This past fall our columnist the innovation architect Doug Collins began the tale of how the Dirty Maple Flooring Company came to embrace the Digital Age through the practice of collaborative innovation. The latest episode appears below.

The approach to challenge resolution described in this episode is covered in more detail here.

A Brief Pause to Reflect

Leadership is navigation.

All Quiet along the Sheboygan River

“So, it’s settled?” Harry asked.

“Yes,” Frankie replied. “I am satisfied.”

Harry turned to Charlie. “What about you?”

“Yes, me, too. I’m pleased with the outcome,” Charlie replied.

Harry looked across the lawn, newly green in the spring, which ran to the dog leg turn of the Sheboygan River which defined the northern edge of his land. The quiet here led to more open, flowing conversations than his office at Dirty Maple could sustain. It was a good place to mull the future as the river flowed to Lake Michigan.

“What’s next?” asked Ivete.

“I was wondering the same thing,” Harry said.

Flashback to the Challenge Resolution Session

Two days earlier on Thursday, Charlie, Frankie, and the first challenge team for the Idea Mill Program—Carlos, Ivete, and Benyamin—had convened in the barn on Harry’s property which he had converted to recreational space for his family and, at times, colleagues.

The first challenge, “How might we take greater ownership of the near-term change in client demand in the markets we serve?” had generated 114 ideas from a community of a couple thousand people, worldwide.

Of the 114 ideas, the community, through their collaboration with the contributors and one another, had narrowed the pool to 12 which appeared to hold the most promise.

Frankie, Charlie, Carlos, Ivete, and Benyamin met to make further meaning of the 12. Which should Dirty Maple pursue in the short term? In the long term? Not at all?

To help structure the session, Charlie had asked the team to score each idea by criteria established by Everett Rogers, whose research explored why some ideas proliferate and others do not: relative advantage, cost of adoption, complexity, trialability, and observability.

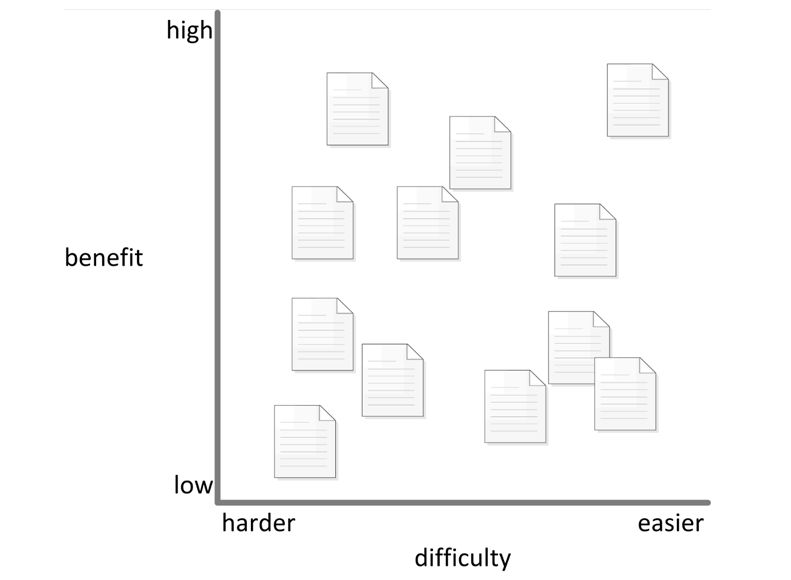

The scoring enabled Charlie to juxtapose the ideas on an XY-grid, with relative advantage on the X-axis and degree of difficulty on the Y-axis. Degree of difficulty equaled the sum of the average of the last four of Rogers’ criteria (figure 1). Charlie posted the grid on the wide expanse of the south wall of the barn.

Figure 1: the 12 ideas, juxtaposed on the XY-grid

Charlie, embracing his inner facilitator, issued each team member 24 sticky dots: six dots in green, yellow, red, and blue. Green meant “pursue the idea now.” Yellow meant “pursue the idea later.” Red meant “do not pursue the idea.” Blue meant “we are already pursuing the idea.” Each team member had half the number of dots by color as there were ideas: an exercise in optimization.

“You would think we would know our blues,” Frankie observed.

“Yes, indeed—surprising, that one,” Charlie said. One of the immediate benefits of the challenge was that the collaboration surfaced a half dozen cases where Dirty Maple’s right hand was unaware of the left’s activities, relative to developing and socializing sales forecasts across the enterprise. Frankie had already started outreach to rationalize processes across the regions.

This finding on the “blues” reminded Charlie of one of the core precepts of his time with Dirty Maple’s Lean Program Office: there are always new problems to solve. Frankie estimated that reducing process inconsistencies would, alone, get the challenge team a quarter of the way towards their business goals for improving forecast accuracy.

Inconsistency leads to inefficiency. Charlie found that the virtual form of collaborative innovation did a good job of surfacing the former by way of improving the latter.

Fuzzy Front End Tofu

“Shouldn’t we be calculating ROI as part of this exercise?” Benyamin asked as he thoughtfully depleted his supply of stick dots.

“No, not yet,” Charlie said as he sat on the futon that the Lundstroms had set against the east wall of the barn. “These ideas, as fully formed as they may seem, remain in their formative state on the fuzzy front end. We don’t know yet how we will pursue them, who will do so, and the pace at which they’ll be able to go. ROI is a time-based measure—present value and such.”

The room grew quiet. Charlie heard the Lundstroms’ German shepherd barking outside the barn.

“You’re making the make-up of the back end team a factor?” Ivete asked.

“Yes, definitely,” Charlie replied, “that’s reality. An idea, pursued by one person or team, will yield much different results in the hands of another person or team.”

“I feel at times as if I am walking through tofu,” Benyamin said.

“Fuzzy tofu,” Ivete added.

“Fuzzy front end tofu,” Frankie added.

“Yes,” Charlie said, wondering if lunch had arrived. “I come to think that the practice of collaborative innovation is a crucible in which leadership is formed. It forces you to navigate ambiguity, along with a healthy amount of skepticism from all quarters.”

Lunch Time

“Those three ideas on forecasting sales of new flooring products as part of our go-to-market process seem like variations on a theme,” Frankie said, munching on a mett wurst, a Wisconsin lunchtime staple.

“Well, let’s group them together, Carlos said. “Any reason why we can’t treat them as a larger concept?”

“I don’t see why not,” Charlie said, letting a mett wurst laden belch. “A lot of these ideas, taken as a whole, seem like pieces of a puzzle.”

The team continued working. The shade from the beech trees that bordered the barn door swept from the west to the east.

What’s Next?

“What’s next?” Harry repeated.

“Well,” Frankie said, “of the 12 ideas, we think three are worth pursuing in the near term as a larger, move-the-needle concept. I think they get us 75% towards our goals. Four more we agreed were yellow—longer term improvements we can work on now with an eye towards rolling out in the next fiscal year. We’ll tie them to the Duroboard launch in February.”

“I see—sounds promising,” Harry said. “And you, Charlie, what’s next?”

“I’m glad you asked, Harry,” Charlie said. “What’s your calendar look like Monday?”

“Why?” Harry asked.

“It’s time to talk about making space – physical space for our innovators to pursue their ideas.”

Harry nodded. “Okay—we can find time.” He watched his son and daughter—both teenagers now—cast their lines in the ripple pools that formed along their side of the river.

By Doug Collins

About the author

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations such as The Estee Lauder Companies, Jarden Corporation, Johnson & Johnson, The Procter & Gamble Company, and Ryder System navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation. Doug develops approaches, creates forums, and structures engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the ideas and to the collaboration that result.

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations such as The Estee Lauder Companies, Jarden Corporation, Johnson & Johnson, The Procter & Gamble Company, and Ryder System navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation. Doug develops approaches, creates forums, and structures engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the ideas and to the collaboration that result.

As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL). Today, Doug works as senior practice leader at social innovation company Mindjet, where he consults with a range of clients. He focuses on helping them realize their potential for leadership by applying the practice of collaborative innovation.

Photo : Red Barn by Shutterstock.com