By: Langdon Morris

In this chapter excerpt from The Innovation Formula Langdon Morris explains how to use a map to help you locate your company in the market, to see clearly how it compares with the competition, and then to use this assessment to chart a future path toward success. The goal is to find the very best high reward, low-risk ideas that will change the market, amplify your profits, increase your relevance, and sustain your organization’s viability over the long term.

Most of the forces of change that we described in the previous chapter are probably working against your business, in the sense that in their brutally evil and mercilessly conspiratorial way, they are plotting to bring deep and enduring change to the market, to your market, and to make your current products and services obsolete. They do so without regret or remorse.

In response, you are obliged to innovate.

And in the pursuit of innovation, of course, you will be obliged to engage in taking risk.

Yes, one of the most significant challenges that every small business leader faces is that even when you’re ready and willing to innovate you are immediately confronted with the enormous, elephant-sized issue of figuring out where to invest your precious time and resources. If you’re not hanging around Stanford where hoards of super-smart grad students are cooking up the next HP, Yahoo, Google, or Cisco, where do you find the really great ideas?

Developing or finding the ideas, choosing the best ones, and managing their growth and development through to completion are vital innovation management tasks that we’ll explore in the next chapters. The goal, of course, is to find the very best high reward, low-risk ideas that will change the market, amplify your profits, increase your relevance, and sustain your organization’s viability over the long term.

In broad terms, we know that great ideas often come from one of these four sources, and from combinations of them: customers; suppliers and partners; your own organization; and new technology. Shortly we’ll look critically at each of these four areas, but first we need to frame the problem more precisely by looking at your business as a whole, its strengths and weaknesses, and its position in the marketplace relative to the competitors.

Mapping Your Place in the Market

The first perspective we want to develop to assess your business is to look at its business model. A business model is a description of how a business makes money, which means it might be a very simple thing:

- We make a product; then someone buys it.

- We offer a service; then someone buys it.

Chances are, though, that it’s not really that simple at all. Why do people choose to buy? What’s the value proposition that attracts them? What are the best features that make a difference? What are the strengths and weaknesses in comparison with competitors? What goes into determining the price of the product or service, and in which directions are market prices trending?

Our goal here is to locate your business in the market, to see clearly how it compares with the competition, and then to use this assessment to chart a future path toward success. Hence, we want to address these questions:

Our goal here is to locate your business in the market, to see clearly how it compares with the competition, and then to use this assessment to chart a future path toward success.

- Where are we today, where are our competitors, and in which direction lies the future of our industry?

- Which business models will be successful in the future?

- And thus in which direction(s) should we target our innovation efforts?

Rather than just using descriptive language to explain this it’s very helpful to visualize the market, to map it.

We’ll start with a matrix. Label the horizontal axis “market size.” Moving from left to right means reaching more customers, which thus implies the possibility of decreasing prices as volume increases.

Hence, the business model intent of all large scale retailers is to move progressively to the right, toward ever larger chunks of the market.

Mass market vs. customization

“Lower prices every day” is not a Wal-Mart advertising slogan by accident, but a central element of the company’s branding and value proposition. Hence, the lower right hand corner of the matrix designates the largest mass market, the one with the lowest prices and the most standardization. This is high volume market, the mass of the mass market.

In the USA there’s a company called “The Dollar Store” that occupies that spot. Everything in the store costs, predictably, $1, and the lure is the pricing, as it’s obvious to everyone that this is not the place to be looking for high quality. In fact, the dollar store business model can exist only because of super-high volume manufacturing in massive, highly automated, digitally-controlled factories that crank out impressive (or appalling) volumes of plastics.

The vertical axis is labeled “customization” (or if you prefer,“differentiation”). Moving from bottom toward the top means that the customization and differentiation of the product or service is increasing, which is of course precisely the opposite of the Dollar Store. Therefore, the upper left corner is where you’ll find the exclusive products that only the richest people in the world can buy. Private yachts and jets, Picasso and Van Gogh paintings, mountaintop estates, and private islands.

Conversely, the lower left corner of the matrix would have to be considered as the ultimate Dead Zone. This is the place you don’t want to be, because if there were such a possibility as high prices with no customization, this is where you would find it. No business leader would intentionally choose for their firm to occupy this spot.

What we’ve done is that by defining these two axes and thinking about the position of any individual firm, we’ve created a map that enables us to determine our relative place in the market and to think productively the behavior of our competition, which will of course then to help us plot our future course, and then to target the innovations that are likely to be the most strategically valuable.

The changing face of American retail

As an example of how we can use the model, let’s take the hypothetical example of Sears, the formerly huge American retail company, which was at one time the single most dominant American retailer and a tremendously innovative company that grew to enormous size and exceptional influence. The company’s massive catalog was a treasured item, a compendium of everything that was great about capitalism.

The company prospered by offering great value, and its offers were very specifically targeted at the core of the market, and very large numbers of customers found it very appealing to shop at Sears.

Both as a matter of its business design and its marketing, it strived to be the iconic American retailer. Headquartered in the center of the country, in Chicago, the company exuded confidence and reliably produced handsome profits for many years.

At that time Sears had a much smaller rival, but within 20 years their roles had reversed and the rival, Wal-Mart, had far surpassed Sears. Wal-Mart’s approach was to out-innovate Sears, and while Sears suffered significant declines in its business, Wal-Mart grew very fast, both in the US and then throughout the world.

The market map of 2000 shows that the overall size of the market has grown significantly, which reflects a normal process of economic growth. The map also mentions a key factor, which is that overall customer expectations changed from 1980, and parts of the market that were quite viable in 1980 have been overtaken by the dead zone by 2000. Sears, which stayed resolutely where it was in its core, and did not appear to even be trying to innovate its business, was simply swallowed up by the staying the same.

Changing customer expectations put it solidly in the expanding Dead Zone.

Wal-Mart, in contrast, has consistently demonstrated the qualities necessary for continued success. By developing new innovations in its supply chain, product designs, and in fact across the entire scope of its business model, it succeeded in moving its business model both upward, with higher quality products, and to the right, with progressively lower prices.

(It should be noted that Wal-mart’s employment policies remain controversial, and one can argue that its success is based in part on a practice of under-paying its employees by manipulating the labor laws of the US. For the purposes of this discussion we leave this important issue aside, but it’s important to recognize the ethical problems associated with this practice, and to notice the likelihood that future changes in its business model may be forthcoming in the near future as a result.)

Wal-Mart, and another successful business model innovator Ikea, both continue to aspire to move both up, toward more customization, and to the right, toward ever lower prices. And so do all of their competitors. Including, of course, Amazon.

The way things are going it’s not hard to imagine that by 2020 Sears will have been buried in the Dead Zone, bankrupt and gone. A massive infusion of innovation will be utterly necessary for Sears to survive, while Wal-Mart will probably continue to move up and to the right on the business model map, even as the Dead Zone chases it up and outward. Hence, the Wal-Mart of 2020 will be the same as the Wal-Mart of 1980 in name only, as the economy’s innovation process of creative destruction chases it ever forward.

Wal-Mart’s leaders, and the leaders of all retailers (including Sears,if it’s still around then), will ask themselves how they can customize the experience of shopping; Amazon does so through its delivery services, and its offer to get your purchase to you within two days,or a day, or even hours. It also offers recommendations customized to your interests, based on statistical analysis of the behavior of you plus millions of other customers. How will Wal-Mart do that for in-store shoppers?

Dynamics of technological change

It’s become an imperative to sort out how the digital world can enhance or even transform your existing, non-digital business model.

It’s quite likely that many of its initiatives will involve digital technology, for as we noted in the previous chapter, every company, even those that are not specifically technology companies, should think of themselves as technology companies, and it’s become an imperative to sort out how the digital world can enhance or even transform your existing, non-digital business model.

Netflix is a digital entertainment business, and because viewer recommendations are so important to its success, in 2009 the company sponsored a contest in which it paid a prize of $1 million to the programmers who best improved the accuracy of its user recommendations. It’s quite obvious that the goal of the prize is also to move Netflix upward on the map, toward still better customization.

The point, obviously is that you may also be able to use the business model map to help you think about the future of your business, to compare your own company’s performance to your competitors, and to conceive of the initiatives that will take you in the direction you want to go.

For another example let’s look at auto markets, where a $45,000 Lexus competes successfully with a $65,000 Mercedes. The $25,000 Chevrolet is situated quite purposefully in the center of the market, similar in brand identity and corporate culture to Sears. For decades the center was a profitable spot, but no more, and like Sears, Chevrolet was left behind due to growing customer expectations. The failure of Chevrolet to innovate was indeed a big part of the problems that GM CEO Rick Wagoner did not fix, and a significant contributor to the drastic decline of GM between 1995 and 2008.

So as you think about your own business you will seek to identify where customization can be offered to enhance the attractiveness of your products and services, and where perhaps the market can be enlarged by lowering prices, thereby moving your entire business model continually upward and to the right. This may not be optional, and indeed, when we look at the companies that have failed, we often see that their competitors offered either lower prices, or more customized solutions, or both.

For example, you may remember that in its early days, Google had a lot of search engine competitors, but over time they have all fallen away simply because the search results that Google provided were simply better, i.e., more customized to the specific requirements of searchers. This is a great example, by the way, of the winner-take-all dynamics of technology markets.

There’s no limit to the business factors that could become important in future markets, and which some firm other than Google may master.

Remember, though, that this does not mean that Google will forever be entrenched as the exemplary search company, because there’s no reason to expect Google to retain its dominance forever. There’s no limit to the business factors that could become important in future markets, and which some firm other than Google may master.

Indeed, as noted above it’s very often when the key drivers of competition change that old companies are pushed aside, and new ones take their places as leaders. And this happens precisely because it is so often the new firms that master new competitive factors first.

We saw this with Nokia, and now we may be looking at the same process with Microsoft. The tech colossus is still dominant in many fields, but is struggling to adapt to markets that are rapidly changing. Sales of the PC are declining worldwide, down 10% from 2012 to 2013, while sales of tablets are increasing, but Microsoft is not benefiting much from this because it did not foresee the tablet market, and came quite late with its Surface.

This is quite consistent with the company’s history as a follower rather than a leader. How many of Microsoft’s products are copies of innovations from others? It’s a long list, beginning with DOS, Windows, and Office, which were copies of CP-M, the Mac OS, and Word Perfect / Lotus 123, and then Explorer which copied Netscape Navigator, Bing which is a copy of Google, etc. This shows that a company can be hugely successful as a clever copiest, and even as Microsoft Office and Windows remain dominant software products for PCs, the continuing decline of PC sales requires the company to fight a rear guard action to preserve the past, rather than a proactive one to create the future. We can well foresee that when PC sales drop below some currently-undefined threshold, then Microsoft itself may follow in the footsteps of Nokia and Kodak, falling below the threshold of on-sustainability at which point the company implodes, most likely to be sold off in pieces for its assets.

But the leaders of Microsoft are obviously very smart, and they see what’s happening as well, or better, than us outsiders. So will they lead their company to create the next generations of products and services and business models to sustain the company in the years ahead? Will they be able to create better business model and new products and services that move up and to the right on the matrix,faster and better than their competitors? The hypothesis here, and the logic of business model warfare, suggests that this should be one of their overriding objectives, and perhaps a convenient (although certainly quite simplified) way to assess any given decision or proposed initiative.

The upper right corner, meanwhile, remains an interesting sort of business Xanadu. Here you might find an entirely customized product, which is affordable by literally everyone, because instead of having to pay for it, it’s free. Air, for example, is such a product—essential, free, and (in most places) abundant.

But surely the upper right could not be the location of any company, for how would it survive?

G-spot in the value matrix

In fact, however, there are currently two companies occupying the super desirable corner, and their astounding success has been achieved precisely because their products (well, services really) are utterly free and yet totally customized to the uniqueness of each “buyer’s” specific requirements.

One of these companies is Google, which is happy to provide you with a fully customized web search at any time, day or night. It takes only milliseconds, and the company performed this hugely valuable service approximately 2 trillion times in 2013, creating 2 trillion generally satisfied customer experiences. Breaking down this huge number, we see that searches were performed on average 6 billion times per day, or 4 million per minute, or thus about 70,000 per second. (I found out the total number by doing a Google search, of course.)

An additional interesting result comes when we divide 2 trillion searches by the approximately 7 billions humans, which tells us that on average, each of us searched Google about 300 times in 2013, or about once a day. (On some days I myself search Google 20 or 30 times, and most newborn babies don’t use Google at all, so the average just gives a general idea of how well used this service is.)

It is in honor of Google that the name of the super sweet spot in the upper right corner of the value matrix is the “g-spot.”

Overall, it’s quite remarkable what the company has achieved, and how important its services have become, and still even more remarkable that all these services are free. Hence, it is in honor of Google that the name of the super sweet spot in the upper right corner of the value matrix is the “g-spot.”

Google’s magnificent business model has created a goodly number of billionaires from among the founding team precisely because the company is so well and uniquely positioned, because they do indeed seem to fully understand the extraordinary position it occupies, and because the firm is so amazingly well managed to exploit and extend its significant advantage. Microsoft’s Bing, meanwhile, plays follower, a position we are accustomed to seeing a Microsoft product occupy.

There is another company also now occupying the g-spot, sitting beside Google with a complementary competing business model. This is Facebook (should we call it the “f-spot”?), which is also an entirely free service, one also utilized by millions.

Interestingly, while Google’s success is based on its 100% customization of search results, Facebook’s is also built entirely on total customization, but in Facebook’s case the customization is provided by you, the user, because you’re the one who creates your Facebook page, and nearly a billion of us are happy to participate.

Facebook has also created billionaire owners, and they also seem to understand their unique situation.

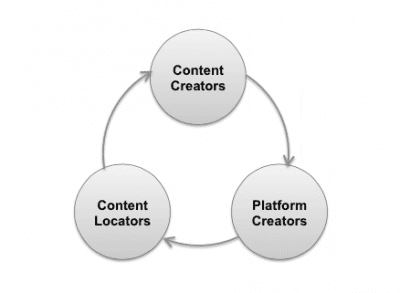

And actually Google also relies on us to do the customization, as we’re the one who are creating the 180 million + web sites that Google searches for us. This is a profound partnership between content creators, us, platform creators such as Facebook, and content locators such as Google and Bing.

This triad constitutes a hugely significant phenomenon for all future businesses and business model innovators. Study it deeply to understand, exploit, and further develop what the internet age now has made possible, because it is here that we can anticipate many innovations and surprises in the future, particularly as computers become faster, more powerful, less expensive, and still more ubiquitous.

This triad constitutes a hugely significant phenomenon for all future businesses and business model innovators. Study it deeply to understand, exploit, and further develop what the internet age now has made possible, because it is here that we can anticipate many innovations and surprises in the future, particularly as computers become faster, more powerful, less expensive, and still more ubiquitous.

Along these lines, there’s another example that suggests the validity of the model, the PC itself. As s device, the PC has gotten considerably less expensive, exceptionally more powerful, and profoundly more customizable over the last 30 years. The entire PC industry has moved significantly up and to the right, especially if you consider your smart phone to be a PC, which would be accurate. But it’s even more accurate to think of a smart phone as a supercomputer, as today’s iPhone has roughly the same computing power as a supercomputer of three decades ago. If the folks at Nokia had been thinking about their product in these terms, rather than as “cell phone,” then perhaps they would have been better prepared for the destruction that the iPhone did to their business model.

You get the point, which is that for the majority of firms that compete in the physical world of products and services for which they must charge money to survive, which is nearly every company, the g-spot is an incredibly enticing destination, but one that they will never actually attain. Still, this is direction toward which you are always compelled to strive through your innovation efforts.

The basic issues and concerns are more or less the same which can be expressed as … How to achieve more customization, and how to reach more customers.

Further, just about every type of competitive advantage can be represented on the map, so whether you’re selling products or services doesn’t seem to matter, as these two basic variables encompass nearly all business concerns, nor does it matter it you’re selling to consumers or to other businesses, or if you’re in government or the non-profit sector; the basic issues and concerns are more or less the same which can be expressed as … How to achieve more customization, and how to reach more customers.

Where are you on the map?

As a practical exercise, please locate your business and the businesses of your competitors on the map. What’s different between your business and theirs? Do they target higher prices and a more selective clientele? Then they would be perhaps up and to the left of yours. Do they offer steep discounts and seek a larger market share? Then they would be down and to the right.

The important issue to consider is the direction in which things are headed. In your ideal situation, which spot on the map would you prefer to occupy? Can you define a pathway from where you are now to where you’d like to be? That could well be your innovation pathway, and in the quest to target the right innovations to be working on, you can use this possibility as one key aspect to address: Does this innovation help our organization move to a better spot on the map?

Similarly, you should also consider what spot your competitors would like to occupy, and think about how they might they get there.

If you mark these targets also, and draw an arrow from the current location to the future preferred location, what do you learn? Is everyone in the market trying to get to the same location? If so, how do customers distinguish between the players? Do any companies in the market have a distinctive brand identity that confers a branding or positioning advantage?

Or are all the competitors just trying to lower their prices to attract more market share, leading to a price war? Or perhaps they’re trying to gain market share by adding services without raising prices.

We recognize that these questions, and the way we’re asking them, are oversimplified, but despite this drawback the questions themselves are nevertheless quite important to ask, and hopefully they will provoke some useful thinking for you and productive dialog among your team. The right questions, even simplified ones, can lead to answers that may be quite important because they may help us to identify the patterns that lead us to make the right choices, choices that result in strategic advantage. And since we’re inevitably dealing with situations of incomplete information, then we look for the patterns that can lead us to useful answers.

As we have already mentioned at the beginning of the book, questions are critically important strategic allies for us in this journey.

Article series

The Innovation Formula: the guidebook to innovation for small business leaders and entrepreneurs

1. Innovation in the SME and Entrepreneurial Context

1. Innovation in the SME and Entrepreneurial Context

2. Elements of The Innovation Formula

3. Five Forces of Complexity and Change

4. → Market Mapping for Sustainable Growth

5. Risk, Great Ideas, and Your Business Model

6. Risk and Your Innovation Portfolio

7. Designing Your Innovation Portfolio

8. Build a Fast and Efficient Innovation Team

9. Speed of Innovation – How to Master Rapid Prototyping

10. Full Team Engagement in the Innovation Culture

11. To be a Good Leader, Be a Good Learner

12. Key Abilities of Effective Innovation Leaders

13. Four Tools to Support Creativity and Innovation

14. Taking Action: Your Innovation Master Plan

15. 25 Steps to Jump-Start your Innovation Journey

About the author:

Since 2001, Langdon Morris has led the innovation consulting practice of InnovationLabs LLC, where he is a senior partner and co-founder. He is also a partner of FutureLab Consulting. He is recognized as one the world’s leading thinkers and consultants on innovation, and his original and ground-breaking work has been adopted by corporations and universities on every continent to help them improve their innovation processes and the results they achieve. His recent works Agile Innovation, The Innovation Master Plan and Permanent Innovation are recognized as three of the leading innovation books of the last 5 years.

Since 2001, Langdon Morris has led the innovation consulting practice of InnovationLabs LLC, where he is a senior partner and co-founder. He is also a partner of FutureLab Consulting. He is recognized as one the world’s leading thinkers and consultants on innovation, and his original and ground-breaking work has been adopted by corporations and universities on every continent to help them improve their innovation processes and the results they achieve. His recent works Agile Innovation, The Innovation Master Plan and Permanent Innovation are recognized as three of the leading innovation books of the last 5 years.

Photo: 3d coordinate system from Shutterstock.com