By: Arnaud Groff / Jean François Lacoste-Bourgeacq

In last week’s IM article we looked beyond national innovation metrics at how in the French system innovation is stifled by education, culture and systemic factors. Can we recalibrate innovation through national policy? This weeks concluding article looks at how the policy makers should be redirecting their efforts beyond traditional measures.

At the territory level, an initiative such as the “27th region” has recently appeared. This is a public innovative agency whose goal is to help the French regions to change their policy making methods and prepare them to enter a more workable world. Its action is based primarily on a greater involvement of citizens in their choice and is in line with the need to create more relations between territories, management and citizens.

In education, some major French colleges have realized that they had to use every incentive to integrate young people from different backgrounds to those they traditionally welcome. In addition, more and more young French have a positive view of entrepreneurship. In 2009, a survey by the institute OpinionWay indicates that over 50% of young people said they were tempted by entrepreneurial jobs. These young people believe that the ideal company has to carry the values of innovation, team spirit and be at a scale where each employee can be heard.

But the French education system has yet to promote:

- The right to be wrong

Young people believe that the ideal company has to carry the values of innovation, team spirit and be at a scale where each employee can be heard.

- Learning through experimentation

- Science and Philosophy as the foundation of thought

- Learning to build tolerance

- Access to art and culture in general

- Openness to other cultures

We are moving away gradually from the bureaucratic centralism of major innovation programs. More efficient structures are building robust innovation capabilities in some specific parts of the French territory by dynamically balancing technological supply and demand between academic research labs and private companies. Minatec is an excellent example. This is a campus of innovation in micro and nanotechnology located in Grenoble. The activities are based upon a matrix that cross science and cutting edge technologies in three directions:

- Prospective and strategy

- Program Support

- Technology utilization

In each “lab” there is a matrix organization crossing “business” platforms and projects. This “matchmaking” between academic, private and industrial players, comes from a robust network environment: innovators ecosystem nested in an appropriate innovation ecosystem.

Other improvements are on their way, including those relating to better organization and professionalization of research utilization structures. Initiatives such as “La Cantine” in Paris stimulate innovation bubbling through creative spaces where informal exchanges can be set up, favoring the emergence of communities of innovators.

These examples show a different way to look at innovation in terms of systemic change, changes that promote new activities and actions.

These examples show a different way to look at innovation in terms of systemic change, changes that promote new activities and actions. An international comparison table in 2011 and going forward should not rely on past measures of innovation. We need to take into account how we change behavior and how we enable people to express their aspirations.

Permitting and encouraging risk taking, reorienting or learning systems to experimentation, building tolerance, being open to cultures, having access to creative culture and art. These are the basis of a new comparative innovation table.

The approach that we have been discussing here could be used to analyze the situation of other countries as well. What is specific to this approach is less its simplicity than its scope.

Instead of starting from a one size fits all global innovation index supposedly designed to compare countries innovation performances, we start from the country culture and specific environment.

Then we break down into large building blocks that would give a clearer vision about how innovation is working country-wise. Innovation must create value. Even though we are in a global economy, what is considered as valuable in a country may not be valuable for other countries.

We have then to select the most appropriate criteria to play with. The first one is closely related to people, culture and history. This is what we have named the “Nation” criteria. A centralizing administration has been key to France in the past, while risk taking for wealth accumulation and centering on personal material advancement are part of the US culture. These two extreme cultural features are not giving anymore advantage when it comes to how we innovate, in an era emphasizing interdependence, sustainable development and broad human welfare. Nations balancing them properly are better equipped. This is the case of Nations like Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Singapore …

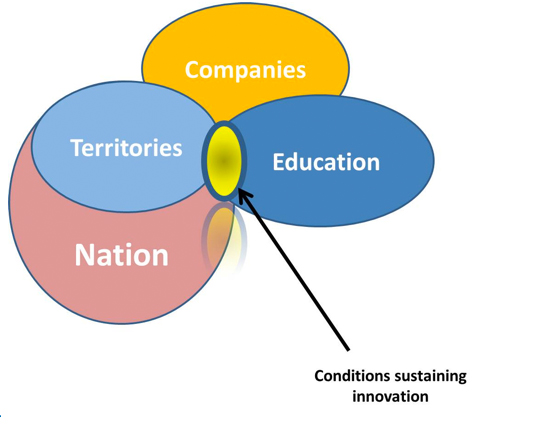

Nation innovation capabilities lie on two key thoughts about innovation:

a) Innovation must be seen as a result of the activity of ecosystems closely interwoven in order to ensure their sustainability.

b) These ecosystems are going to benefit from levers located mainly at four levels: nation, territory, education, companies.

By studying the key factors involved in these four levels, we will be able to assess more specific areas for improvement of the capabilities to innovate. The other advantage of our approach is that it can make people aware that a company has also a societal and not only economical role.

Finally, it shows what interactions have a role in values creation that nurtures innovation (Figure 1). Our method of evaluation therefore takes into account how fruitful the environment that fuels the innovation engine is in a given territory. It lies mostly on socio-structural and geo-political parameters.

Creation and stimulation of innovation ecosystems have become instrumental to nation competitiveness. These innovation ecosystems can only exist in fertile territory boosting the development of innovators ecosystems. A question mark, which is then arising, is related to the capability of education systems to empower an innovator mindset. Risk taking, creativity and collaborative spirit are part of this innovators’ mindset. A lot of countries are understanding that education is at the base of innovation and creativity and that leaving an opened door to creativity and innovation is primordial. India is being inundated with a monsoon of innovations. Companies have no trouble finding the talent and entrepreneurial energy for innovations to drive growth. This drive is missing in a lot of European countries where people take their work and lifestyle for granted.

In 2010, studies confirmed that creativity in America was on decline, especially for America’s youth. While the rest of the world is heading in a non-standartized curicula and non-nationalized testing, America is heading in exactly the opposite direction. Yet, the so-called creativity crisis in America fails to account for a singularly astounding fact which is that at the same time that creativity scores are falling, America’s youth have been responsible for the creation of some of the world’s most innovative and creative technological start-ups.

Figure 1: the four cornerstones of national innovation performances

Some explanations may come from the way US education promote collaborative work, and from the fact that interrelated professional and personal networks are actively designed to support and connect business initiatives.

This is a good example of what a systemic approach can show about innovation. Our thoughts here have to be considered as a preliminary material. No doubt that they need some enrichment by the innovation experts community.

By Jean-François Lacoste-Bourgeacq and Arnaud Groff

Acknowledgments: we are grateful to Dr Luce Basetti who has challenged us on some ideas of this article.

About the authors:

Jean-François Lacoste-Bourgeacq has 25 years of business experience in innovation management and utilization. Adding value to and through innovation is Jean François’s core expertise. He has published a number of scientific papers as well as two books on “Agile Innovation” and innovation risk intelligence. (AFNOR editions, 2007, 2009.). He is the founder of Qiventiv Systems, a company which is offering a full range of services and tools to create and boost innovation ecosystems, from innovation processing to open innovation. This company is working on new collaborative innovation tools concepts. Jean François is part of the experts committee working at the European level on innovation management guidelines.

Jean-François Lacoste-Bourgeacq has 25 years of business experience in innovation management and utilization. Adding value to and through innovation is Jean François’s core expertise. He has published a number of scientific papers as well as two books on “Agile Innovation” and innovation risk intelligence. (AFNOR editions, 2007, 2009.). He is the founder of Qiventiv Systems, a company which is offering a full range of services and tools to create and boost innovation ecosystems, from innovation processing to open innovation. This company is working on new collaborative innovation tools concepts. Jean François is part of the experts committee working at the European level on innovation management guidelines.

Arnaud Groff holds a PhD in innovation and creativity management from the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts et Métiers (ENSAM Paris). He also holds a MS in new product design and engineering from ENSAM. He is an expert in industrial innovation and strategic management of creativity. He founded his own company, Inovatech 3V, in 2004. Today, he and his experts support many French companies and institutions to innovate more effectively by managing in a better way innovation and creativity in order to create sustainable value. He has written different books on business and creativity management (100 questions about innovation management in 2009 published by AFNOR, recently, 100 questions about creativity, by AFNOR publisher. The toolbox of creativity will be published end of 2011 January by Dunod publisher).

Arnaud Groff holds a PhD in innovation and creativity management from the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts et Métiers (ENSAM Paris). He also holds a MS in new product design and engineering from ENSAM. He is an expert in industrial innovation and strategic management of creativity. He founded his own company, Inovatech 3V, in 2004. Today, he and his experts support many French companies and institutions to innovate more effectively by managing in a better way innovation and creativity in order to create sustainable value. He has written different books on business and creativity management (100 questions about innovation management in 2009 published by AFNOR, recently, 100 questions about creativity, by AFNOR publisher. The toolbox of creativity will be published end of 2011 January by Dunod publisher).