Incremental – Breakthrough)

Four clusters of innovation projects have been identified:

- Incremental innovation projects – Incremental changes to existing products, projects that are typically focused on line changes or improvements in a firm’s existing product offerings (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996; Ireland et al., 2003);

- Differential innovation projects – New products for the same markets, moderately innovative products for existing markets (Kleinschmidt & Cooper, 1991);

- Radical innovation projects – New products for new markets (Crawford and Di Benedetto, 2002);

- Breakthrough innovation projects – New products that create new markets that usually refer to revolutionary change in firms, markets and industries, which provide substantially higher customer benefits relative to current products in the industry (Urban, Weinberg & Hauser 1996; Christensen and Raynor, 2003; Ireland et al., 2003).

For each of the above innovation projects, the general innovation eco-system (table 7) has been carried out followed by the investigation of specific internal, external and hidden risks.

The table below has summarized the results of the analysis focusing on the characteristics of the innovation activities, propensity to innovate, and organizational strategies for innovation activities.

Table 7. Summary of Innovation related variables among four innovation focus categories: (INC) (DIF) (RAD) (BRE)

Examining the success rate of innovation projects, the results have shown that the firms focusing on incremental innovation projects have been on average 34,43 per cent successful in their innovation projects. Whereas, breakthrough innovation firms have been 40,40 per cent successful in their innovation projects. This difference could possibly be associated with the difference in the relative different investment scale of these type of projects – 8,36% higher Innovation Investments/Net sales in breakthrough innovation projects. Being “new to the word“ the implementation of such innovation type will require a longer time period, which could have been reflected in the number of breakthrough projects undermined by the firms. In fact, looking at the whole population, the average number of “new to the world” projects undertaken by the firms has been only 15, compared to 50 of “incremental” projects.

Breakthrough Innovation firms invest 8,36% more in innovation activities than Incremental Innovation firms.

Referring to the propensity to innovate variables, along all clusters the dominant firm’s attitude toward new inputs has been “Not wait for new inputs, but actively seek them out”. Moreover, looking at the attitude toward innovation, “Innovation: Risk or Opportunity”, the incremental innovators have shown a prevailing consideration of innovation as an opportunity rather than additional risk, while the rest think of innovation as both risk and opportunity at the same time. This result clearly has shown the difference between the incremental innovation firms bearing less risk in incremental product/process lift-ups and the other innovation groups that take a more risk averse position usually dealing with more complex projects.

Lastly, referring to the organizational strategies for innovation activities, when moving from “Incremental” to “Breakthrough”, firms tend to better organize their innovation activities moving from “minimally and somewhat” to “mostly and effectively”. In fact, when organizing for new products that create new markets the innovation activities might entail a higher and different level of training, partnerships, innovation culture, etc. Whereas implementing incremental changes to existing products, firms, relatively need less qualified personnel as well as knowledge sharing within the firm.

How to Turn Crowdsourced Ideas Into Business Proposals

How to Turn Crowdsourced Ideas Into Business Proposals

In October 2020, Pact launched AfrIdea, a regional innovation program supported by the U.S. Department of State. This was geared towards unlocking the potential of West African entrepreneurs, social activists, and developers in uncovering solutions to post-COVID challenges. Through a contest, training, idea-a-thon and follow-on funding, they sought to activate a network of young entrepreneurs and innovators from Guinea, Mali, Senegal, and Togo to source and grow innovative solutions. Learn their seven-stage process in the AfrIdea case study.

Get the Case Study

Incremental – innovation project’s risks

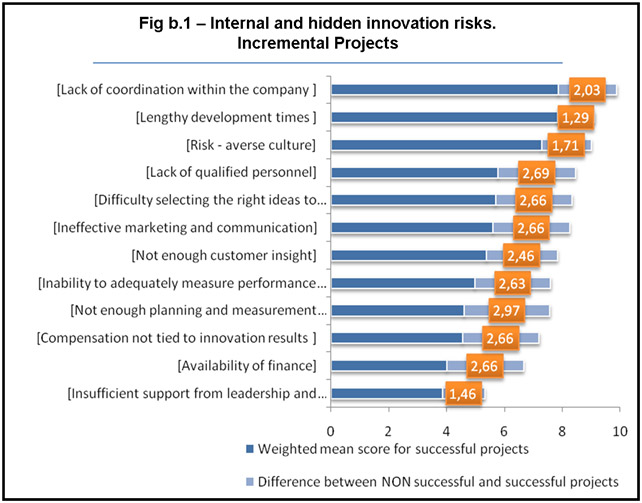

Referring to internal and hidden risks of the incremental innovation firms, results (Fig b.1), have revealed “The lack of coordination within the company” and “Time risk” as the risks that have more significantly impacted the incremental projects to be non-successful. Interestingly, when examining hidden risks (difference between the non-successful and successful innovation projects), “Not enough planning and measurement during the project phase” and “Lack of qualified personnel” lead the list.

Regarding the external risks (fig b.2), the “Uncertainty of the demand for innovative goods or services” and “Not enough customer insight” have been the two most significant risks for this innovation type.

Differential – innovation project risks

“Time risk” and “Not enough Customer Insight” are the two biggest barriers to the differential innovation projects (fig b.3). On the other side, “The lack of qualified personnel” and “Not enough planning and measurement” have been the least significant risks. Referring to the hidden risks, “Not enough customer insight” tops the list, becoming a venue of particular attention for the firms in this innovation focus.

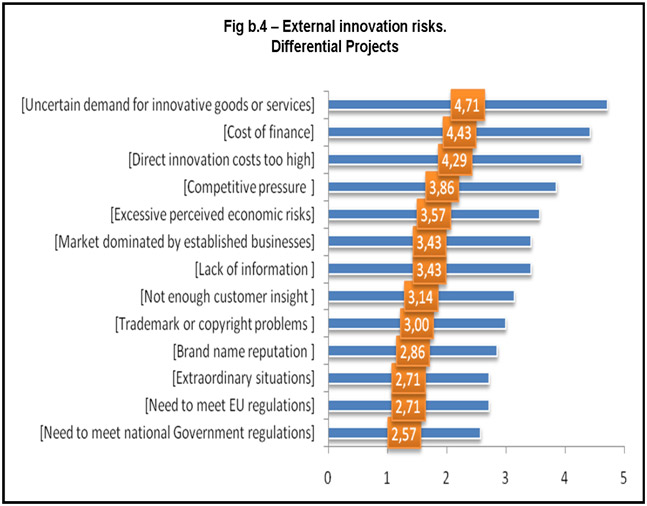

Looking at the external risks (fig b.4) “Uncertainty in the demand for innovative outputs” and “Cost of finance” are the two venues of risks mostly worrying innovation managers.

Radical innovation project risks

For this category, results (Fig b.5), have shown “Risk-averse culture” and “Insufficient support from leadership and management” as the most significant risks. This result clearly underpins the need of firms for a different risk culture and more support from management when the innovation projects become more complex. Looking at the hidden risks, “Insufficient support from leadership and management” is the most dominant risk with a relative big difference from other risks, signaling a very attentive attitude that project’s managers need to pursue toward such risk.

Regarding the external risks of radical innovation projects, “Innovation costs” is the most significant risk reflecting the nature of these projects. Being radical and new, these type of innovations usually will embrace high costs.

Breakthrough innovation project risks

Throughout this category, “the availability of finance” has been indicated as the most significant risk, confirming problems faced due to the large investments of this innovation type (Fig b.7). Concerning the hidden risks, interestingly after the usual “not enough customer insight”, the following most significant risk has been “Difficulty selecting the right ideas”.

On the other side, “market dominated by the established businesses” has been indicated by the firms as biggest external risk (fig b.8). In fact, breakthrough innovations are usually brought to the market by small start-ups firms finding it hard to compete and enter the relevant markets because of the already established incumbent competitors.

Conclusions

From incremental to breakthrough innovation projects, an increasing tendency for higher investments over net sales has been revealed and with it a higher successful rate on innovation projects. Whereas, all innovation clusters have actively sought for new inputs with different degree of risk attitude. Incremental innovators have considered innovation more an opportunity rather than risk and the rest a more risk averse position as both risk and opportunity.

Incremental innovation

The sample of incremental innovation firms, on average, have been successful on 1 out of 3 innovation projects, investing 7.14 per cent of their net sales in innovation activities. In almost 60 per cent of the cases they have not waited for new inputs, but actively sought them out, considering innovation for 43 per cent of the cases always an opportunity rather than additional risk.

Regarding the organizational strategies for innovation activities, incremental innovators have minimally implemented the general innovation strategies (Training, Strategic Innovation, Innovation Culture, Partnership, Innovation Process and Knowledge Innovation Enterprise). These results confirm the nature of this innovation type, widely used as sustaining competitive move, which helps the firms to enrich existing products or processes with new features, without bearing to much risk (Kingsland, 2007).

Results have shown that incremental innovation projects need to be better coordinated within the company, and more dedicated in calculating development times. Moreover, the innovation project’s managers necessitate to very carefully deal with measurement and planning issues during the project phases (hidden risk), as well as before the project starts for better calculating the demand for innovative goods or services.

Differential innovation

The differential innovators have on average been 38 per cent successful and have invested 8.5 per cent of the net sales in innovation activities. They have typically sought new inputs for the 72 per cent of the cases, and usually consider innovation as risk and opportunity at the same time in 43 per cent of the times. In doing so, the organizational innovation strategies for innovation activities have gained importance compared with incremental innovators moving from minimally and not at all (Incremental case) to somewhat and consistently (differential case).

Differential innovators should draw more attention to the customer insight.

Time risk and uncertainty in the demand for innovative outputs have been the most relevant internal risks for these innovation projects. Whereas, attention should be drawn to the customer insight, as the most relevant hidden risk.

Radical innovation

Radical innovators have on average been 39,7 per cent successful on their innovation projects and invested 10,96 per cent of net sales in innovation activities. The relative attitude toward new inputs has been “not wait for them but actively seek them out” in 62 per cent of the cases. Innovation has been considered risk and opportunity at the same time (70 per cent of the cases). Regarding the innovation organizational strategies, these firms interestingly have amplified their efforts moving from “somewhat” to “mostly” confirming the support needed by these kind of projects given the increased novelty level.

Moreover, results have shown that these type of projects need to be mitigated from a risk-averse culture and cautiously plan and organize for the project’s costs. Managers need to carefully sustain the support from leadership and management given the very high and dominant presence this hidden risk has represented.

Breakthrough innovation

Firms under this innovation focus have been 40,40 per cent successful on their innovation projects, investing 15,5 per cent of net sales in innovation activities. The highest rate among the innovation classes. In the same vein with the other categories, they confirm the broad tendency of actively seeking inputs (60 per of the cases) and considering innovation as both risk and opportunity in the same time (60 per of the cases).

Interestingly, the breakthrough innovators have been better organizers of strategies to innovation usually utilizing higher level of training, higher number of partners, a better sustained innovation culture backed by knowledge sharing trajectories within the firm.

Apparently, this innovation type had found difficulties selecting the right ideas to commercialize in the relative markets given the breakthrough innovation products/services characteristics, subject of creating such markets. Moreover, particular attention needs to be drawn upon the financial availability of these kind of projects.

By Altin Kadareja

More articles in this series:

Part 1: What drives a Successful Innovation Eco-System

Part 2: Internal and Hidden Risks of Innovation Projects

Part 3: External Risks of Innovation Projects

→ Part 4: Risks of Incremental, Differential, Radical, and Breakthrough Innovation Project

About the author

Altin Kadareja, MSc, passionate about innovation management has experimented several risk management techniques in innovation projects in Italian banks. Holds a Master of Science degree in Economics and Management of Innovation and Technology from Bocconi University, Milan. Former organizational change consultant focusing on business process re-engineering. An amateur entrepreneur, already founded a start-up and an economic think tank.

Altin Kadareja, MSc, passionate about innovation management has experimented several risk management techniques in innovation projects in Italian banks. Holds a Master of Science degree in Economics and Management of Innovation and Technology from Bocconi University, Milan. Former organizational change consultant focusing on business process re-engineering. An amateur entrepreneur, already founded a start-up and an economic think tank.

References

Boulding, W., Ruskin M. and Richard S. (1997), “Pulling the Plug to Stop the New Product Drain”, Journal of Marketing Research, pp. 164-176.

Christensen, C.M. and Raynor, M. (2003), The innovator’s solution : creating and sustaining successful growth, Harvard Business Press, Cambridge, MA.

Cooper, R. G. and Edgett, S. J. (2008), “Maximizing productivity in product innovation”, Technology Management, Vol. 51 No. 2, pp. 47–58.

Crawford, Merle C. and Di Benedetto, Anthony (2002), New Product management, 7th edition, McGraw Hill, Boston.

Gale, S. F. (2010), “The bigger picture: The trends shaking up the business world are the same ones that can make or break your project”, PM Network, Vol. 24 No.5, pp. 30-36.

Ireland, R. D., Kuratko, D. F. and Covin, J. G. (2003), “Antecedents, elements, and consequences of corporate entrepreneurship strategy”, Academy of Management Proceedings, L1-L6.

Kingsland, B. (2007), “U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration in response to Request for Comments on Innovation Measurement”, Federal Register, Vol. 72, No. 71.

Kleinschmidt, Elko J. and Cooper, Robert G. (1991), “The Impact of Product Innovativeness on Performance”, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 8, pp. 240-251.

Kumar, A. and Singh, R. (2006), “Risk and Innovation – Case for building a Methodology tool to assist informed decision making for Managers”, working paper, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=919180 (accessed 15 March 2010)

Tushman, M.L and O’Reilly, C.A. (1996), “Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change”, California Management Review, Vol. 38 No. 4, pp. 8 – 29.

Urban, Bruce D. Weinberg, and John R. Hauser (1996), “Premarket Forecasting for Really-New Products,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60, pg. 47-60.

Photo by Brands&People on Unsplash