There are a lot of wonderful books on creativity and there’s no need here to try to repeat or even summarize them, but there is one aspect of creativity that is not often discussed in the vast literature, and I want to highlight it because it’s pivotal to evoking creative behaviors from individuals and groups, and to achieving innovative results from organizations. This is the creative process itself.

In our work we’ve found that there are more effective and less effective ways to guide and support the pursuit of creative ideas, and the intent of this discussion is therefore to outline a useful structure for creativity, keeping in mind, of course, that like the innovation process, the creative process model described here shouldn’t be followed rigidly.

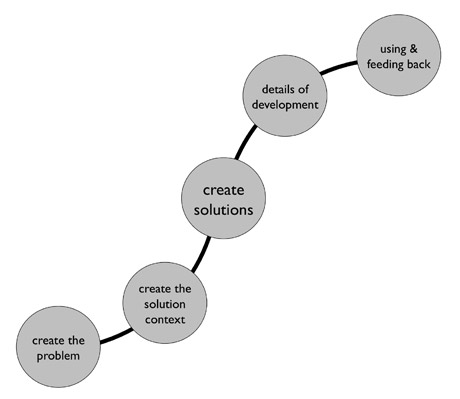

The creative process model

Although each individual approaches creativity intuitively, and therefore differently, there is nevertheless a universal process, a discipline, which suggests something far different than the common stereotype of the wild-eyed creative (mad?) genius working in a cluttered laboratory on a dark and stormy night. Einstein with a tidy haircut might not inspire the same awe, but with his hair exploding in all directions, surrounded by the apparent chaos of papers piled high, or standing in his frumpish sweater beside rows of unintelligible blackboard formulas, this is the creative genius!

Despite the compelling imagery, however, the real secrets to real creative genius are disciplined hard work and a sound underlying model that tells you how to go about it.

The key to the creative process model is a simple distinction, the principle that creativity doesn’t start by looking for solutions, it starts by creating the problems that are to be solved.

Start by creating the problem

When Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed “I have a dream!” he condemned the realities of segregation and racism, and simultaneously expressed his determination to overcome them. His powerful voice still echoes, transcending time and distance.

President Kennedy proclaimed a commitment to send men to the moon, and eight years later astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped from the Eagle and extended the reach of humanity further into the universe.

The protesters of Tiananmen Square were driven by a vision of Chinese society that compelled them to risk their lives attempting to create it.

And on the day that Nelson Mandela was released from 27 years of imprisonment he said, “Today the majority of South Africans, black and white, recognise that apartheid has no future. It has to be ended by our own decisive mass action in order to build peace and security. The mass campaign of defiance and other actions of our organisation [referring to the African National Congress] and people can only culminate in the establishment of democracy. I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities.”

Today, individuals throughout the world persist in their own quests to fulfill their own visions, and whether they live in northern Africa in Tunisia and Eqypt for example, and the Americas, and across South Asia, the voices of past visionaries, of Dr. King, Tiananmen Square, and President Mandela and many others still echo.

A compelling vision, well expressed, is one of the most powerful of forces in the human experience. It sets up the contrast between what is and what could be, and because of this contrast there emerges a stark and driving force, a compelling motive that we call “creative tension.” This is the energy that drives visionaries, whether they are artists or statesmen, scientists or entrepreneurs or educators, missionaries or presidents, revolutionaries, or parents. And it is from this energy that problems worthy of being solved are created.

Great leaders define visions that express the spirit and the potential of their times and by doing so they infect others with a compelling tension that suffuses the atmosphere and begs for action. Such a vision contrasts so strongly with the current condition that the idea of what could be is overwhelmingly powerful, magnificent and motivating, so much so that people may willingly sacrifice a great deal in the quest for its fulfillment. It becomes the defining element of a professional life or perhaps a personal life, and gives meaning to what might otherwise be a mundane existence.

Vision is the key enabler of creative genius, the ability, or willingness, or indeed the compulsion to see things not only for what they are, but for what they could be. This difference is the source of creative tension. In the arts, the sciences, in education and civil service, and in business, people who experience creative tension are intrinsically motivated and often feel compelled to make change, when they want to and even sometimes against their better judgment. They aspire to bring to reality that which they have imagined or envisioned, and consequently they work with dedication and persistence to overcome the obstacles they may encounter along the way.

World-renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp expresses her experience of creative tension this way. “I was fifty-eight years old when I finally felt like a ‘master choreographer.’ The occasion was my 128th ballet, The Brahms-Haydn Variations, created for the American Ballet Theatre. For the first time in my career I felt in control of all the components that go into making a dance – the music, the steps, the patterns, the deployment of people onstage, the clarity of purpose. Finally I had closed the skills gap between what I could see in my mind and what I could actually get onto the stage.”[1]

That gap between the mind’s eye and what it the physical eye beholds is a dynamic, electric place, a powerful source of motivation and momentum, and harnessing this difference as a creative force in your organization is what the creative process model offers.

[1] Twyla Tharp. The Creative Habit, Simon & Schuster. 2003. p 232.

About the author:

Langdon Morris is a co-founder of InnovationLabs LLC, one of the world’s leading innovation consultancies.

Langdon Morris is a co-founder of InnovationLabs LLC, one of the world’s leading innovation consultancies.

Langdon is also a Contributing Editor and Writer of Innovation Management, Associate Editor of the International Journal of Innovation Science, a member of the Scientific Committee of Business Digest, Paris, and Editor of the Aerospace Technology Working Group Innovation Series.

He is author, co-author, or editor of eight books on innovation and strategy, and a frequent speaker at innovation conferences worldwide. He has lectured at universities on 4 continents.

The Innovation Master Plan: The CEO’s Guide to Innovation is now available at Amazon.com.