By: Doug Collins

The practice of collaborative innovation starts with observation: the discipline to see and grasp the nature of the work, the end user’s environment, or the world at large. In this article innovation architect Doug Collins explores how people who lead their organization’s collaborative innovation practice can reinforce community members’ observational skills.

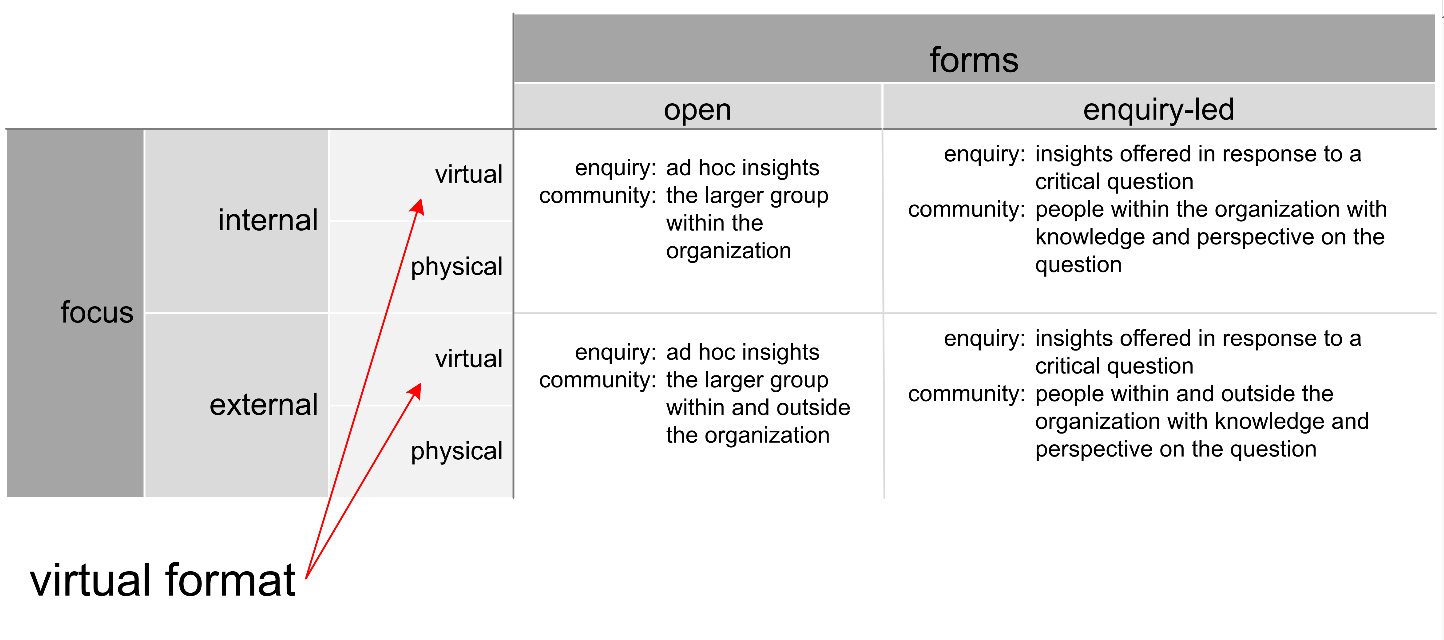

Organizations deploy the virtual format for the practice of collaborative innovation at a fast clip today (figure 1). People watch the allied capabilities of social media and gamification proliferate in the consumer world. They experiment with applying the same approaches to the virtual format, both internally with associates and externally with end users.

Figure 1: the virtual format in the context of the collaborative innovation space

The virtual format offers advantages over the physical complement, beyond the benefits that the recent technological advances bring. Organizations can engage geographically dispersed community members in co-innovation and co-creation: people who might otherwise not have a chance to participate. The virtual format allows community members to continue dialogue and trains of thought after in-person brainstorms and other means of in-person engagement come to a close.

At the same time, the fascination with the technologies that enable virtual collaboration, along with the relative ease in which organizations can deploy them, can cause practitioners to overemphasize digital engagement at the expense of the in-person, on-site observational techniques that ground the practice.

In this article I explore ways that practitioners can balance the two, the virtual and the physical, by treating observation as a foundational skill.

Seeing the whole

The virtuous circle of observation and reflection that leads to insights, ideas, and innovation holds a well-established, respected place in the practice of collaborative innovation in all its forms.

People who practice lean talk of “taking the Gemba walk.” The lean practitioner starts at the end user’s site (the source of the demand for their organization’s offer) and literally walks back through their supply chain to the vendor organizations in order to identify opportunities to remove waste in the processes and to identify new opportunities to provide more value. Lean practitioners create value stream maps by way of capturing their observations.

People that pursue design thinking, as evolved by groups such as IDEO, physically descend upon an end user’s site for days to weeks in order to observe and gain intimate, first-hand knowledge about the nature of the problem to solve. They dismiss understanding problems by proxy.

People that embrace Clayton Christensen’s view that firms succeed to the extent that they understand and innovate on the jobs their clients want to do, such as Tony Ulwick and his group at Strategyn, spend extended periods of time with end users. They cannot comprehend the jobs the clients assess as worth doing from behind their desks.

All forms of the practice of collaborative innovation demand that practitioners become ethnographers and anthropologists…

All forms of the practice of collaborative innovation demand that practitioners become ethnographers and anthropologists so that they can develop insights into the true nature of the problem to be solved or the opportunity to be exploited. Absent this commitment and this discipline, the virtual format of the practice degenerates into the electronic suggestion box. Garbage in. Garbage out.

The people who lead their organization’s collaborative innovation practice can take the following steps to reinforce the important role that observation plays.

Host Gemba Walks

Campaign teams, when starting a new challenge with a sponsor and community, focus on the “three C’s”: the critical question, the community engagement model, and the commitment that the sponsor seeks from the community—and vice versa. One commitment that the campaign team and the sponsor should make to the community is to provide an opportunity for community members to take a gemba walk that relates to the critical question.

For example, suppose the critical question addresses how the organization might improve the customer’s experience. What opportunities do community members have to observe the customer experiencing an engagement with the organization? What opportunities do community members have to observe the client’s environment, overall? Can they see the customer being served?

One client of mine pursues a variation of the gemba walk by incorporating “trend tours” into her collaborative innovation program. On a regular basis she invites and leads community members through a part of their headquarters city, immersing them in the latest developments in their space, which, in this case, they can see unfolding on the street. These tours open the organization’s use of the virtual format.

Inviting a diverse group of community members who do not ordinarily get to observe the client can yield insightful observations that may lead to compelling ideas. Defer inviting the usual suspects—the people who believe they “own” the relationship with the client—to the gemba walk. Seek fresh eyes.

You miss a step when you do not bake in an in-person review of the end user environment as part of your collaborative innovation campaign. Refer to Jim Womack’s book on this topic, Gemba Walks. You do not have to share his interest in lean to gain insights into the power of observation that he conveys.

Bake observation into the virtual format

Chris Miller and his group at Innovation Focus developed the Hunting for Hunting Grounds approach to support observational enquiry. The Hunting Grounds approach has participants capture their insights in the format of observation, implication, and application: what do I see, what does it mean, and what do I do next to learn more.

I advise my clients to apply this approach in the virtual format as part of asking community members to capture their insights (figure 2).

Figure 2: idea capture format

Doing so benefits the campaign in two ways. First, capturing observations forces community members to reflect on what they are seeing in the end user’s environment. They move from responding to a virtual suggestion box to becoming more thoughtful in their own practice. Organizations become more innovative to the extent that the people who work there hone their observational skills. Second, capturing observations serves as valuable food for thought for fellow community members. Do they see the same problems in the end user’s environment? Do their observations lead them to offer similar opportunities to improve (i.e., the “applications” piece)? Organizations reduce the value of the virtual format when they fail to ask community members to commit to providing observations.

Incorporate observational rewards into the incentive structure

Campaign teams have discretion in terms of the incentive structure they can offer community members who engage in collaborative innovation. They can use their freedom to reinforce the value of observation.

For example, campaign teams can offer unlined Moleskin notebooks to community members who participate in a challenge at some minimal level. The common varieties can be acquired at quantity for under USD 10 per notebook. Creative campaign teams can personalize the incentives with logos or the recipient’s name. They can incorporate the Hunting Grounds template.

Moving up a step, campaign teams can offer the opportunity to spend time with the end users. Community members may value the chance to practice the observational techniques and engage the end users, particularly when doing so falls outside the confines of their daily work. The practice of collaborative innovation in all its forms is, in fact, a practice. Effective campaign teams find ways to help their community members hone their skills.

Moving up a step further, campaign teams can offer community members the chance to practice their observational skills with the masters at firms such as Strategyn, Innovation Focus, and IDEO. They regularly offer seminars to the public, outside their consulting engagements.

Given the importance that organizations place on innovation, campaign teams that help their community members hone their observational skills find that their efforts align with the learning and growth objectives for the group at large.

Parting Thoughts

Innovative people make innovative organizations. One commitment that the campaign team makes to the organization at large as they lead the practice of collaborative innovation is, challenge by challenge, to help each community member improve their individual competencies.

Start by helping people build their observational skills. Observation drives the insights that drive the experimentation that in turn opens the door to meaningful innovation.

By Doug Collins

About the Author:

Doug Collins is an Innovation Architect who has specialized in the fuzzy front end of innovation for over 15 years. He has served a variety of roles in helping organizations navigate the fuzzy front end by creating forums, venues, and approaches where the group can convene to explore the critical question.

Doug Collins is an Innovation Architect who has specialized in the fuzzy front end of innovation for over 15 years. He has served a variety of roles in helping organizations navigate the fuzzy front end by creating forums, venues, and approaches where the group can convene to explore the critical question.

As an author, Doug explores the critical questions relating to innovation in his book Innovation Architecture, Practical Approaches to Theory, Collaboration and Implementation. The book offers a blueprint for collaborative innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management.