Planning for the unplanned, developing systems where complex and highly scaled behaviour can unleash random breakthroughs at the same time as providing systemic innovation, is extremely important. But the ad hoc starts with a structure and a plan. That’s what we need to understand more of.

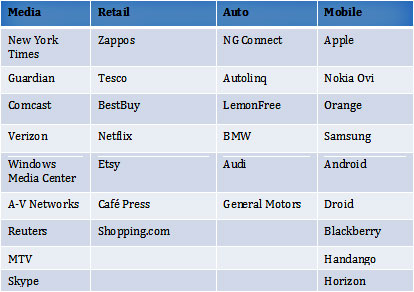

Here is a shortlist of companies running ad hoc programs that I sketched out 3 months ago. It is only a partial list:

These are in the main giants in their field. The ad hoc or ecosystem innovation platform is very real.

Ad hoc innovation usually revolves around some form of technology platform – perhaps an ideagora but more likely an apps program, for example the Apps Store for Apple’s iPhone or a more intimate application programming interface (API) project like that run by Britain’s largest retailer Tesco which currently has one app as compared to Apple’s 200,000.

Ad hoc innovation can be as awesome as Apple or as conservative as Tesco. It differs from clustering in the important sense that it lacks formal relationship structures, it tends not to over-define its purpose, and it appears to leave more to chance.

The purpose of this article is to suggest that once we understand the underlying formal processes in ad hoc innovation we will be better able to incorporate it into policy making. That in turn has four interesting consequences:

- Ad hoc innovation – or the chance element – becomes more predictable and open to planning and investment considerations

- Ad hoc innovation can be integrated into cluster and value network innovation and be a part of any regional, city or enterprise innovation process

- We can develop skill sets around ad hoc innovation

- We can make all innovation systems less geographically dependent, which will give regions and cities more scope to draw talent into an innovation strategy without physical movement and carbon expenditure

Now, I realize that an explanation of method can be unexciting so if method is not your interest skip on to the last section where I will discuss why this is so important to policy.

Ad hoc processes

I’m going to limit the amount I say about ad hoc innovation in order to keep the story simple. I’m happy to engage in a dialogue about it but I think that right here, right now, we need to understand more about the formal processes so we can see experiences like Apple’s as replicable and, potentially, policy driven.

An ad hoc innovation process has three main phases:

1. Defining the relationship with the outside world

2. Devising a way to aggregate contributions from the outside world

3. Devising a way to sell, evangelize or otherwise engage an audience for the products or services in the ad hoc ecosystem.

1. Defining the relationship with the outside world

An ad hoc innovation program needs a way to interact with an indeterminate section of the developer or content population. The way to do that is, usually, to design an API (application programming interface) that defines what you will give that population access to, to help build your partnership with them.

The design of the API and the data or content these putative partners can access is of course crucial. It needs at least these components:

- A software development kit and code samples.

- A web site where parties can share experiences, data, tricks and code, and where news and progress can be announced usually through a blog which can also be an advocacy platform.

- A publishing program that sets out what you will be doing to get people’s initiatives to a wide enough audience

- A strategy to attract the best talent into your program.

2. Devising a way to aggregate contributions from the outside world

You could interpret this as ‘set up an app store’ and plenty of companies are doing that. There’s no reason why the public sector can’t also do this and indeed open data projects are springing up. But an app store is not the only way of expressing how the contributions from a collaborative community can find their way into one place with one identity. Many organizations are choosing more intimate environments. For example the Guardian has a ‘gallery’ that exhibits its open content initiative. And you can imagine other metaphors that are not so commerce driven as the apps store.

In terms of process what we are looking at here is an ingest-system, a way to get apps and content into an aggregation platform.

That means a platform and process to perform:

- A copyright compliance check

- A compatibility check

- A process for meta-description of the content or app

- A catalogue process

- Quality assurance

- Publishing

3. Devising a way to sell, evangelize or otherwise engage an audience for the products or services in the ad hoc ecosystem.

The final step is to sell the outputs. In the case of the iPhone, coupled to a beautiful and desirable device, that has also meant global advertising and evangelism. So success stories have sophisticated outreach systems attached. But the store or gallery or (choose your analogy) needs formal processes in which people feel safe to transact and where faulty product can be rectified or where new versions of product can be accessed. An apps store is a sophisticated environment incorporating:

- The content database

- The end user client (e.g. what sits on the mobile or web)

- The transaction system

- Incentive systems that bring people back (e.g. games that have different levels that need further downloads)

- Internationalization of all this

- Marketing

- Evangelism and affiliate programs

- Public events

The relevance to policy

So that’s some of the detail. I set it out just to demonstrate that ad hoc means a lot of planning and a good deal of knowledge and experience. In order to create the opportunity for random factors like chance, you need to have substantial amounts of structure.

As more and more companies take this route it brings into question how clustering strategies might open up and take advantage of the vast world of skilled and talent people who are ready to commit entrepreneurially to innovation.

1. Closed vs open

By their nature clusters tend to be closed. But we are living in a borderless world. To remain relevant they need to extend their geography. Especially as we move towards more open forms of Governance we need to look at openness and cluster policy.

2. The role of chance

It’s worth also remembering that when Michael Porter first wrote about clusters he was unable to leave aside the fact that chance also plays a role. To open up to chance clusters need to create conditions where positive random effects are likely to occur.

3. Clusters, democracy and talent

Clusters tend towards an elitist view of themselves and the innovation process – they are after all “clusters of excellence”. But innovation happens in many ways. We are gravitating towards a view that recognizes out highly educated societies as being replete with talent. Talent is not short – finding ways to access it are the main constraint. Innovation is multidimensional enough that cluster policy needs to target also the many millions of people who are out there waiting on a chance to contribute.

4. Clusters, ad hoc innovation and the changing nature of ecosystems

Finally the nature of ecosystems is changing. When they first appeared in management literature they involved a kind of first outing for co-opetition. They were a way to form partnerships globally so that enterprises could extend their reach. Today in a networked world they are much more about social interaction around product related issues and their significance is that they contain significant potential but often unrealized value. Being smart enough to realize value, to convert relationships into revenue is tomorrow’s enterprise advantage. These interactions take place as much in ad hoc systems as they do in clusters. Policy makers really cannot afford to ignore such a significant source of value creation.

By Haydn Shaughnessy, contributing editor

About the author

Haydn Shaughnessy, senior editor, has worked at the epicentre of innovation in a 25 year career spanning journalism, consultancy and research management. He began his technology career as a manager of application research in broadband, mobile and downstream satellite services and has maintained a continuous production of analysis and intellectual material around innovation since then, having written on Wired Cities, Fibre to the Home, Future Search Engines, and international collaboration. He is an emerging thought leader in systemic innovation building on his PhD research in large scale economic transformations. He was previously a parter at The Conversation Group, the leading global social technologies consultancy where he helped companies such as Alcatel Lucent, Volvo, General Motors, Symbian Foundation, and Unilever adapt to the current transformations in the global digital economy. He has written for the Wall St Journal, Forbes.com, Harvard Business Review, and many newspapers as well as making documentaries for the BBC, Channel 4 and RTE. His consultancy and research work encompasses changing enterprise structures, new business models and long-term trends in attitudes. He is in demand as a speaker on the impact of changing attitudes on business and on gearing innovation to new consumer requirements.

Haydn Shaughnessy, senior editor, has worked at the epicentre of innovation in a 25 year career spanning journalism, consultancy and research management. He began his technology career as a manager of application research in broadband, mobile and downstream satellite services and has maintained a continuous production of analysis and intellectual material around innovation since then, having written on Wired Cities, Fibre to the Home, Future Search Engines, and international collaboration. He is an emerging thought leader in systemic innovation building on his PhD research in large scale economic transformations. He was previously a parter at The Conversation Group, the leading global social technologies consultancy where he helped companies such as Alcatel Lucent, Volvo, General Motors, Symbian Foundation, and Unilever adapt to the current transformations in the global digital economy. He has written for the Wall St Journal, Forbes.com, Harvard Business Review, and many newspapers as well as making documentaries for the BBC, Channel 4 and RTE. His consultancy and research work encompasses changing enterprise structures, new business models and long-term trends in attitudes. He is in demand as a speaker on the impact of changing attitudes on business and on gearing innovation to new consumer requirements.