In this article, innovation architect Doug Collins explores what it means to facilitate an innovation challenge by using a blend of in-person and virtual forums. How might the professional facilitator, in serving as a catalyst for the practice, more fully apply the gifts they bring to the table in order to help the organization live?

Tell the Group One Interesting Thing about Yourself

Last month—ring, ring—a favored client called me on the telephone. The executives who lead her firm had convened an off-site meeting to plan the latter half of the year: a strategy session replete with coffee, croissants, and woodland views. They had secured the services of a professional facilitator to ensure a successful event.

She forwarded me the agenda, pictures of the event, and pictures of the work products.

These confab artifacts told me that the facilitator had served them well. The agenda flowed logically. The participants worked in easy engagement. One picture showed people participating in a dot-voting exercise. One picture showed people drawing a future state for the company on a white board. One picture showed a floor-to-ceiling window covered with Post-It® notes. Flowering trees bordering a small lake appeared in the background, lending the brainstorm a sylvan air.

My client asked if we could run what would in effect be a “post facto” challenge. At the end of the day the participants had engaged in an envisioning exercise. How might we, as an organization, achieve a critical business goal in the next 90 days? The group, fueled by macaroons and a question that went for the jugular, responded with a window’s worth of ideas, one per Post-It note.

What now—now that the executives had generated all these ideas and returned to their day jobs? Which ideas would the organization pursue? Who would pursue them? Had the executives committed to the exercise as something more than a cathartic brainstorm with which to end the off-site meeting on a high note?

She knew that, lacking practice discipline, the executives had perhaps lost a transformative opportunity for advancing its charter. They would not meet in person again for six months.

Let Us Capture That Thought in the Parking Lot

Many organizations benefit from professional facilitation. Large firms employ people who facilitate groups as either a full-time vocation or part-time work, offered as needed. Smaller firms contract with professional facilitators. The International Association of Facilitators (IAF), for example, keeps a roster of certified professionals available for hire.

Professional facilitators have largely pursued their practice from within the human resources (HR) department. Many have an HR background. They often find homes within the organizational development and labor relations groups in HR.

This corporate functional setting tends to make facilitators generalists, by nature. They facilitate strategy sessions with executives. They facilitate workplace disputes. They facilitate large-group envisioning sessions as part of all-hands and off-site events. The diversity of their experiences leavens their practice.

What about facilitating the practice of collaborative innovation? Here, I offer two tasty tidbits on how a professional facilitator might proactively approach an envisioning exercise: (1) keep the end game in mind and (2) blend virtual and physical forums.

Keep the End Game in Mind

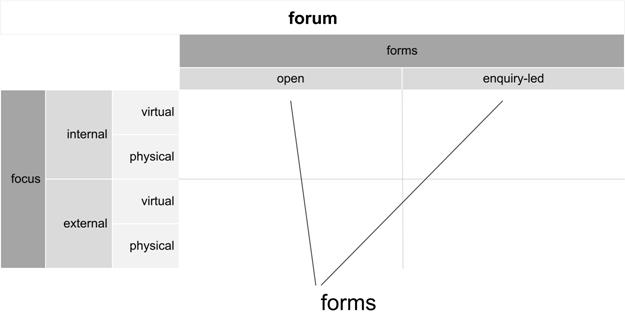

The practice of collaborative innovation takes two forms: open and enquiry led. In the open form of collaborative innovation, people offer insights, perspective, and ideas, with no demand that colleagues act upon their contributions. A contribution may be, for example, a link to an article that they read in the local newspaper. In the enquiry led form, people offer ideas in response to a question posed by a challenge sponsor. The challenge sponsor, often a senior member of the organization, commits to acting upon ideas that people contribute.

Figure 1: the two forms that define the collaborative innovation space

If a sponsor asks you, as a professional facilitator, to help convene a group of people in collaborative innovation, then ask this person in turn whether they wish to pursue the open or enquiry-led form.

Each form has its advantages. One form is not superior to the other. Context matters.

You may want to explore the open form when you sense that the group needs catharsis: an opportunity simply to be heard and to hear one another. Let’s clear the air. Rapid-fire brainstorming works well in this case. As a professional facilitator, you know many ways of helping groups achieve this goal.

You may want to explore the enquiry led form when you sense that the group must take action: a crisis situation, for example, where taking no action would lead to unvarnished calamity. This form demands a greater level of rigor in set-up, execution, and resolution. In the set-up, understanding the sponsor and their desired end state is critical to question formation. In the execution, having a way to help participants assess the ideas by the relevant parameters is critical. In the resolution, assigning ownership and next steps is critical.

These statements on the end game may seem obvious. Yet—and yet—I have over the years received many, many calls from clients seeking a way to transform, post facto, what was facilitated as an open form into an enquiry led form. The group loses a lot of momentum and, at times, goodwill in attempting to make this tardy transition.

Blend Virtual and Physical Forums

Professional facilitators have historically honed their craft by convening groups in person for the simple reason that technologically mature and accessible forms of virtual collaborative innovation did not exist until a few years ago. Long-established, potent approaches to collaboration such as Appreciative Enquiry, Future Search, and The World Café presume in-person convocation.

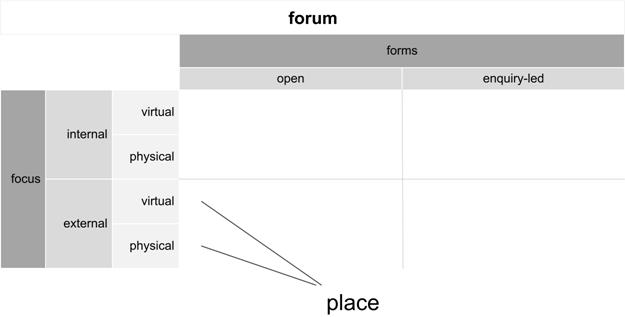

At the risk of stereotyping, I find in my own travels that professional facilitators have not fully explored how they might best blend the virtual forum into the open and enquiry-led forms (figure 2). I share a couple thoughts on this opportunity.

Figure 2: the virtual and in-person place as complementary adjuncts to the internal and external focus

First, virtual forums give you as a professional facilitator a chance to speed the group’s discovery process. In an in-person forum, collaboration does not start until the people you have convened arrive at the venue, obviously.

In the enquiry-led form, for example, you can form and pose the critical question to the group weeks before they convene in person. They have the opportunity to ponder the question more fully. They have the opportunity to craft fully formed ideas in response to the question. They can get a sense of which ideas resonate with the group. They have the opportunity to gain their colleague’s perspective.

In this scenario, introducing the virtual forum frees you to turn what has historically been a discovery process into a resolution process. In the enquiry-led form, the focus in part or in whole turns to helping the group decide which ideas to pursue and in what manner to pursue them.

This acceleration can appeal to sponsors, as they typically want to expedite the transition from thinking about how the group might address a critical business question to the hands-on work of addressing it. The most common question that professional facilitators hear from sponsors is, “How will we handle the ‘next steps’ part of the day?”

What if you could start a session by immediately focusing on next steps?

Parting Thoughts

Knowingly or not, professional facilitators have engaged in the practice of collaborative innovation. I fail to think of a time when I have participated in a professionally facilitated event where the group did not generate insights and ideas through the guided dialogue that drives these sessions.

What has changed? Two things: (1) organizations place higher value on “making innovation part of everyone’s job and responsibility” and (2) the introduction of technologies that enable the virtual forums of collaborative innovation have forced organizations to codify the practice—particularly the enquiry-led form—to a new degree. People are being a lot more explicit about their practice, in other words, because they seek to benefit more from its outcomes.

Today, professional facilitators have the opportunity—if they choose to pursue it—to recast their role from generalist to a catalyst for enabling what is becoming a critical function with a well-defined practice.

About the author

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations big and small navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by developing approaches, creating forums, and structuring engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the process and ideas that result.As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations big and small navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by developing approaches, creating forums, and structuring engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the process and ideas that result.As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Today, Doug works at social innovation leader Spigit, where he consults with clients such as BECU, Estee Lauder Companies, Johnson & Johnson, Ryder System and the U.S. Postal Service. Doug helps them to realize their potential for leadership by applying the practice of collaborative innovation.

Photo: Group of business people from shutterstock.com