Each order claims its universality, its orthodoxies, its adherents, and its malcontents. Switching sides can bring drama for the order and trauma for the heretic. What do you need to get right, whether you pray on Friday, Saturday, or Sunday?

Behold, the Lean Startup

Steve Blank published, “Why the Lean Start-Up Changes Everything,” in the Harvard Business Review.

Reading his piece, I found my mind pondering in parallel the following thoughts:

- he gets at the essence of the practice of collaborative innovation

- he serves me new wine in old bottles.

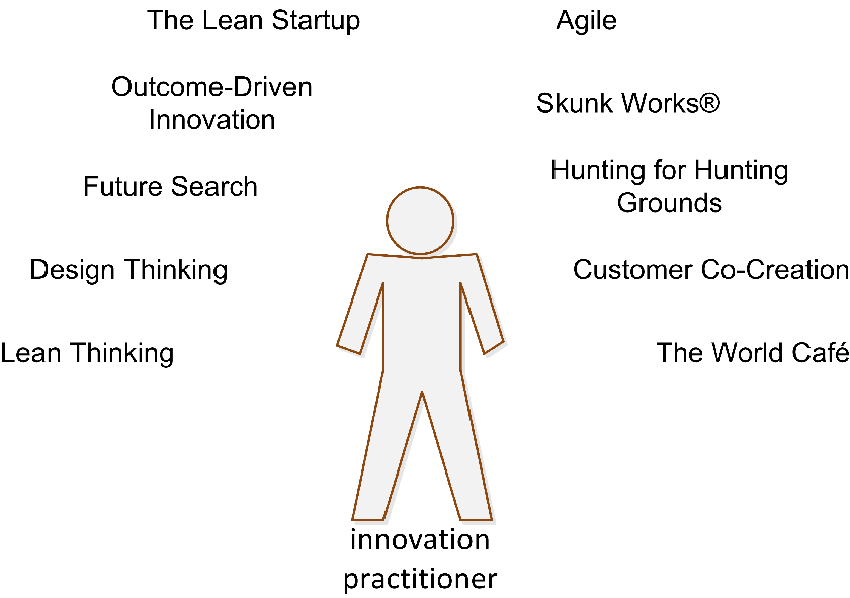

In our work to find a meaningful way forward in the Digital Age, we have developed so many approaches to getting at innovation that we risk confounding the good soul who wants to move beyond the idiocy of forecasting cash flows five years into the unknowable future of a billion dollar market that has yet to be birthed screaming into existence in order to focus on building something that someone, somewhere, may value enough to pay her some small sum, signaling to her that she is on the right path or, if she finds that she is not on the right path, that she can correct her course before she wastes more of her limited, valuable time.

In this article, I speak to the essential elements that comprise an effective approach to the practice of collaborative innovation: embracing empiricism,embracing the big picture, and embracing personal leadership.

Embrace these three well and you are well on your way. Fail to embrace them and each new means of pursuing collaborative innovation will seem like the flavor of the month.

Embracing Empiricism

Contemporary approaches to collaborative innovation demand that their disciples discipline themselves by asking the critical question: What problem is worth solving?

Design thinkers segment this question into What is? What if? What wows? What works?

Creators of lean start-upstake the same approach, only with a Calvinistic nod to thrift: Let us spend the bare minimum needed to test our hypothesis.

Outcome-driven innovators—the Ulwickians—come at this question by asking themselves: What jobs are to be done? To what extent are people satisfied with the ways in which they can complete the jobs in question today? How important are those jobs to the people?

As with any system of belief, the various approaches share a common understanding of the value in pursuing the larger question, What problem is worth solving? They vary in the methods that they prescribe for the pursuit. Some, such as lean, are quite rigorous. Others, such as agile and the World Café, are by design organic. They assign the highest possible value to self-governance as a pre-requisite to discovery. Good things will happen if we can just get in a room together with the right, representative group of people.

The questions for you, the novice: Do you feel confident in forming a hypothesis? Do you feel confident in understanding how best to go about proving or disproving that hypothesis?

If yes, then you are headed in the right direction.

Embracing the big picture

All approaches, in defining their respective notions of universality, provide their adherents with a means to define the big picture. Often, in moments of charity, they assign a comparable approach to a subordinate role—one piece to the bigger plan. People who pursue lean start-ups position agile as a small means to their larger end. I suspect the good people who have evolved agile into a comprehensive approach were not consulted.

The lean start-up’s map of choice is the business model canvas. Lean practitioners have the A3. The Future Search people have their wall map of the past, present, and future, which they create together over the course of days. The outcome-driven innovators have their hierarchical mapping of jobs to be done.

The questions for you, the novice: Do you have a way of telling the story of your journey on one sheet of paper? Does this piece of paper tell you have been and where you need to go—explore—next?

If yes, then you are headed in the right direction.

Embracing personal leadership

Where all these approaches to collaborative innovation differ from conventional notions of organizational life is that they put you, my friend, in the driver’s seat. You form the critical question. You follow a path of exploration to figure out whether you hypothesis is correct. You tell the narrative of your journey.

The practice of collaborative innovation by its nature involves and engages many people: most notably, the people you believe will benefit from your innovative work. At the same time, the practice of collaborative innovation in all its forms places a premium on compelling personal leadership in the way that the Peter’s envisioned—Koestenbaum and Senge, that is.

The questions for you, the novice: Has it sunk in that if you, personally, are not moving things forward, then things will not progress? Has it sunk in that the Digital Age has given you an unprecedented number of ways to move things forward as an expression of powerful, personal leadership?

If yes, then you are headed in the right direction.

Parting Thoughts: Take A Ride with Me

Where I live a network of narrow-gauge rail lines radiates out to the countryside like the veins that pencilthe back of an old woman’s hand. Some of these lines have been turned into bicycle trails.

My wife and I ride these trails on the weekends when the weather turns warmer and the trees come into leaf.

Thesetrails take us past the serenefront lawns of small, liberal arts colleges founded by ministers of denominations intent on bringing civilization to the wild in the early nineteenth century. Their vision remains a work in progress.

I love these trails. I love these colleges. White pillars and brick, they go about the quiet business of educating new generations of young people in serious enquiry. What does it mean to ask a good question? What does it mean to bring people into the narrative of the question? By what means do we resolve the question?

The fear that at times cycles in the back of my mind is that, as we reconsider what makes for a valuable university experience in the Digital Age, we overlook the value of the serene liberal arts college and the gifts that it brings softly to society’s table.

All approaches to collaborative innovation demand that its adherents, above all else, think: think deeply and think well. The wheels of progress grind to a halt if we begin to produce generations unschooled in asking—and pursuing—the critical question.

By Doug Collins

About the author

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations big and small navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by developing approaches, creating forums, and structuring engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the process and ideas that result.As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations big and small navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by developing approaches, creating forums, and structuring engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the process and ideas that result.As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Today, Doug works at social innovation leader Spigit, where he consults with clients such as BECU, Estee Lauder Companies, Johnson & Johnson, Ryder System and the U.S. Postal Service. Doug helps them to realize their potential for leadership by applying the practice of collaborative innovation.

Image From Shutterstock.com