By: Jean-Philippe Deschamps

In this article, the final in a series of six, Professor Jean-Philippe Deschamps, discusses the imperatives for an effective innovation governance system. Innovation performance is often not directly dependent on the type of governance model used. Rather, innovation performance reflects the strength of top management’s commitment and engagement, and the credibility, skills and energy of the actors who under take the governance mission.

Does this imply that all the governance models listed in the second article of this collection are equivalent in terms of effectiveness? The answer is obviously no, and the third article in the same series highlighted significant differences in levels of satisfaction with them. The question that remains open is whether these differences in satisfaction reflect the nature of the model – would some be more effective than others? – Or rather the way the model has been implemented. We generally favor the second alternative: Each model can be made to work well; it just depends on the attention and care with which it is put in place and managed.

To help top management teams reflect on the effectiveness of their governance models – a prerequisite for improving them –we propose a number of evaluation criteria, or imperatives. These criteria represent generic success factors for any type of governance model. The conditions are not model-dependent – they reflect instead how a model has been specifically implemented in a company. We have identified and will discuss eight of these success factors:

- The level of commitment and engagement of the top management team – particularly the CEO – behind the chosen model.

- The breadth and depth in the scope or coverage of the implemented model, in terms of process and content, as well as hard and soft issues.

- The relative independence of the model with regard to the unique personality and skills of a single individual, i.e. its robustness vis-à-visa change of actors.

- The ability of the model and its key actors to gather broad and proactive support from the rest of the organization.

- The inclusion of adequate checks and balances in the model, as well as processes and tools for continuous performance evaluation and improvement.

- The robustness of the model vis-à-vis external pressures and crises, in terms of allowing the company to ‘stay the course’ and meet its long-term innovation performance objectives.

- The capacity of the model to evolve, enlarge its scope and grow with the company, particularly when operations and market coverage are being globalized.

- The clarity and accessibility of the governance model for the board of directors, for information and auditing purposes.

Commitment and Engagement of the CEO and Top Management Team

Truly innovative companies have this feature in common – their top management team, starting with the CEO, is genuinely committed to turning innovation into a core competence of the corporation. This is in contrast with quite a few other companies we know, whose management seems only to pay lip service to innovation.

Interestingly, most of the companies covered in our research can be characterized as having gone through a succession of innovation-fervent CEOs over at least a couple of decades. In each of these companies, we speculate, so strong is the CEO’s mark on the company’s innovation psyche that it would be almost unthinkable to see a new CEO coming into the top job without sharing the same passion for innovation as his/her predecessor. Companies that have not experienced a succession of innovation-oriented CEOs in the past can still ‘join the club’ with a new CEO, but this will require a particular effort on the part of the newcomer to break with the past and create a new and lasting innovation legacy.

Truly innovative companies have this feature in common – their top management team, starting with the CEO, is genuinely committed to turning innovation into a core competence of the corporation.

The personal commitment of the CEO to governing innovation proactively – whether directly or indirectly through an appointed leader or group of leaders – is generally shared by several members of the executive team, typically those dealing with technology, products and new business development. These senior leaders usually play an essential role as ‘relayers and amplifiers’ of the CEO’s engagement. Other leaders in charge of operations, financial management and corporate administration may not participate directly in innovation activities but they should be expected to be, at least, sympathetic toward its overall direction and to support it. Special mention should be made of the chief human resources officer (CHRO), generally a key member of the executive committee.

In many companies, these leaders are left out of innovation discussions and initiatives. Yet, they are essential in ensuring that there is an adequate supply of innovation leaders within the organization through recruitment, performance evaluation and rewards, and career planning. They are also the most likely candidates to launch an assessment of the innovation culture or climate of the company before trying to improve it. In some particularly motivated companies, CHROs can also become involved in coaching people and projects – just like their business colleagues –and in organizing corporate-wide innovation events and award celebrations.

Even if they are not the prime drivers of innovation, CEOs and senior leaders express their commitment and support of the company’s innovation agenda in many different and complementary ways.

First, they can set the broad context in which innovation will take place, and this means establishing bold innovation and growth objectives for the company, as well as defining innovation targets and priorities. This also includes measuring progress and tracking results.

Second, they can propose a number of values to guide the behavior of both leaders and staff and communicate extensively about these values. Innovation is often part of these values, of course, but many other values not directly linked to innovation in fact support the company’s innovation agenda, at least indirectly. P&G’s famous ‘5E’ leadership model does not mention the word innovation per se. However, its five leadership priorities – envisioning; engaging; energizing; enabling; and executing – can clearly be seen as indirect innovation leadership values. CEOs of innovative companies constantly reinforce these values in their words and deeds, i.e. in their concrete decisions and performance reviews.

Third, CEOs and members of the top management team can convey their support for innovation by allocating resources to it. One of the most visible signs of their commitment to innovation is choosing the best people to lead innovation activities. When a star performer is chosen, then a clear message is sent to the organization about the importance of innovation. Another visible sign of commitment is through innovation budgets and the funding of high-risk/high-reward projects.

Last but not least, CEOs and C-suite members can show their commitment to innovation through a number of highly visible moves, some concrete, others more symbolic. In the concrete category, senior leaders, including the CEO, can volunteer to coach important and risky projects or new businesses, for example by chairing their board. They can also make it clear that they will stay the course and maintain R&D spending levels even in difficult times. On the more symbolic front, CEOs can make a point of visiting their R&D labs regularly to talk to scientists and engineers about the nature of their work and show interest. Personal participation in innovation events like award ceremonies conveys the same message – management cares!

Breadth and Depth in the Scope or Coverage of the Model

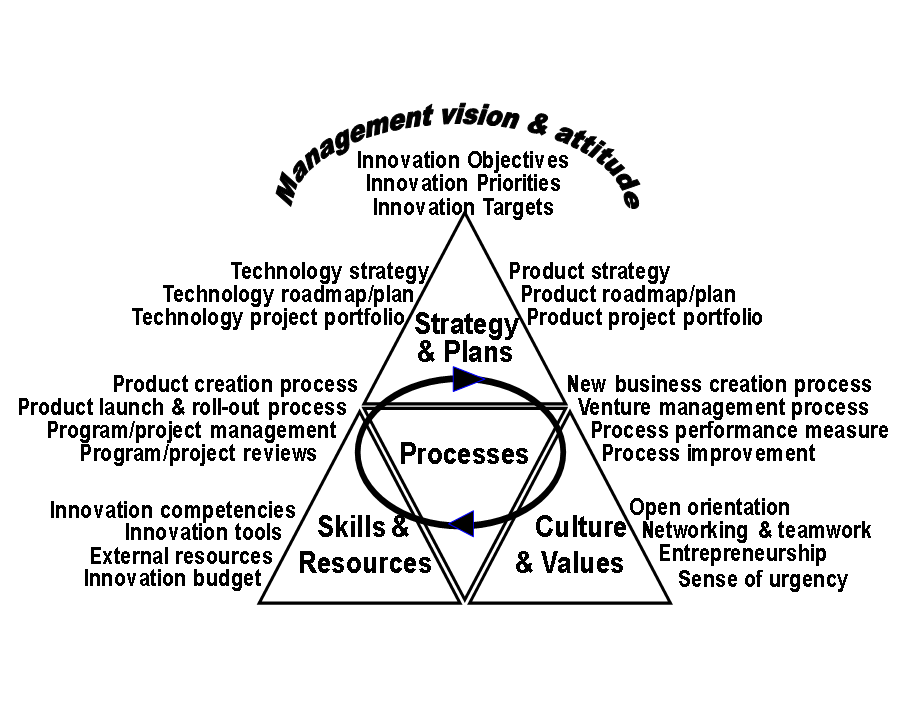

An effective innovation governance system should be geared to handle all facets of the company’s innovation agenda. It starts with a top management vision and attitude regarding innovation – reflecting the commitment and engagement mentioned earlier – and the setting of broad innovation objectives and priorities. It should also cover:

- The company’s strategies and plans regarding new products and technologies;

- Its processes, for both the creation and the launch of new products and services, as well as for venturing into new businesses;

- Its culture and values; and finally

- Its resources in terms of people, skills and budgets.

These innovation dimensions must be mutually compatible and reinforcing. The list of these innovation dimensions, which is summarized in Figure1 can be used by management for a quick check, i.e. which of these innovation dimensions do we cover in our innovation governance system, and which ones have we somehow left aside? Frequently, the innovation governance reality in many companies does not cover such a broad scope.

Figure1 Multiple Dimensions of an Innovation Governance System

In fact, most companies evolve through these various dimensions as they progressively try to unleash and master innovation as a management discipline. We have observed that newly founded companies – think of Amazon, Google and Facebook –do not have, or seem not to have a need for an explicit governance process. It is as they mature that it becomes imperative to make the model explicit. So, in the evolution of governance practices there are maturity phases, and we have observed three broad ones.

The first phase is evident when companies start addressing their innovation challenges through a focus on processes. This is generally when innovation deficiencies are the most visible because they translate into poor project selection, chaotic project management, long lead times and mediocre new product launches. The first changes management tends to make involve implementing a phased review process with a number of ‘project gates’ and a formal approval mechanism for proceeding from one gate to the other. These shifts toward more process discipline are often introduced by the head of technical operations, for example the CTO, backed by the business sponsors of the projects.

So, in the evolution of governance practices there are maturity phases, and we have observed three broad ones.

Then comes the appointment of fully empowered project leaders and the mobilization of relatively autonomous innovation teams. Once projects are being properly managed, other processes start moving up the priority list, typically at the frontend of innovation, e.g. customer understanding and preference mapping, inventory of technologies and competencies, and idea management; at the backend, commercialization comes to the fore.

The second phase occurs when management, after streamlining deficient processes, starts formally addressing the content of its innovation efforts, generally through strategy questions and portfolio management considerations. This can of course be done in parallel with the first phase. From an innovation governance point of view, this phase is quite different in terms of management attention and involvement because innovation portfolios are supposed to be aligned with business objectives and strategies. This requires the strong personal involvement of the top management team and the creation of different organizational mechanisms to manage the choices. Many companies, unless they experience major problems in respect of competencies, resources or organizational behavior, remain focused on the second maturity stage, which may be sufficient to increase their innovation yield substantially.

The third stage of maturity is reached when the top management team expands the scope of its innovation governance system to take a more holistic view of innovation and the creation of new businesses. This only happens when the top team –often with the CEO as the main innovation driver – considers innovation as a must have competitiveness factor and growth driver, not just a nice to have. In the quest for enhanced innovation performance, management will consider all factors – hard and soft – and will give innovation the highest priority when it comes to resource allocation. The third phase also includes the ability to enter into partnerships that open up new fields of innovation.

Independence of the Model with regard to the Unique Talents of One Individual

Some of the governance models introduced in the second article of this series – for example the subset of the top management team, or the high-level cross-functional steering group – are built around the principle of collective innovation management. In these models, a number of senior leaders either allocate specific missions to one another or collectively share the overall responsibility for innovation. In that sense, these models are much less dependent on any single individual than models that have entrusted the whole mission to a single champion, be it the CEO, the CTO or the CIO, or to a couple of leaders, e.g. a CTO and a senior business unit head.

To stay robust over time and withstand unavoidable organizational changes and staff moves, an innovation governance model should indeed avoid being overly dependent on the unique personality and skills of one person. The paradox comes from the fact that exceptional talents are always necessary to steer and govern innovation. When the chosen model relies on a single high-level leader, it is indeed critical to choose someone with a great character, personal charisma and a high level of energy, as well as a unique combination of skills, i.e. strong technical understanding, an acute sense of the market and a good dose of social, political and emotional intelligence. These are the kinds of people who can move mountains.

… an innovation governance model should indeed avoid being overly dependent on the unique personality and skills of one person.

At the same time, making everything dependent on a gifted leader can be dangerous. Highly talented individuals are often targeted by head hunters and can leave their job or be promoted. The risk is particularly high when these innovation leaders – particularly the more junior ones, innovation managers rather than CIOs – feel a lack of support from the top management team and become frustrated with their mission.

At the opposite end of the scale, depending on a single individual to drive all innovation activities in the company for too long may introduce another risk, that of losing the cutting edge. People who stay in their job too long may slowly become less motivated, not to say stale. Innovation requires regular breaths of fresh air and new blood. It is therefore the responsibility of the CEO and the C-suite to be aware of those two risks, which can be reduced in several ways. In the case of companies where the CEO is in ultimate charge, it is especially important for the board to be aware of these risks and to play a role of oversight and management when necessary.

The most obvious way to counter the risk of overdependence is to ask the leader in question to identify and coach one or several ‘understudies,’ typically by allocating several of the leader’s tasks to them. It is standard practice in most highly developed HR departments to earmark high-potential substitutes to replace existing leaders in case of need. This is particularly important for critical positions like CEOs, CTOs and CIOs. But management may also ensure that the leader in question has built a number of organizational mechanisms to leverage his/her strengths and handle part of his/her mission.

Ability of the Model to Gather Support from the Organization

Whichever governance model management chooses, it will be effective only if the people responsible for implementing the change – individually or collectively – obtain the cooperation and support of the rest of the organization for their innovation initiatives. Gathering support for change initiatives is not easy, as all leaders who have struggled to introduce a real change agenda in their company will testify. Several factors typically contribute to obtaining broad and proactive organizational support.

First, the attitude of business units and functions vis-à-vis new directions will be determined by the level of empowerment and credibility of those people entrusted with the innovation governance mission. The higher their hierarchical level and authority, the more likely they are to gain support from the rest of the organization. The highest level of cooperation will obviously be reached when the CEO is personally involved in the process. As a senior leader put it, who can oppose the direction adopted by the company when it is so strongly advocated by the CEO? Generally, all models that involve the direct participation of members of the top management team will benefit from broad support throughout the organization.

Generally, all models that involve the direct participation of members of the top management team will benefit from broad support throughout the organization.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, it will be very difficult for lower-level managers to mobilize businesses and functions behind an innovation change agenda, unless they are strongly endorsed by the top team. For example, there are major differences in empowerment between dedicated innovation managers – typically upper-middle managers reporting two levels below the executive committee – and chief innovation officers reporting directly to the CEO. The mediocre level of satisfaction with the innovation manager model in our survey can probably be ascribed to innovation managers’ relatively low hierarchical position, which prevents them from obtaining support for their initiatives.

The second factor that is required to trigger a broad following throughout the organization is the quality of management communications regarding innovation. The message should always come from top management and it should be clear and convincing in explaining why the company needs to focus on innovation and what this means in practice. It should also be frequently repeated so that it stands out in people’s minds.

The third imperative for mobilizing the organization is management’s assurance that the focus on innovation is there to stay, i.e. that it is not a‘ management flavor of the month’ but will be the way to go for years to come. This is not only a matter of communication, although it is critical. In real life, and particularly if they have been ‘burned’ before, people judge what they see, not just what they hear. They will seriously side with management if they see that concrete decisions are congruent with the original message.

…discrepancies between what they are told to do and the way they are evaluated.

A last condition for gathering organizational support is to ensure that managers at all levels are not caught up personally in conflicts linked with potential discrepancies between what they are told to do and the way they are evaluated. This is a classic pitfall of many change programs – performance evaluation criteria do not correspond to the company’s new priorities. Such discrepancies are often rapidly noted and discredit the change message.

Inclusion of Checks and Balances and a Focus on Continuous Improvement

I defined innovation governance in the first article of this collection as a sort of ‘corporate constitution’ for innovation because it provides a frame for all innovation activities by defining the roles, powers and limits of the various players and by organizing the way all innovation-related processes work. Any constitution should provide its stakeholders with the correct level of checks and balances between the various power holders. And innovation governance is no different because it involves entrusting leaders or groups of leaders with special powers outside normal hierarchical relationships.

This, of course, depends on the organizational model the company has selected for allocating innovation responsibilities and the extent of the powers allocated to the chosen innovation leaders. For example, if CTOs or CIOs have been given a company-wide innovation governance mission, to what extent are they empowered to intervene in the business sphere of their corporate colleagues with whom they have no hierarchical relationships?

Checks and balances, in the case of innovation governance, deal with defining the roles and responsibilities of the innovation chiefs, their expected ways of operating in relation to their senior colleagues, and the right of recourse of these colleagues if they feel their leadership rights have been unduly encroached upon. In a company that we interviewed, the CIO is entitled to conduct a regular innovation performance audit of his colleagues’ business groups. But this review is jointly conducted by the Innovation Center controller and the business group controller. The idea is that both parties should reach a consensus. If there is disagreement, the issue is referred to the managing board, which receives every audit. The role of the top management team in that domain remains essential. C-suite members are the ones who ensure the proper level of checks and balances.

No company we know, even the most innovative, feels entirely satisfied with its innovation system. In fact, the more ‘advanced’ they are in their innovation management practices, the more demanding companies seem to be. This is why good innovation governance systems provide for a process of continuous improvement. This presupposes that:

- The company has started its innovation drive with a comprehensive audit of its various innovation activities and processes;

- This audit is repeated in an objective manner at regular intervals, ideally using industry-wide benchmarks; and

- The audit is communicated to top management and triggers a series of change programs by the responsible leaders.

Robustness of the Model vis-à-vis External Pressures and Crises

It is not uncommon to see companies embarking on a major innovation effort for a while, then to witness a substantial weakening of their focus and drive as soon as the first market or economic crisis appears. Under such circumstances, when it is not reducing the whole R&D program, management may typically cut innovation budgets and cancel longer-term or risky projects. These kinds of reactions are extremely detrimental to innovation activities that require steady, long-term investment and effort. They also send the message that, for top management, innovation is merely nice to have, not a must-have. This prevents people down the organization from making strong personal commitments to innovation and from taking risks. It is therefore essential to ensure that the innovation governance system is able to resist most of these short-term knee-jerk reactions when the company is confronted with crises.

It is therefore essential to ensure that the innovation governance system is able to resist most of these short-term knee-jerk reactions when the company is confronted with crises.

Management can take at least three measures to help the company’s innovation governance system resist this roller-coaster risk in the face of ups and downs in markets and economic cycles.

The first one is to ensure that the innovation system and budget are kept reasonably lean, even in favorable times, to avoid having to cut projects in bad times. This means, of course, paying a lot of attention to R&D budgets and the selection of new projects. It also implies avoiding devoting a lot of resources to full-time innovation management staff. Maintaining a lean central innovation staff is possible when the line organization is fully mobilized and participates actively in all innovation activities.

The second measure is to have one, or ideally several, high-level innovation advocates at the top management level. Of course, when the CEO is personally viewed as the ultimate corporate innovation champion, it helps in maintaining the focus on innovation in times of crisis. Strong CTOs or CIOs can also protect the company from drastic budget cuts; it all depends on their relative weight in the top management team, particularly vis-à-vis CFOs who, naturally, will call for cost-cutting.

The third measure is to isolate somewhat the innovation budgets of business units from the rest of their budgets to avoid across-the-board cuts in bad times. Business leaders who are often judged on their overall budget may be tempted to cancel longer-term activities to maintain short-term profits. Isolating innovation budgets – generally R&D expenditures –can be achieved by lumping true innovation projects into ‘multi-year programs’ that can be approved in that form by top management and separated officially from all other expenditures that are subject to classical performance evaluations.

Capacity of the Model to Evolve, Enlarge its Scope and Grow with the Company

Most if not all companies grow and evolve over time. Some do it rapidly, reaching billions of dollars in sales in a decade or less, others change more slowly. Some of them expand in terms of product range or diversify by entering completely new fields and creating new industries; others maintain the same product range but expand their geographical market coverage. Many change their structure over time as they create new business units and globalize their operations. Most have to adapt to the radical changes introduced through digital technology, internet and the emergence of social networks.

All these changes naturally affect the way innovation needs to be carried out, and hence governed. This means that an innovation governance model that is well suited to a particular company condition may not be adapted to the next stage in its development. This explains, at least in part – because changes in management also play a role – why many companies change their innovation governance model over time.

There are many different ways to adapt innovation governance to changes in the company’s condition and environment. Some companies may change models altogether, for example passing from a centralized model to a distributed one, or from relatively loose to much more structured governance. Other companies keep the same basic governance model but make it evolve to address their current challenge.

It is therefore important for management, as it regularly reviews its governance model, to assess whether the model it has chosen is expandable in terms of scope, product or geographical coverage, and to prepare for this evolution.

Clarity and Accessibility of the Governance Model for the Board of Directors

In the fourth article of this series, we advocated the need to keep the board of directors well informed of the company’s innovation governance philosophy, of its approach and of its chosen model to implement it. This is critical, particularly in companies for which innovation is a key growth driver. The board needs to understand how the company has organized its innovation efforts and what issues it is facing in order to exercise its dual management supervision role of supporting and challenging.

As part of his/her regular communication remit, the CEO should explain to the board the approach that he/she has chosen for innovation governance and the reasons for such a choice. This assumes of course that the model chosen by the company is clear in the minds of its top team, something that is not always the case. The board will naturally expect to hear how the CEO intends to be personally engaged behind the company’s innovation drive, even if overall responsibility has been entrusted to another senior leader or group of leaders.

Most boards have occasional access to the company’s senior leaders to hear about progress achieved in a number of important domains. It is therefore good practice to ask the innovation governance head(s) –the innovation-dedicated members of the top management team, the CTO, the CIO or the head of the innovation board, etc. –to present the results of the company’s innovation audit to the board at least once a year and discuss future issues. Board members are often deprived of such information and it would help them better understand the company’s strategy and outlook. They will naturally want to be reassured that management is properly aware of the strategic risks linked with either innovation myopia or misguided investments. The board could also challenge the CEO to upgrade the company’s innovation governance system if results do not meet its expectations.

In short, innovation performance and its drivers, as well as the company’s innovation governance organization, are items that should be put on the board’s agenda for information and regular discussions, alongside the other important strategic and organizational issues.

Auditing the Company’s Innovation Governance Activities

In discussing the role of top management with regard to innovation governance in the fifth article in this series, I suggested that the C-suite should regularly review the effectiveness of the company’s innovation system and model to improve it on a continuing basis. In the course of such regular reviews, members of the C-suite should take the time to explore together –honestly – how the company’s governance model meets these eight success factors before taking any corrective action that may be needed. We would suggest that each member of the top team should do this evaluation individually before sharing the results with one another. Individual evaluations should be used to launch discussions on the most commonly shared deficiencies and corresponding improvement opportunities.

The author wishes to thank Beebe Nelson, co-author of New Product Development for Dummies (Wiley Publishing Inc. 2007) for her contribution and improvement suggestions.

This article complements and ends the series of five articles on innovation governance published by InnovationManagement.se. These articles have been expanded and complemented with a number of real company examples of innovation governance models in a book to be published in the first quarter of 2014 by Wiley/Jossey-Bass. This book “Innovation Governance: How Top Management Organizes and Mobilizes for Innovation” is co-authored by Jean-Philippe Deschamps and Beebe Nelson.

About the author

Jean-Philippe Deschamps is emeritus Professor of Technology and Innovation Management at IMD in Lausanne (Switzerland). He has more than forty years of international experience in consulting and teaching on innovation. He was the co-author of Product Juggernauts: How Companies Mobilize to Generate a Stream of Market Winners (1995; Harvard Business School Press) and the author of Innovation Leaders: How Senior Executives Stimulate, Steer and Sustain Innovation (2008; Wiley/Jossey-Bass).

Jean-Philippe Deschamps is emeritus Professor of Technology and Innovation Management at IMD in Lausanne (Switzerland). He has more than forty years of international experience in consulting and teaching on innovation. He was the co-author of Product Juggernauts: How Companies Mobilize to Generate a Stream of Market Winners (1995; Harvard Business School Press) and the author of Innovation Leaders: How Senior Executives Stimulate, Steer and Sustain Innovation (2008; Wiley/Jossey-Bass).

Innovation Governance in Theory & Practice Collection:

- What is Innovation Governance? – Definition and Scope

- 9 Different Models in use for Innovation Governance

- Innovation Governance – How Well Does it Work?

- Governing Innovation in Practice – The Role of the Board of Directors

- Governing Innovation in Practice – The Role of Top Management

- → Imperatives for an Effective Innovation Governance System

- Innovation Governance: Why Should Top Management Care?

- 10 Best Board Practices on Innovation Governance – How Proactive is your Board?

Photo: Work at office from shutterstock.com