By: Boris Pluskowski

Boris Pluskowski provides us with an overview of the current state of innovation in this guest post.

This is a guest post from Boris Pluskowski, one of the early employees of Imaginatik who has had a ringside seat to observe the evolution of innovation. Boris is currently the author of The Complete Innovator Blog.

Due to the amount of time I’ve been working on innovation I seem to get asked a fair amount of times as to where I think innovation is today. With all of these questions I usually refer back to the adoption curve as a reference point as I find it a very useful tool by which to describe and visualize the maturity of any new concept or tool as there is a similar path by which most follow in terms of adoption by corporations or individuals.

My personal belief based on my experience and recent activities in the market is that innovation – the process of companies trying to innovate on purpose and in a sustainable manner is still a reasonably new practice – is in the adolescent stage of its maturity. If we looked at the track of the adoption curve for innovation as a sustainable business process using the adoption curve, my belief is that it looks something like this:

As I look over the curve and consider key market indicators, I believe that we’re about to begin tapping into the Early Majority stage of the adoption curve now having crossed the Innovator’s Chasm (the make or break point for any concept or product where you have to bridge the gap between the Early Adopters and the beginning of the mass market that is represented by the two majority groups) at the beginning of 2007.

Let me give you some of my reasoning and some of the implications of this prediction:

In 2001, when I first got involved with innovation and idea management, the firm I represented (Imaginatik) was definitely selling to Innovators. They behaved in typical Innovator fashion – looking for shiny objects, reading up on research to get the latest and greatest in whatever business tools were available. They had very little sensitivity to risk and were usually regarded as mavericks within their companies.

Companies today are very different. While there are many more companies aggressively looking to embrace innovation, fewer will make such a drastic leap, because the price to do it right– both financial and otherwise – and the associated risk level of failure have increased exponentially, and will likely continue to do so.

What this represents over the last seven years is the slow but steady maturation of the innovation market – and with that, changes in not only who’s doing innovation, but also how they’re doing it, and what they’re trying to achieve.

In 2001, there were really only a few very small idea management vendors in the marketplace. They were highly fragmented and tended to focus on niche elements of the innovation arena. I remember speaking to an industry analyst from Forrester at the time who told me that despite the fact that they loved our product, “If you don’t have competitors, you don’t have a market.” We were missionary sellers to a market that didn’t know what we had or how to use it – and when they did use it, they tended to focus on using it to replace the “old school” system of paper-based suggestion boxes and Excel spreadsheets. It was hard to find someone who could understand the potential in what we were trying to sell them – and even harder to find someone willing to look at committing the time, energy and resources into making it sustainable. Only serial entrepreneurs and mad men would have dared to enter the market at this point.

By 2004, several more vendors had arrived on the scene. The market became more identifiable, vendors began to string applications together to make more robust products that corporate clients could understand, and I had that same Forrester analyst now tell me that “Consolidation will happen in this marketplace – I know of a company who is going to buy you soon.” At this point there started to be people who “got it” on a more regular basis – although they still tended to be predominately mavericks or “movers and shakers” in the company who were out to make an impact and saw an opportunity to do something no one else had. This, paradoxically, led to a boom and bust period for corporate innovation programs as these maverick leaders would make a big impact in the business world and then have to face the consequences – namely either:

a) Get Promoted

b) Get given more areas of responsibility in order to kibosh their rebellious ways

c) Get hired by someone else in their industry who wanted the magic formula

d) Retire (because another frequent profile of sponsors were that they were in the autumn stage of their careers; they wanted to make a last-ditch impact and had nothing to lose)

This would leave a no-win situation for any potential well-qualified candidate interested in taking over as the potential reaction they faced was either:

1) “Of course you were successful – you’d have to be an idiot to mess up the successful program that [Insert Previous Leader’s Name] started up!”

Or worse – they did mess it up, in which case it was:

2) “You idiot – you messed up the successful program that [Insert Previous Leader’s Name] started up!”

As a result, the only people who would take on the role were junior people without the sufficient expertise and influence needed to be successful and the program would slowly die. It was, incidentally, to break this cycle that Imaginatik eventually began to offer structured certified training courses: to encourage companies that they should no longer rely on a single person for the long term success, but instead provide a structured learning and career path for a the broader segment of the employee population.

The idea management market today is very different yet again – with a multitude of small vendors starting to flood the market. Financing is becoming easier because investors are beginning to actually understand what is meant by the various terms that are used in the marketplace, and what the value proposition is to prospective customers.

Enterprises as a whole are starting to understand, and it doesn’t take them long to figure out how idea management tools and services can be useful to them. Prices are high, but so are the rewards for sustainable innovators – and the current recession is only going to strengthen the innovation agenda (see my blog entry for more on recessions and innovation).

The way companies are embracing and practicing innovation is also changing – the biggest being:

The Change in Innovation Leadership: In the early 2000’s avant-garde companies keen to show innovation leadership in a recessionary period decided to appoint Chief Innovation Officer roles to in a bid to show that dedication to this recession-busting discipline. Since then, most of these roles seem to have disappeared and it’s not that the role is no longer required – but rather that the way innovation is required to be perceived has made the position obsolete. Innovation has to be about helping the organization achieve a direction and goal that it WANTS to achieve – and ultimately there is only one person in the organization that has the ultimate responsibility for that – the CEO. This issue is covered in more depth in my blog post, The Death of the Chief Innovation Officer.”

In the gap left behind by the Chief Innovation Officer’s departure is the vice president of innovation – the new guardian of innovation within the company. This is a senior-level position, populated by executives who are dedicated to ensuring the company is innovating effectively, sustainably, and in the direction the organization needs to go in, and ensuring that a constant stream of new sources of competitive advantage and shareholder wealth are being discovered.

Cross-Functional Awareness: In the early 2000’s, innovation was usually the sole domain of R&D or marketing. Today, innovation is being actively encouraged and sought out in all parts of organizations and even between companies and other external entities. Companies are expecting innovation everywhere and are embracing it from anywhere. Single dimensional approaches are viewed as insufficient, because the pace and complexity of change and innovation are increasing as companies go in search of differentiating factors that will set them apart from their competitors in lasting and effective ways.

Value and Goal Focus: In the past, companies would be pleasantly surprised if they achieved new sources of value. The price point for experimenting with innovation was low, and the expectations were similarly low (I remember one FMCG company I worked with back in 2002 whose idea of a success story was pointing to the new names for the conference rooms that their employees had collaboratively devised). In contrast, today’s innovative enterprise has an almost ruthless and programmatic approach to goal- and value-based innovation as they realize it represents the future of the company. Success metrics are rigorously attached to bottom-line figures and the creation of new forms of organic value, and ROI targets are in high multiples with most companies targeting 3x or more as a baseline.

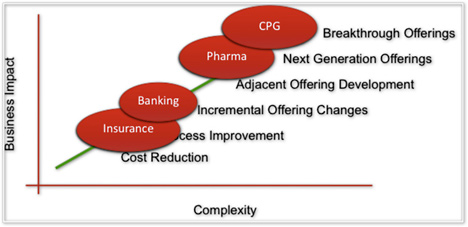

Moving up the Innovation Complexity Curve: Companies today are quickly moving up the Innovation Complexity Curve, each time tackling more complex projects that have an increasingly high potential impact on the business (see this blog post for more details). As one would expect, it is the industries that typically face a quicker pace of change that are leading the charge up this curve as their need for innovation is stronger than most due to aggressive competition.

All of this points to an enterprise landscape where innovation is seen as a critical element of business strategy. It is no longer treated as an experimental venture, but a strategic CEO-supervised initiative. It has senior process leadership and senior project sponsors for each individual project run. There are now explicit goals and metrics tied to the bottom line welfare of the company.

Failure is no longer an option, and the failure to create new forms of value for the company is a matter for very serious concern, partly because failures are more costly today. As a result, experienced innovation heads are becoming increasingly valuable and companies are also increasingly looking for external advice and guidance from consultants and vendors who can lead them by the hand to demonstrated success. All of these trends I’ve described will continue to intensify, because a company’s ability to innovate sustainably today determines whether it is tomorrow’s Apple Corp or yesterday’s Betamax.