By: Jean-Philippe Deschamps

Innovation governance can be thought of as a system of mechanisms to align goals, allocate resources and assign decision-making authority for innovation, across the company and with external parties. In this series of articles, professor Jean-Philippe Deschamps delves deeper into this topic; what is innovation governance, what different models are there and which ones seem to be the most effective?

How can companies effectively steer and manage a complex, cross-functional and multidisciplinary activity like innovation? Most companies are organized to manage business units, regional operations and functions. Many have gone further by allocating specific responsibilities and setting up dedicated mechanisms to manage cross-functional processes, for example new product development. But how can they stimulate, steer and sustain innovation, an ongoing transformational endeavor that is increasingly becoming a corporate imperative?

Certainly, innovation consists of several cross-functional processes from generating ideas to taking technologies to market, but there is more to it. It deals with “hard” business issues like growth strategy, technological investments, project portfolios and the creation of new businesses. But it also relates to “softer” challenges, like promoting creativity and discipline, stimulating entrepreneurship, accepting risk, encouraging teamwork, fostering learning and change, and facilitating networking and communications; in short, it requires a special type of organizational culture. Like marketing, innovation is a mindset that should pervade the whole organization.

To review whether your company has adopted a comprehensive innovation governance system, you need to start with three distinct types of questions regarding the content of innovation.

Current innovation management techniques and organizational solutions tend to focus on many – not all – of the hard aspects of innovation, but much less on its softer elements. The scope of innovation is so broad that few companies appear to have thought deeply about what it takes now and will take in the future to steer and manage innovation in an integrated way, across all its aspects, hard and soft.

The appointment of a dedicated, high-level “innovation czar” – whatever the title – is one possible approach to meeting the challenge and overseeing innovation in all its dimensions. But these dedicated innovation leaders are not commonly found, and besides, there are many other ways to address the innovation governance challenge than to entrust it to a single executive. The word “governance” is appropriate here because innovation is an undertaking that cannot be delegated to any single function or to lower levels of an organization. It remains a top management responsibility and preserve.

Given the newness of the term and of the concept behind it, it is important to define what innovation governance really means, i.e. to define its scope, and this is what this article will try to do. The next article in this series will identify and characterize the various governance models that companies have put in place – I have identified nine in my research. The last article will be devoted to discussing how effective these models seem to be, based on ongoing research with a number of large and medium-sized organizations.

What Must You Do When Creating a Virtual Innovation Lab?

What Must You Do When Creating a Virtual Innovation Lab?

Adopt a platform, provide experienced mentors, connect teams prior to events (and afterwards), and more. Find out other tips about creating your own virtual innovation lab by downloading this infographic.

Download Here

What does innovation governance entail?

In a recent management development seminar that I directed at IMD on the theme of innovation governance, the participants – all senior managers vastly experienced in the field of innovation – proposed an excellent list of innovation governance responsibilities:

- Defining roles and ways of working around the innovation process

- Defining decision power lines and commitments on innovation

- Defining key responsibilities of the main players

- Establishing the set of values underpinning all innovation efforts

- Making decisions that define expectations

- Defining how to measure innovation

- Making decisions on innovation budgets

- Orchestrating, balancing and prioritizing innovation activities across divisions

- Establishing management routines regarding communications and decisions.

This list provides a good first description of the scope of innovation governance. But to see how it applies in your company, it is worth going a bit further and asking: What questions does innovation governance address? Broadly speaking, it deals with both the “content” and the “process” sides of all innovation activities taking place in a company.

Questions dealing with the “content” of your innovation efforts

To review whether your company has adopted a comprehensive innovation governance system, you need to start with three distinct types of questions regarding the content of innovation, i.e. Why innovate? Where do you look for innovation? And how much innovation do you want? Good innovation governance starts with providing clear answers to these three questions.

Why innovate?

This basic question may seem mundane or unnecessary, particularly to senior managers with a strong innovation commitment, but is it in fact that obvious? Does everyone in the organization have the same clear understanding of the mission, purpose and objectives of innovation for the company? In short, does everyone know – and share – the reasons why you need to innovate and how this imperative relates to your corporate vision and objectives?

Answers to the “why” question will vary from company to company, and for the same company from time to time depending on economic, competitive and environmental circumstances. For example, companies in a strategic stalemate position, with few opportunities to compete effectively, may look at innovation as a way to generate a totally new business, and hence to grow profitably. Others may expect innovation to reinforce their current businesses to win a sustainable advantage. Still others will see innovation as a powerful means to build a winning brand reputation and attract and motivate top talent. There are, indeed, many reasons to innovate.

In summary, it is not a vain exercise for the top management team to spend some time, for example in a management retreat, addressing the “why” question. It is important to iron out differences in perception and communicate the response clearly to the rest of the organization. This will be the starting point of your innovation governance mission.

Where do you look for innovation?

Defining the real purpose and objective of innovation leads naturally to the next question: Where should you focus and what should be your priorities? Of course, some will argue that innovation is needed in all business areas; as a consequence, they will promote a wide open scope for their innovation activities. But in reality, innovation will better serve the business if it focuses on what really matters for the success of the company.

What does your strategy call for? Do you need more and better new products? Are you mainly looking for lower costs? Are you searching for better service and attractive customer solutions? Do you need to develop more robust business models? Are you ready to build new ventures that will expand the scope of your business? Management cannot escape the responsibility of determining priorities for innovation, and these may change with economic and competitive circumstances.

In a real business crunch requiring drastic restructuring, you may want to call for a change in the focus of your innovation activities, for example from new product proliferation to product line rationalization and cost cutting. In the 2008 economic and business crisis, a number of socially responsible companies benefited from launching a specific innovation drive to unleash operational savings opportunities. In this way they achieved part of their cost-cutting objectives while minimizing job cuts, thus maintaining employee morale and preparing for an economic upturn.

Clearly defining and broadcasting the focus and priorities of innovation – where and on what you shall innovate – is therefore a second vital element of innovation governance.

How much innovation do you want?

There are two very different types of “how much” questions. The first deals with the intensity or ambitiousness of your innovation efforts and your innovation risk portfolio, while the second refers to the issue of innovation funding.

Defining how much innovation you want is important in determining the risk you are ready to bear to meet your objective – be it building a revolutionary new market category or developing an advantage over competitors – and the sustainability of the anticipated reward. In other words, are you searching for breakthroughs, and hence accepting a high level of uncertainty? Or do you instead favor a more prudent approach by encouraging a series of incremental innovation moves? Or do you expect both and, if so, in what proportions and for what objective? These questions need to be clarified to ensure that your staff members fully understand the company’s risk/reward boundaries in their search for new ideas.

Defining how much innovation you want is important in determining the risk you are ready to bear to meet your objective.

But determining how much innovation you want is also important from a funding point of view. Breakthrough innovations should not be pursued unless you are ready to commit the necessary resources to implement them fully and market them aggressively. It is not uncommon to see companies having to shelve promising radically new product or service concepts simply through lack of resources, given the current demands of their existing business. Such unproductive developments might have been avoided if management had expressed clearly from the start its innovation expectations and investment constraints, a definite part of its innovation governance mission.

Questions dealing with the “process” by which you innovate

Good innovation governance requires three additional questions to be addressed regarding the practical aspects of your innovation activities, i.e. How can you innovate more effectively? With whom should you innovate? And who is going to be responsible for what regarding innovation?

How can you innovate more effectively?

Judging by the number of books, research articles and public seminars devoted to the practical aspects of innovation, this question is, and will remain, on the agenda of most companies, even the most innovative ones. It has also triggered the growth of many service providers and consultancies to guide you in your quest. How can you boost innovation? What approaches should you adopt to meet your innovation objectives? How can you mobilize your organization behind this challenge? Employees expect clear direction from management to help find the answers.

These questions, which are at the heart of any innovation governance initiative, deal with process issues, i.e. What process will take you most time- and cost-effectively from new market needs and ideas to successful market introduction? What organization does this require? What tools should you use for implementation? What measures should you track? But they also raise a number of culture challenges which management somehow has to address despite their complexity. How do you foster a climate that combines creativity and discipline? A culture in which sensible risk is encouraged? An environment that facilitates networking and communication in all directions? A compensation system that encourages entrepreneurship and teamwork?

With whom should you innovate?

The concept of “open-source innovation” – building on ideas and technologies from third parties – has been promoted by a few scholars[1] and exemplified by prominent innovative companies like P&G[2]. It is now pervading most businesses. Many companies advocate it as part of their innovation strategy, but advocating it is not enough. It is the responsibility of your management team to define its purpose – why do you engage in open innovation? Its scope – what are you looking for and how far are you ready to go in your partnership and alliance strategy? And its implementation process – how should you proceed to create win-win opportunities? Companies that have embraced the open innovation challenge, like P&G and Philips among many others, have clearly included it in their innovation governance agenda.

Who is going to be responsible for what regarding innovation?

The “who” question is the last, but by no means the least important, of all innovation governance questions. It deals with the definition and allocation of specific innovation management responsibilities at all levels. As part of it, management needs to choose the overall governance model or mechanism that will stimulate and orchestrate all innovation activities in the company. It will identify the owners of all key innovation processes and help in deciding whether or not to allocate innovation management responsibilities to a dedicated group of managers, as opposed to current business and functional managers. If dedicated innovation managers, whatever their title, are appointed, management will have to define their role, reporting level, resources and degree of empowerment vis-à-vis the line organization and other established staff functions.

In summary, if sustaining innovation is an important corporate objective for your company, make sure that you explicitly address the six questions listed above – three on “content” and three on “process.”

How broadly should innovation be defined?

One of the key roles of management in governing innovation is to ensure that the term itself is defined very broadly, something that is sometimes overlooked. At IMD, when we contacted our clients’ management development specialists to market a new program – Managing the Innovation Process – these HR officers often directed us to their R&D colleagues, as if innovation was the exclusive preserve of technical functions. This reflected a general belief that innovation deals with new products and new technology. We had to fight that prejudice to attract managers from other functions to our seminars and convince them that there is much more to innovation than R&D. This is why it is so important to stress that one of the key tasks in innovation governance is to promote and steer all aspects of innovation, not just new products.

One of the key tasks in innovation governance is to promote and steer all aspects of innovation, not just new products.

Defining innovation broadly means at least three things for senior managers. It involves enriching projects through multiple innovations, paying attention to all the specific processes within innovation, and combining top-down and bottom-up innovation, as outlined below.

Enriching projects through multiple innovations

Management must ensure that the company innovates in all aspects, not just products or technology, and – even more importantly – it needs to encourage the organization to search for combined innovations. Products or services that have enjoyed a strong market position over the past decades – think of Apple’s iPod/iTunes, P&G’s Pringles potato chips and Ikea’s furniture business – are the result of combined innovations. They all embodied innovations in product concepts, of course, but they also brought together new approaches in business organization, business models, processes, services, and marketing (channels, branding and customer experience).

The power of combined innovations is so potent in creating a sustainable competitive advantage that some companies expressly demand it. Managers at Danish toy manufacturer Lego, for example, require project leaders to show how they plan to reinforce the success rate of their future new products by rethinking many other aspects of their internal value chain, i.e. by proposing multiple additional innovative features in their projects. This means that project review committees have to include managers with a broad perspective on innovation.

Paying attention to all the specific processes within innovation

Management must also make clear that innovation extends well beyond the traditional project-related processes that companies often call NPD (New Product Development). Innovation starts before and ends after NPD! In my previous book, Innovation Leaders,[3] I proposed a broad look at innovation by paying attention to its eight constituent “I-Processes.” Four of these relate to the creative invention phase:

- Immersion (in the market and the technology)

- Imagination (of an opportunity)

- Ideation; and

- Initiation (of a formal project).

and the other four deal with the disciplined implementation phase:

- Incubation (of the project)

- Industrialization

- Introduction (in the market and rollout); and

- Integration (of your offering into the customer’s operations).

Many companies see the NPD process as starting with ideation and ending with industrialization, which is a rather narrow perspective. As part of their governance duties, senior managers need to insist on the first two of these processes, which create the context within which innovation will take place, and the last two, which will shape market success.

Combining “top-down” and “bottom-up” innovation

Thinking about innovation broadly raises the question of its origin or mode of occurrence. Innovation can indeed be a spontaneous bottom-up phenomenon, driven by the creativity and entrepreneurial spirit of your staff. But it can also result from a visionary and ambition-led, top-down initiative introduced by management. The two modes of occurrence are of course not mutually exclusive.

Some companies have a strong tradition of bottom-up innovation. They rely on initiatives from staff and give them the necessary freedom to come up with new ideas and concepts, which may lead to new business opportunities. In these companies, management sees its role as promoting and supporting front-end innovators, shielding them from possible “idea killers.” It also focuses its intervention on filtering ideas and funding the best ones. Archetypal innovators like 3M and Google probably exemplify bottom-up innovation at its best. Their management has set up systems and rules to support it, notably giving individuals the freedom to work on their own ideas (15% of their time at 3M and 20% at Google). Creating these innovation-enhancing systems and rules is an important part of innovation governance duties.

But relying on bottom-up innovation alone may be insufficient, particularly when circumstances or opportunities require the launch of major costly or complex innovation initiatives in a top-down mode. This type of management-inspired innovation is often found in Asian companies, particularly in technology-intensive industries requiring major R&D and capital investments. It requires the ability to build and share a vision; a talent for mobilizing the organization behind that vision; and determination to persevere in spite of possible initial problems.

So, understanding the conditions under which bottom-up and top-down innovation will prosper; determining the right balance between them; and adopting management attitudes that will facilitate the two innovation modes are essential elements of innovation governance.

The innovation governance triangle

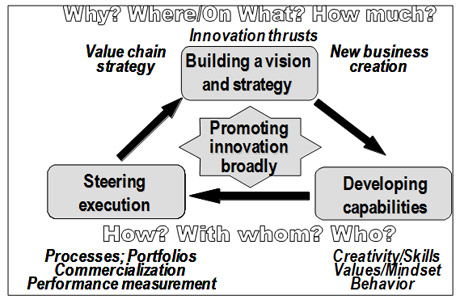

This long list of questions can be summarized in a simplified triangle form in Figure 1.

Innovation governance starts with building a vision and strategy for innovation. This high-level strategy will determine the position of the company in its value chain, the competitive thrusts that innovation should enable, and its objectives and approach to the creation of new business. These should concretely answer the “why?”, “where/on what?” and “how much?” questions listed above. But it does not stop there! Innovation governance is also concerned with the development of innovation-enhancing capabilities, not just hard skills but softer ones as well. In addition, it deals with the organization of the classic tasks linked with execution. These, in turn, should explicitly answer the “how?”, “with whom?” and “who?” questions.

The second article in this series on innovation governance will list the nine models that I have identified in my research, ranked in their apparent order of popularity. The last article in this series will highlight the models that companies seem to find the most effective.

Footnotes

[1] Open Innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology by Henry W. Chesbrough, Professor and Executive Director at the Center for Open Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, 2003.

[2] “Connect & Develop: Inside P&G’s New Model for Innovation,” by Larry Huston and Nabil Sakkab, Boston, Harvard Business Review, March 2006.

[3] Innovation Leaders: How Senior Executives Stimulate, Steer and Sustain Innovation, by Jean-Philippe Deschamps, Chichester, Wiley/Jossey-Bass, 2008.

About the author

Jean-Philippe Deschamps is emeritus Professor of Technology and Innovation Management at IMD in Lausanne (Switzerland). He has more than forty years of international experience in consulting and teaching on innovation. He was the co-author of Product Juggernauts: How Companies Mobilize to Generate a Stream of Market Winners (1995; Harvard Business School Press) and the author of Innovation Leaders: How Senior Executives Stimulate, Steer and Sustain Innovation (2008; Wiley/Jossey-Bass).

Jean-Philippe Deschamps is emeritus Professor of Technology and Innovation Management at IMD in Lausanne (Switzerland). He has more than forty years of international experience in consulting and teaching on innovation. He was the co-author of Product Juggernauts: How Companies Mobilize to Generate a Stream of Market Winners (1995; Harvard Business School Press) and the author of Innovation Leaders: How Senior Executives Stimulate, Steer and Sustain Innovation (2008; Wiley/Jossey-Bass).

Innovation Governance in Theory & Practice Collection:

- → What is Innovation Governance? – Definition and Scope

- 9 Different Models in use for Innovation Governance

- Innovation Governance – How Well Does it Work?

- Governing Innovation in Practice – The Role of the Board of Directors

- Governing Innovation in Practice – The Role of Top Management

- Imperatives for an Effective Innovation Governance System

- Innovation Governance: Why Should Top Management Care?

- 10 Best Board Practices on Innovation Governance – How Proactive is your Board?

Photo by Mimi Thian on Unsplash