By: Langdon Morris

Investors in all types of assets create portfolios to help them attain optimal returns while choosing the right level of risk, and innovation managers must do the same for the projects they’re working on.

Innovation is inherently risky. You invest money and time, possibly a lot of both, to create, explore, and develop new ideas into innovations, but regardless of how good you are, many of the resulting outputs will never earn a dime.

Is that failure or success? It could be both. The degree of failure or success will be determined not by the fate of individual ideas and projects, but by the overall success of all projects taken together. Hence, the best way to manage the risk is to create an “innovation portfolio.”

Just as investors in all types of assets create portfolios to help them attain optimal returns while choosing the level of risk that is most appropriate for them, you’ll do the same for the innovation projects you’re working on.

So what do you do? You allocate capital across a range of investments to obtain the best return while reducing risk, and then you manage each project aggressively to make it work.

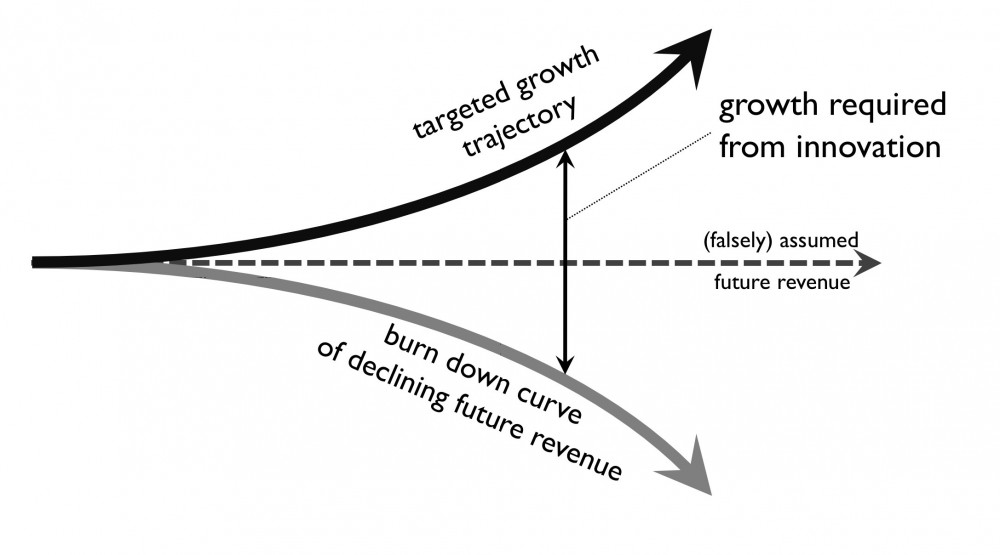

The underlying principle of portfolio management is that the degree of risk and the potential rewards have to be considered together. In a rapidly changing market, the nature of innovation risk is inherently different than in a slower-changing industry such as, say, road construction, because the faster the rate of change in a company’s markets, the bigger the strategic risks it faces. The faster the change, the more rapidly will existing products and services become obsolete, a factor we refer to as “the burn down rate.” The faster the burn down, the more urgent is the innovation requirement.

Burn Down & Targeted Growth

The vertical line represents the magnitude of the innovation challenge.

This will necessarily affect the composition of an innovation portfolio by inducing a company to take greater risks in innovation its efforts. Hence, the ideal innovation portfolio of each organization will necessarily be different: Apple, NASA, Genentech, Union Pacific, GE, and Starbucks are all innovative organizations, but when it comes to their innovation portfolios it’s obvious that they cannot be the same in content or style.

A further key to the dynamics of a successful portfolio is described in portfolio theory, which tells us that the components of a portfolio must be non-correlated, meaning that various investments need to perform differently under a given set of economic or business conditions. In the case of innovation, “non-correlated” means that every firm needs to be working on potential innovations that address a wide range of future market possibilities in order to assure that the available options – and here is the key point – will be useful under a wide variety of possible future conditions.

What we’re really talking about are five different portfolios.

The need for broad diversity in the portfolio also reminds us we need to develop all four types of innovation, so what we’re really talking about are five different portfolios. There will be a different portfolio for each type of innovation, breakthroughs, incremental innovations, new business models, and new ventures, and there will be a fifth portfolio that is an aggregate of all four.

We should also note that each different type of portfolio will be managed in a different process, by different people, who have different business goals, and who are measured and possibly rewarded differently. Hence metrics and rewards are inherent in the concept of the portfolio, and the master plan also calls for the design of the ideal metrics by which the portfolio should be measured. (A set of possible metrics will be discussed in chapter 6.)

This sort of “failure” is a positive enhancement of our likelihood of our survival and ultimate success.

And because we’re preparing for a variety of future conditions, its obvious that some of the projects will never actually become relevant to the market, and they will therefore never return value in and of themselves. But this does not mean that they are failures; it means that we prepared for a wide range of eventualities, and some of those futures never appeared, but we were nevertheless wise to prepare in this way. This sort of “failure” is a positive enhancement of our likelihood of our survival and ultimate success, so it’s not failure in a negative sense at all. By analogy, I carry a space tire in my car, but it is not a failure if I never have occasion to use it.

Therefore, the process of creating and managing innovation portfolios cannot be managed by the CFO’s office as a purely financial matter. Instead, the finance office and innovation managers are partners in the process of innovation development. Hence, innovation portfolio management is like venture capital investing, early stage investing where it’s impossible to precisely predict the winners, but nevertheless a few great successes more than make up for the many failures.

And the CFO will also have to accept the idea that the mandatory investments in innovation mean investing in learning. During the early stages of the development of an idea, its future value is almost entirely a matter of speculation. As work is done to refine ideas in pursuit of business value, the key to success is learning, as the learning shapes the myriad design decisions that are inevitably needed. The innovation process as a whole therefore seeks to optimize the learning that is achieved, and to capture what has been learned for the benefit of the overall innovation process as well as the portfolio management process. This costs money, which cannot and should not be avoided.

As the projects that constitute an innovation portfolio mature and develop, they provides senior executives and board level directors with increasingly attractive new investment options. By managing their portfolios over time, a team of executives can significantly improve the portfolio’s performance; as they engage this type of thinking they get more in sync with the evolving market, and better at identifying and supporting the projects that have greatest potential.

Still, many will fail. In fact, a healthy percentage of projects should fail, because failure is an indication that we are pushing the limits of our current understanding hard enough to be sure that we are extracting every last bit of value from every situation, and at the same time preparing for a broad range of unanticipated futures.

About the author:

Langdon Morris is a co-founder of InnovationLabs LLC, one of the world’s leading innovation consultancies.

Langdon Morris is a co-founder of InnovationLabs LLC, one of the world’s leading innovation consultancies.

Langdon is also a Contributing Editor and Writer of Innovation Management, Associate Editor of the International Journal of Innovation Science, a member of the Scientific Committee of Business Digest, Paris, and Editor of the Aerospace Technology Working Group Innovation Series.

He is author, co-author, or editor of eight books on innovation and strategy, and a frequent speaker at innovation conferences worldwide. He has lectured at universities on 4 continents.

The Innovation Master Plan: The CEO’s Guide to Innovation is now available at Amazon.com.