By: Altin Kadareja

As the economy is dynamically changing and innovation becomes crucially important, a look into the management practices and risks that such projects face should always be welcome. In part two of this series of articles focused on identifying risks on innovation projects, the attention will be directed towards the identification of the internal and hidden risks of innovation projects.

At the heart of both risk taking and innovation is the ability to adapt to change, to view change as opportunity rather than threat (Hogg, R.M. et al., 2005). However, what resembles as important is not risk taking but the effective risk management, from the very beginning of the project (Mortimer, 1995). Some studies have revealed new product acceptance as one of the most important innovation project’s failure reasons, reported to be from 40% to 90% across product categories (Cierpicki, Wright, & Sharp 2000; Griffin, 1997) in line with the uncertain innovation project activities and sector specificities (Pavitt, 1984; Dosi, 1988; Freeman, 1982). Others, such as the Executive Innovation survey (Andrew et al., 2009) have revealed risk averse corporate culture and lengthy development times, to be the two biggest forces holding down their return on innovation spending.

What is risk management in innovation projects and why is it different from a “regular” project?

What resembles as important is not risk taking but the effective risk management, from the very beginning of the project.

Now, some scholars think and evidence that the management of a “regular” project compared with an innovation project is consistently different (Goffin & Mitchell, 2005: 242) and that traditional project management techniques fail in managing such projects because of a decoupling between projects and their business environment (Shenhar & Dvir, 2007). This results in a gap between the organization’s management and the project teams, which too often have a sketchy view of the true business purposes for a project. In the same vein, innovation practitioners such as Joyce Wycoff, in an issue of the Innovation Network’s Heads Up¹, underlines the fact that innovation projects tend to start with loosely defined objectives which become clear only after a period of time and that the processes used are more experimental and seldom follow strict linear guidelines. She stresses as a crucial point the importance of teams dealing with risk management in failing fast and smart in order to move on to more attractive options.

Furthermore, particular efforts have been made to introduce new dimensions of risk identification and management. Floricel and Ibanescu (2008) have proposed the concept of dynamic risk as determinant of portfolio innovation management processes by arguing that various types of environmental dynamism impact differently the competitive advantage of firms and their capacity to anticipate the future, prompting firms to adopt different portfolio management processes to deal with the specific dynamics they face. Sitkin et al. (1992) have introduced another interesting dimension, the “level of control”. It refers to the ability of the innovation team to influence the course of action in such a way that a satisfactory solution can be realized within the project’s time and resource limits (Keizer and Halman, 2007). In a similar vein, Deloitte (2010) (a consultancy), has suggested the consideration of “the speed of onset”, which refers to the time it takes for a risk event to affect the business.

Therefore, risk management in innovation projects could be referred to as the management of an event that, if it occurs, adversely affects the ability of a project to achieve its outcome objectives (Garvey, 2008). Such objectives are usually considered as the project’s success parameters (Cozijnsen et al., 2000) that usually establish the degree to which an innovation project could be considered successful (De Leeuw, 1990), which varies within sectors, companies and even among different projects within the same firm (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997).

Successful parameters of innovation projects

The Department of Business and Regulatory Reform of UK lists out a number of guidelines of what could constitute a successful project (Department of BEER, Guidelines for Managing Projects, 2007), aggregated in three parameters: time, performance and cost (Lock, 2007), in other studies considered as: schedule, scope, and resources (Kendrick, 2003). Further research has outlined other quantifiable innovation project successful constraints such as: increased efficiency, higher productivity, increased turnover, etc. (Cozijnsen et al., 2000).

Taking into consideration these definitions, a successful innovation project should:

- be finished within the pre-established time limits (time);

- deliver the outcomes and benefits required by the organization, its partners and other stakeholders (performance);

- stay within financial budgets (costs).

As a result, every success parameter represents a venue of associated risk, in short: the extending of the time limits, dissatisfaction of consumer’s needs, exceeding of the planned budget (Lucia et al., 2008; Kendrick, 2003).

Every success parameter represents a venue of associated risk: the extending of the time limits, dissatisfaction of consumer’s needs, exceeding of the planned budget.

Following these macro venues of innovation project’s risks and the list of possible risks outlined by the Executive Innovation survey (Andrew et al., BCG, 2009), two separated risk clusters have been created: external and internal risks to the innovation project. External risks refer to the risks that the company can/does not fully control. They are related to factors external to the company, meaning coming mainly from its environment (Raftery, 1994). On the other hand, the internal risks represent the risks arising in innovation project’s activities within the project/company (Raftery, 1994).

In addition, given the traditional approaches to manage risks will ignore the underlying attitudes and behaviors that influence the willingness and comfort of the management with higher risk levels in innovation projects (Kumar & Singh, 2006), I have identified and investigated the hidden risks. Those risks that are usually unknown as the project starts and only after a period of time become visible. To do this, the surveyed firms were asked to identify the risks of both successful and non-successful innovation projects. Therefore, risks which have been identified as barriers to successful innovation projects are likely to be considered as risks with a “controllable” probability and impact value, and risks which have been identified as barriers to non-successful innovation projects are likely to be considered as risks with high probability and impact value. While the difference between the two will determine the hidden risks of innovation projects.

Internal and hidden risks of innovation projects

In table 4, the results (using the methodology explained in the notes) of internal risks of innovation projects for both cases: successful and non-successful have been summarized.

Referring to the risks of successful innovation projects, “Time risk” and “Risk-averse culture” appear to be the two most internal significant risks. Whereas, the least barriers for the successful innovation projects have been “Leadership support” and “Personnel risk”.

On the other side, for the non-successful innovation project’s internal risks, the two most significant risks have switched places. “Risk-averse culture” becomes more relevant and influential on the success rate of innovation projects than “Time risk”. Interestingly, the two second most important risks on those innovation projects which have been non-successful, have been “Leadership support” and “Customer Insight Risk”.

“Time risk” and “Risk-averse culture” appear to be the two most internal significant risks.

Fig a.4 summarizes the analysis of the hidden risks, those risks that have highly influenced a project to become non-successful. That is, the difference between the risk value of the weighted mean score of the non-successful and successful innovation projects.

“Leadership support”, “Customer insight risk” and “Marketing risks” appear to be the most significant hidden innovation project’s risks. Indeed, if the innovation project lacks the leadership support or customer insight, it has high chances of failing. On the other side, time risk is the least hidden. It has scored the same weighted mean in both analysis, successful and non-successful, that is, time risk remains the biggest internal “certain” risk of innovation projects.

In conclusion, an innovation project could be considered successful if the project is finished within the pre-established time limits (time), has delivered the outcomes and benefits required by the organization, its partners and other stakeholders (performance), and stayed within financial budgets (costs). Such projects, will probably face the following most dominant internal risks:

- “Risk – averse culture”;

- “Lengthy development times”;

- “Not enough customer insight”;

- “Insufficient support from leadership and management”.

Particular attention should be directed towards “Leadership support” and “Customer insight risk” as the two biggest hidden risks influencing a project to become non-successful.

Particular attention should be directed towards “Leadership support” and “Customer insight risk” as the two biggest hidden risks influencing a project to become non-successful. Therefore, more efforts should be directed toward the mitigation activities of such risks before the project starts. Managers should ensure the full leadership support and complete understanding of customers on the innovation project that they are launching.

Methodology

In the following paragraphs, I will illustrate the methodology that has been used for obtaining the previous results. The same approach has been used for the articles to follow.

A survey has been developed and distributed to the targeted companies. Descriptive and inferential statistical analysis have been used on the answers provided. Firms were asked to indicate on a five point Likert scale – from 1 (small risk) up to 5 (large risk), the potential internal and external risks to innovation projects. A total of 36 firms have responded, 65 percent of 55 firms that were initially contacted. Of the returned questionnaires, 4 could not be processed so the final number of respondents was 32, managing a total of 1690 innovation projects within a five years period of time (2005-2009). In table 1, a summary of the general characteristics of the surveyed firms is presented.

However, survey-based studies might not correctly estimate the required result of the analysis given the response biasness due to the fact that the assessment of project’s success was left to the surveyed firms (Gourville. T. J, 2005). A formula weighting the manager’s (firm) experience in managing innovation projects, along two variables: number of innovation projects and the success rate on those project, has been used. That is, the higher the number of projects the firm has managed for the time period in analysis, the bigger the experience the innovation manager embeds and can further share in the company (experience). On the other side, the more successful the innovation manager has been on the projects managed the more important its relevant experience (success).

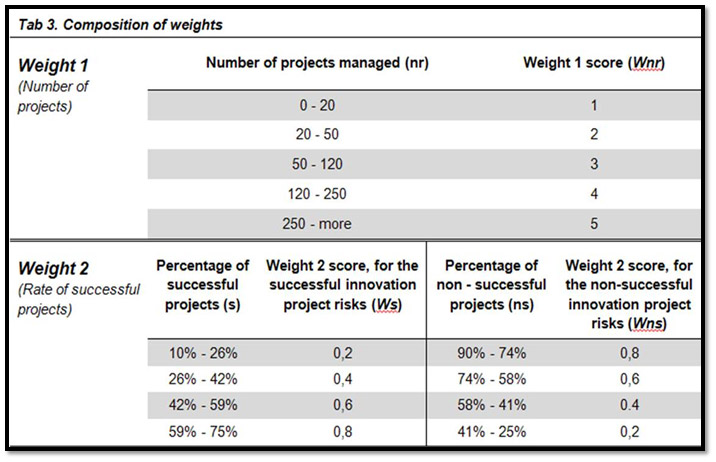

In this context, in order to overcome the response biasness problem, a higher value to the magnitude of experience (number of projects managed) was given weighting it with a score level from 1 to 5, than to better experience (percentage of successful innovation projects) weighting it with a score level from 0.2 to 0.8.

Therefore, the first weight (Weight 1 = Wnr) referring to the absolute number of innovation projects has clustered the firms into five different classes (table 3). The second weight (Weight 2 = Ws/Wns) referring to the rate of success on innovation projects has created four different classes, from a success rate in innovation projects of 10 percent (minimum reported value) to 75 percent (maximum reported value).

Therefore, using the parameters as calculated above and explained in table 3.1, this has been the formula used for the calculation of the risk’s weighted mean score for both cases: Successful and Non-Successful innovation projects.

Successful Innovation project’s risks weighed mean score:

| WR = f(nr, s, V) |

|

WR = (Wnr + Ws)*V |

For instance, if one firm has been responsible for 80 projects with an average success rate of 20 percent, it has scored 3 in the first weight (Wnr) (tab. 3) and 0,2 in the second weight (Ws) (tab.3), generating an overall weighted score of 3,2. Next, this weight has been multiplied with the variable risk score. Thus, if the firm has indicated “risk – averse culture” for the successful projects as one of the biggest barriers to such innovation projects and has reported a risk score of 5, the overall risk’s weighted mean score for this particular risk for the successful projects has been:

WR (Weighted mean risk score) = (3 + 0,2)*5 = 16

Non-Successful Innovation project’s risks weighed mean score:

| WR = f(nr, ns, V) |

|

WR = (Wnr + Wns)*V |

In the same vein, when measuring the risks that have made the project non-successful, the only difference has been the second weight applied (Wns). Using the same example as before: If the firm has been responsible for 80 projects with an average success rate of 20 per cent, it has scored 3 in the first weight (Wnr) (tab.3) and 0,6 in the second weight (Wns) (tab.3), generating an overall weighted score of 3,6. And, if the firm has indicated the same “risk – averse culture” for the non-successful projects, as well as one of the biggest barriers to such innovation projects and has reported a risk score of 5, the overall risk’s weighted mean score for the non-successful projects has been:

WR (Weighted mean risk score) = (3 + 0,6)*5 = 18

Therefore, for the same firm with the same experience (the number of projects managed), the related risk “risk-averse culture” even though for the firm has had the same level of significance, for the analysis has resulted in a different significance level. This, due to a different weighted mean scores associated to an alteration of the success rate in the innovation projects of this firm.

In the same vein, it could be controlled for the impact of the first weight in the final risk’s weighted mean scores recognizing the difference in the amplitude of such impact given the dissimilarity of the importance that every weight has accounted for this analysis.

More articles in this series:

Part 1: What drives a Successful Innovation Eco-System

→ Part 2: Internal and Hidden Risks of Innovation Projects

Part 3: External Risks of Innovation Projects

Part 4: Risks of Incremental, Differential, Radical, and Breakthrough Innovation Project

About the author

Altin Kadareja, MSc, passionate about innovation management has experimented several risk management techniques in innovation projects in Italian banks. Holds a Master of Science degree in Economics and Management of Innovation and Technology from Bocconi University, Milan. Former organizational change consultant focusing on business process re-engineering. An amateur entrepreneur, already founded a start-up and an economic think tank.

Altin Kadareja, MSc, passionate about innovation management has experimented several risk management techniques in innovation projects in Italian banks. Holds a Master of Science degree in Economics and Management of Innovation and Technology from Bocconi University, Milan. Former organizational change consultant focusing on business process re-engineering. An amateur entrepreneur, already founded a start-up and an economic think tank.

References

Andrew, P. J. et al. (2009), “Innovation 2009 – Making hard decision in the downturn, A Boston Consulting group senior management survey”, Boston Consulting Group, available at: http://www.bcg.com/documents/file15481.pdf (accessed 5 October 2010).

Brown, S.L. and Eisenhardt, K.M. (1997), “The art of continuous change: linking complexity theory and time-paced evolution in relentlessly shifting organizations”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 42 No. 1, pp. 1-34.

Cierpicki, S., Malcolm W. and Byron, S. (2000), “Managers’ Knowledge of Marketing Principles: The Case of New Product Development,” Journal of Empirical Generalizations in Marketing Science, Vol. 5, pp. 771-790.

Cozijnsen, A. J., Vrakking J. W. and IJzerloo V. M (2000), “Success and failure of 50 innovation projects in Dutch companies”, European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 3 No. 3, pg 150-159.

De Leeuw, A.C.J. (1990), “Besturen van veranderingsprocessen: Fundamenteel en praktijkgericht management van organisatieveranderingen“ Alphen aan den Rijn, Samsom.

Deloitte. (2010), “Risk Intelligence in a downturn: Balancing risk and reward in volatile times”, Risk Intelligence Series, Issue No. 14, (accessed 14 September 2010)

Dosi, G. (1988), The nature of the innovation process: Technical Change and Economic Theory, Brighton, U.K.

Floricel, S and Ibanescu, M. (2008), “Using R&D portfolio management to deal with Dynamic Risk”, R&D Management, Vol. 38 No. 5, pp. 452-467.

Freeman, C. (1982), The economics of industrial innovation, Pinter, London.