By: Doug Collins

The Digital Age, like a hoochie mama navigating a Saturday night in heels, bares all. Citizens, regulators, employees, and investors see in real time how well organizations manage their supply chains. Transparency by nature raises the bar.

Introduction

Supply chain managers have as a result embraced sustainability as a way to reduce risking their brand’s equity and as a way to profit. A resource conserved is a dollar saved.

In this article innovation architect Doug Collins explores how a product supply group might apply the blueprint for collaborative innovation to advance their sustainability charter.

Harbor Side

Airlines give their passengers de facto tours of arrival cities as the plane descends. Each city puts on a show. The Manhattan skyline stands for inspection for people landing at La Guardia or JFK. The transecting geometry of the Washington Monument, the Capitol, and the White House greets people landing at Reagan National.

Landing at Boston’s Logan Airport catches my attention. One sees first the coat-hook finger of land with Cape Cod serving as the nail. One sees later the wood clapboard houses that ring the harbor, steps from the bay. I wonder, always, how the residents weather the storms. An optimist, I try not to dwell on what these towns will look like ten years from now as the sea rises.

Do row boats replace lawn mowers?

Our choices have a clear, collective effect on others in our connected, digital world. Do we burn coal? Do we capture the wind? Do we drive the car? Do we pedal to work? The people who see Boston Harbor from their kitchen windows have a horse in our race.

People who work in product and service supply command enormous resources. They make decisions that materially affect the long-term sustainability of the planet. Their vocation has a powerful component of stewardship which, today, they cannot ignore.

In this article I apply the blueprint for collaborative innovation to a supply chain scenario. How might a supply chain leader apply collaborative innovation to explore the possibilities around achieving greater levels of sustainability? I reference PWC’s Global Supply Chain Survey 2013.

Intent to Forum to Process

The blueprint for collaborative innovation helps people apply the practice of collaborative innovation to their goals by convening a community on the critical questions facing the organization. Figure 1 shows the steps, one, two, and three. In this article I focus on the set-up: intent and forum.

Figure 1: the blueprint–moving from intent to forum to process

Many ways exist to depict intent. Examples such as the Balanced Scorecard, the A3, and the SWOT diagram work because they share the following traits: they are visual, enabling people to grasp the scenario, and they fit on a page, enabling people to “see the whole.”

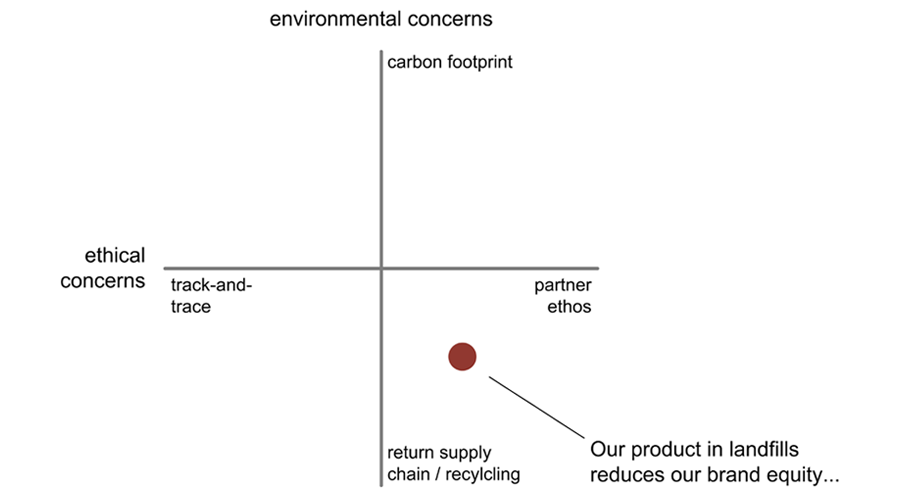

Using the PWC survey as a reference for our fictional supply chain organization—one concerned with sustainability—a depiction of intent might appear as follows (figure 2):

Figure 2: mapping intent by using PWC’s Global Supply Chain Survey

The four-quadrant grid format is effective because the visual gives people license to play with various trade-offs or permutations of intent. Try a couple versions to see which comes closest to how you perceive your scenarios.

Let us say that, of late, people have been tweeting pictures of the organization’s products in landfills. The images damage the brand’s equity and the organization’s expressed support for environmental causes. The organization, in more fully realizing its potential for leadership, commits to achieving greater levels of sustainability.

The supply chain group, by extension, decides to focus its energies on the second quadrant: re-envisioning supply chain partner engagement in order to begin to support the complete round tripping of product from fulfillment to return to recycling (figure 3).

Figure 3: choosing a focus, relative to intent…

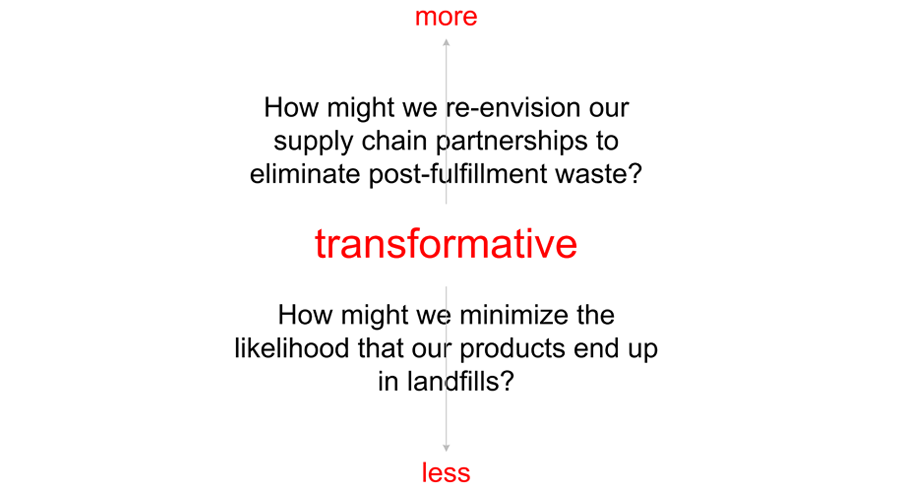

The supply chain leadership group, serving as the sponsors of the collaborative innovation challenge, convenes to consider what level of transformation they seek in posing the associated, critical question to the community, which they identify in the forum section. The group has infinite discretion in couching the question, as they have in depicting intent. Figure 4 shows one example of how the phrasing of the question opens the door more widely to soliciting more transformative ideas from the community.

Figure 4: forming the critical question

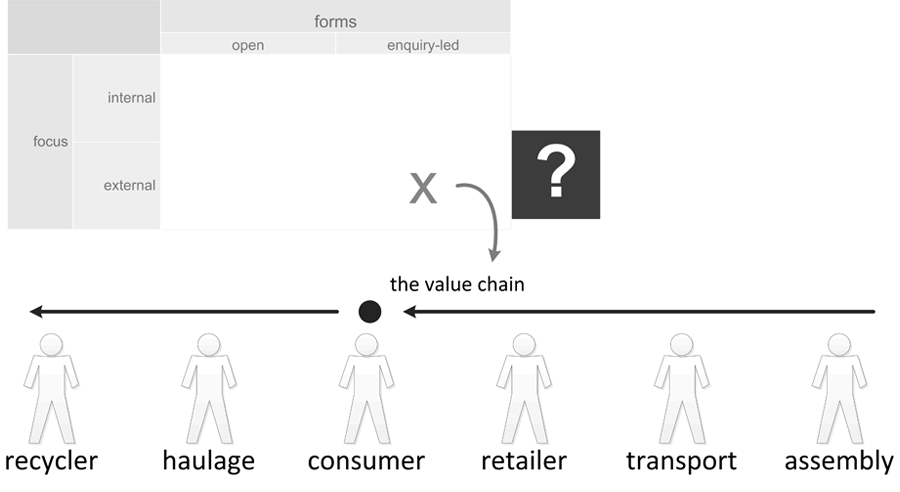

The supply chain leadership group next considers the forum: who to invite to convene on the critical question. Here, they make a critical decision: they decide to pose the critical question externally, given that many stakeholders who participate in the value chain work outside the firm—a natural outcome of the group’s outsourcing strategy (figure 5).

Figure 5: forum—using the value chain associated with the question to identify the community

With these decisions made, the supply chain leadership group can next work out the mechanics of process (figure 6). My one observation here is that the process discussion will very much be a conversation around winners and losers. One stakeholder’s “waste” in this scenario may very well be another stakeholder’s source of revenue. Having a frank and open conversation along these lines will be key to forming an engaged, productive community.

Figure 6: process

Parting Thoughts

Forty-two percent of the supply chain organizations that PWC surveyed for their 2013 study said that sustainability was highly important to them. This number seems low to me, given how far we have trekked into the world of Digital Age transparency. This number, too, suggests to me that leaders of supply chain organizations have enormous, untapped opportunities to pursue greater levels of sustainability, whether for altruistic or economic reasons.

The practice of collaborative innovation is particularly well suited to this pursuit. Making real headway on sustainability requires leaders to convene the large community of people who are involved in provisioning the supply chain. Pursuing sustainability successfully means, as well, identifying and implementing a combination of big, game changing ideas and small, incremental improvements. The innovation community is in the best position to identify both possibilities.

The actuaries will tell us the cost of putting Boston Harbor homes on stilts. The supply chain managers will play a big role in deciding whether the owners need stilts.

About the author

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations big and small navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by developing approaches, creating forums, and structuring engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the process and ideas that result.As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations big and small navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by developing approaches, creating forums, and structuring engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the process and ideas that result.As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Today, Doug works at social innovation leader Spigit, where he consults with clients such as BECU, Estee Lauder Companies, Johnson & Johnson, Ryder System and the U.S. Postal Service. Doug helps them to realize their potential for leadership by applying the practice of collaborative innovation.

Photo: Aerial views of Boston from shutterstock.com