What paths along the back end lead to leadership? What paths reinforce the bad habits that the organization seeks to shed as it comes to terms with the new business constructs of the Digital Age?

Now What?

My tyro clients share the following concern with me: What if I throw a party and nobody comes?

That is, what if I sponsor a collaborative innovation challenge and nobody in turn contributes their ideas? The wisdom of the crowd eludes us, absent the crowd.

In my experience, the party goes off without a hitch. The crowd shows up. Everybody has a good time. They make a mental note to RSVP for the next event, which leads to the next challenge: How does the sponsor – and the organization at large – address in a productive, responsible way the many ideas that people contribute, but that the formal organization has no capacity to entertain in the near term? My experience has been that sponsors have the capacity to act upon from 5 to 20 percent of the ideas that people contribute.

In most organizations people equate a promise to consider ideas later – mañana –to “no.”Benign and malign neglect are one in the same to those who authentically engage in collaborative innovation with you.

What might sponsors do at the close of a collaborative innovation challenge to deepen their commitment and increase the likelihood of effecting transformation?

Knowing You, Knowing Me

Two types of organizations wade into the practice of collaborative innovation: those with a culture of top-down decision making and those with a culture of supporting decision making at the places where the work is done.

Circumstances dictate the model. Organizations that work in heavily regulated industries or in complex environments governed by interconnected systems tend to go top down. The cost of something going wrong in this environment, outside the designation of authority, tends to be unacceptably high.

The challenge that top-down organizations, in particular, face, in pursuing the enquiry-led approach to collaborative innovation is that, in designating a sponsor, the challenge team sends a message to the community that someone – ostensibly someone with the necessary authority – will “do something” with the ideas they contribute and that the crowd sources, either in person or virtually. This signal, implicitly or explicitly delivered, causes two problems. First, sponsors are not omnipotent. They, through their authority alone, may not be able to act upon all the ideas, not matter how compelling they may be. Second, this signal, no matter how unintentionally sent, may reinforce the very cultural norms that the organization wishes to diminish through the practice of collaborative innovation.

Edward Deming tells us that we should be open to the possibility that we can make matters worse through our interventions. The practice of collaborative innovation is not above the law in this regard.

Food for Thought on Back End Commitment

Do we throw in the towel? Give up?

No. Organizations thrive in the Digital Age to the extent that they learn how to pose the critical business questions that define their charter and to innovate around those questions together. Organizations that master this part of the practice, using a variety of tools and techniques at their disposal, will find that they can keep pace with and take advantage of the relentless rate of change that the Digital Age imposes on us.

Instead, I recommend that organizations that pursue collaborative innovation challenges make the following commitment at the start of their campaign.

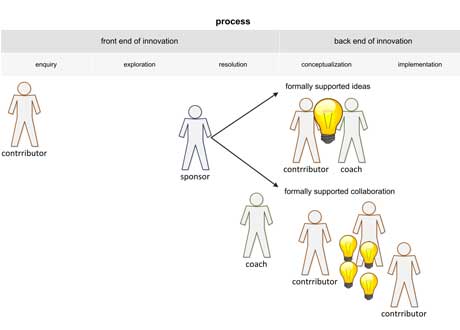

Firstly, for those compelling ideas that the challenge team wishes to advance in the near term, the sponsor agrees to pair the contributor with a senior coach to help them move the idea forward to concept and, potentially, implementation. The senior coach may, in turn, call in the required technical resource – that resource being defined by the nature of the idea and the internal decision-making process. This policy counteracts the signal that contributors have a small, prescribed role in the evolution of their ideas

The Digital Age defines organizational leaders by their ability to in tandem build the business and build their people.

Secondly, for those ideas that the crowd finds compelling, but the challenge teams chooses not to shepherd in the near term, the sponsor commits to convening “collaborative study groups.” The sponsor makes space for blue sky or third horizon thinking.

A collaborative study group consists of people who contribute ideas that show common thematic elements. Envision groups of five to seven people. The group considers seven to ten ideas, in total, as a larger concept.

Here again, the sponsor designates a senior member of the organization to facilitate conversations around the ideas that comprise the theme. How might they explore the idea’s potential? What commitment can they make to one another? Can they develop a proposal for action? Can they, together, tackle the challenges that come with advocating effectively for the theme?

Figure 1 depicts the two threads of commitment: formal support for pursuing certain ideas and formal support to make space for collaborative study groups around common themes to be pursued for the longer term.

Figure 1: sponsorship of idea and collaboration groups as the near-term commitment

Some may view the idea of facilitating collaborative study groups as a rather tepid response to a hard constraint: the maximum capacity that the organization has to entertain new ideas.

I disagree. I have seen organizations extend what was once viewed as the collective, maximum capacity through this approach. Often, the groups in their explorations uncover unused or inefficiently used resources that they can press into service. At times, these groups, through their entrepreneurialism, catch the attention of a senior leader who enables them to reframe the problem by providing extra resource. The amount of authentic growth that occurs in this organic fashion, outside the balance sheet chicanery of mergers and acquisitions, would surprise most people.

To engage in the practice of collaborative innovation is to be in the business of optimism, bolstered by a commitment to rigorous enquiry of the possibilities that abound.

Parting Thoughts

Collaborative innovation transforms an organization to the extent that the practice creates a path to where the organization wants to go in the Digital Age. A powerful practice encourages collaborative problem solving. What question is worth pursuing? How might we explore our answers?

At the back end of innovation, the place where people test their ideas and the hypotheses underlying them, savvy challenge sponsors focus on coaching their top contributors in advancing their ideas. Savvy sponsors create their version of the collaborative study group for the people who contributed the next tier of ideas.

The Digital Age is disruptive largely because it accelerates decision making beyond what traditional organizational structures can handle. The Digital Age to this end demands that organizations place a premium on leadership: leadership at the sponsor level and leadership at the contributor level. Back end commitment clears a space for guided experimentation and entrepreneurialism to occur.

The practice serves as a litmus test for who will thrive in the Digital Age. Will you pass?

About the author

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations big and small navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by developing approaches, creating forums, and structuring engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the process and ideas that result.As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations big and small navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by developing approaches, creating forums, and structuring engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the process and ideas that result.As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Today, Doug works at social innovation leader Spigit, where he consults with clients such as BECU, Estee Lauder Companies, Johnson & Johnson, Ryder System and the U.S. Postal Service. Doug helps them to realize their potential for leadership by applying the practice of collaborative innovation.

Photo: Freedom business woman on a swing from shutterstock.com