In part one of this two part series on how to measure open innovation, we examined three distinct principles that companies must consider to successfully set up a metrics-based performance measurement system for their open innovation projects:

- Use unique metrics for each open innovation method

- Consider different types of measures (input, process, output, outcome)

- Think about how to effectively utilize your open innovation metrics

The power of this deceptively simple framework lies in the integrity of its different KPI dimensions. Only the combination of input, process, output, and outcome metrics (principle 2), which precisely fit to a specific open innovation method (principle 1), while following a suitable type of utilization (principle 3) will help you choosing the right measures for your open innovation project.

Even though we proposed a first approach of how we should look at open innovation metrics, there is still no answer on what we should actually measure. What are the relevant key performance indicators behind that framework? Answering this question was the motivation for our Open Innovation KPI 2012 study.

Methodology

By following the framework mentioned above, we first had to decide which of the existing methods and tools for integrating external knowledge into the open innovation process should be applied to our performance measurement toolkit (principle 1). It is important to note that our research focus is on “inbound open innovation”, which implies the integration of external ideas and technologies into a company’s own innovation process. The transfer and commercialization of unused, internally developed ideas and assets in an external market is a mode called “outbound open innovation”, which is, however, not a subject of this study. At the end of an extensive analysis and careful consideration of many open innovation methodologies, the decision was made to take a closer look at the three most prominent methods of “inbound open innovation” (lead user method, ideation contest, and broadcast search). All of which cover both the various early stages as well as the later stages of the innovation process. For a brief introduction of the methods and techniques applied to our performance measurement toolkit, please see the first article of this series.

Afterwards, the framework has been enriched with a number of meaningful performance measures for each open innovation method. Experimental data sets from different sources and theories were used to collect the most reliable metrics. After reviewing numerous studies indicating critical success factors (CSFs) for an effective implementation of open innovation, we identified the most relevant CSFs for each considered OI method and determined a range of ”winning KPIs”, as they have been derived independently from the CSFs. Besides our study on critical success factors, whose relevance is mainly on the academic site of research, we also drilled down into a few industry case studies (e.g. 3M, SAP) of companies that have already started to adapt their measurement tools to the new concepts and challenges of open innovation. The published results of these studies and relevant lists of open innovation metrics served as supporting data sources for the subsequent development of a first version of a literature-based performance measurement system.

So far, however, there was no indication that the information and metrics collected from literature would provide a wide range of application for practical decision making in business corporations.

In order to close this gap, experts from corporate functions and management consulting were asked to participate in a survey to assess the relevance of an assembled set of key performance indicators. Another survey question explored how these metrics are being used to monitor the performance and predict the return of their open innovation projects.

The survey was conducted by EY (Ernst & Young) in cooperation with the Technology and Innovation Management Group at RWTH Aachen University, Germany, aimed to identify the most relevant key performance indicators for measuring open innovation.

Survey Design and Data

Innovation practitioners and international consultants share a slightly different opinion on how to best apply metrics to open innovation

To perform a quantitative study on how to measure open innovation in mid-sized and large firms we invited over 75 senior executives responsible for innovation management, corporate development, R&D, performance measurement, and marketing of large and stock market listed firms in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria as well as 588 senior finance consultants of the EY global network to complete an online questionnaire on our website.

The survey was divided into two parts: First, the participants were asked to indicate the relevance of a given set of open innovation measures and how they would use (instrumentally, conceptually, or symbolic) these metrics in order to analyze the success of an OI campaign. Second, they rated how important they perceive each provided KPI as part of a performance management toolkit to measure and control the innovation success of a specific open innovation method.

Our sample included large companies of different industries (e.g. chemical and pharmaceutical, automotive and mechanical engineering, consumer goods, professional services) with revenues annually in excess of more than EUR 200 million and more than 1,000 employees. 40 % of the participants were listed in the German stock market (DAX), representing the 30 largest companies in Germany. We received usable responses from 117 industry practitioners and consultants. In the following, we share some of the key results of our study. For additional information on the results and the research methodology please feel free to contact us.

Making Better Use of Metrics to Drive Improvement in Open Innovation Projects

The study’s first question explored how metrics are being used by both practitioners and consultants to monitor the performance and predict the return of their open innovation projects. As already mentioned in part one, metrics can be utilized on three different levels: instrumental, conceptual and symbolic.

- Instrumental use refers to the application of information/metrics utilized directly for decision making.

- A more indirect use is the conceptual one. The use of the information/metric does not directly lead to a concrete action, but rather provides general enlightenment and understanding.

- Metrics can also be used after decisions have already been taken to legitimize and justify them. This kind of use is called symbolic.

As shown in Figure 2, the indicators of open innovation were seen to function most in conceptual roles, helping decision makers to challenge the status quo and to support alternative thinking and new innovative concepts. Given their role in shaping opinions, the conceptual use of metrics relates less directly to the pure input of knowledge into immediate decision making and has more to do with identifying and bringing problems into consideration.

A closer look at our two different sample groups indicates that experienced innovation practitioners and international consultants share a slightly different opinion on how to best apply metrics to open innovation. 39% percent of the EY consultants reported that decisions should be made directly on the basis of an indicator score (instrumental use), while almost the same proportion of innovation managers rather use metrics tactically or symbolically to delay or spur action on an open innovation issue by undercutting or supporting existing or proposed decisions.

To some extent, this difference in focus should be reflected in different interests and perspectives of stakeholder groups:

The pure instrumental use of metrics seems to be rather the exception than the rule in business corporations

Innovation managers tend to assume that their open innovation projects are subject to significant uncertainty and largely unforeseen pathways, particularly in the early stages of development; thus, for them, concrete targets and measures don’t seem to be definable or detectable. When looking for radical innovations, it seems to be even more difficult to measure the basis of a complex decision. Just the same, if all factors influencing the decision could not be collected; accurate metrics for a pure instrumental use might seem untraceable. For them, non-instrumental uses of indicators are important in their own right, and that indicators can play an essential role in framing problems conceptually or reinforcing political decision on open innovation. According to these findings, namely that the “pure instrumental use” of metrics seems to be rather the exception than the rule in business corporations, one of the participating innovation managers made the following comment:

“The most important thing of open innovation is the new way of thinking. What is important is that both partners perceive the support they get from each other as ambivalent. That takes a lot of time, and it implies that those who do a lot of experimentation will automatically make mistakes compared to those who are more reserved. Therefore, metrics play a politicized role more often than an instrumental role.”

Consultants, in turn, frequently experience the problem that many innovation projects are getting out of control, because no or too few suitable measures have been determined in advance; and in most cases exceeding, for example, in time and cost requirements won’t also lead to serious restrictions. That fact gives rise to a more instrumental use of metrics where generated data is incorporated directly into the decision making processes in a transparent way that leads to improved results.

To get an even more detailed understanding on the current status of indicator usage in open innovation, we also explored the primary role that metrics play when tracking different types of measures.

Looking across the different types of indicators the instrumental role seems to be more prominent at the very beginning (input) and at the end of the performance measurement process (outcome), while conceptual and political roles dominate output measures (see Figure 3). Obviously, measures of human or financial inputs and outcome indicators that determine the value of an innovation are much more meaningful and suitable to incorporate directly in decision making processes rather than measures that have not yet been completed intermediate results such as the number of ideas generated through open innovation. Thus, 78 % of all survey participants might not base their decisions on non-financial output measures. To them, output measures rather represent particular ways either to conceptualize problems and solutions or to legitimize (or delegitimize) decisions for tactical reasons.

Measures for Open Innovation – Are There Any Suitable Measures?

Consultants attach a higher relevance to metrics than practitioners

To investigate the usefulness of different metrics for measuring open innovation, we provided our respondents with an assembled set of key performance indicators for each open innovation method. We measured their relevance by probing the respondents to assess how important they perceive these measures on scale from 1 (very unimportant) to 5 (very important). Figure 4 aggregates the results across the different types of indicators. All indicators address the input, the process, the output, or outcome of open innovation.

The results illustrate that generally speaking industry firms and management consultants view these indicators as basically important (a score of 3 represents a neutral point view). Thus, they are somewhat confident that these measures are getting it right and helping firms to improve their open innovation activities.

However, it turns out that, on average, consultants attach a higher relevance to metrics than practitioners. The reasons behind this preference seems to be very similar to the different behaviors between the answers of both target groups whether metrics should take an instrumental, conceptual or more symbolic/political usage. While consultants tend to come up with sophisticated performance measurement concepts in order to control the apparently uncontrollable for their clients, many practitioners (and innovators respectively) still argue that too much measurement stifles innovation. In this context, one of the practitioners claimed:

“The journey is its own reward – What comes out doesn’t count until the second step. First, it is important to be able to accept other points of views, to spot external sources, and to integrate…”

In general, however, respondents seem to have a stronger tendency towards financial outcome measures, and prefer those indicators less, which by nature are more difficult to attract. We found that most widespread measures where firms, on average, show a very positive tendency are those that serve as a basis for an effective sales and profit planning. Interestingly, measures that relate to an economic outturn seem to be more promising than measures that address empirically proven critical success factors of open innovation. Why is it not common to integrate prevailing empirically validated open innovation enabler as part of a performance measurement system?

A first reason is that the new methods of open innovation are relatively young and still maturing. The ‘old’ systems that set out to measure innovation are, at best, slightly adjusted to external influences, but do not capture or quantify critical success factors of open innovation. Another reason could be that outcome measures are usually more meaningful than high-risk intermediate results such as first solution approaches or intangible ideas. Qualitative indicators such as the radicalism and novelty of ideas are hard to attract since they have to be collected through painstaking qualitative assessment procedures.

Open Innovation Scorecards – What Are The Most Important Measures?

A performance indicator is a quantitative analytical tool that needs to be easy to measure – some metrics appear subjective and difficult to measure.

As our survey reveals, many metrics might seem right and easy to measure. Other metrics are more difficult to measure, but focus the enterprise on those decisions and actions that are critical to success. So what, are we now supposed to look at or measure when determining if an open innovation campaign is successful or not?

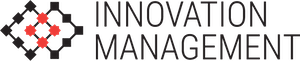

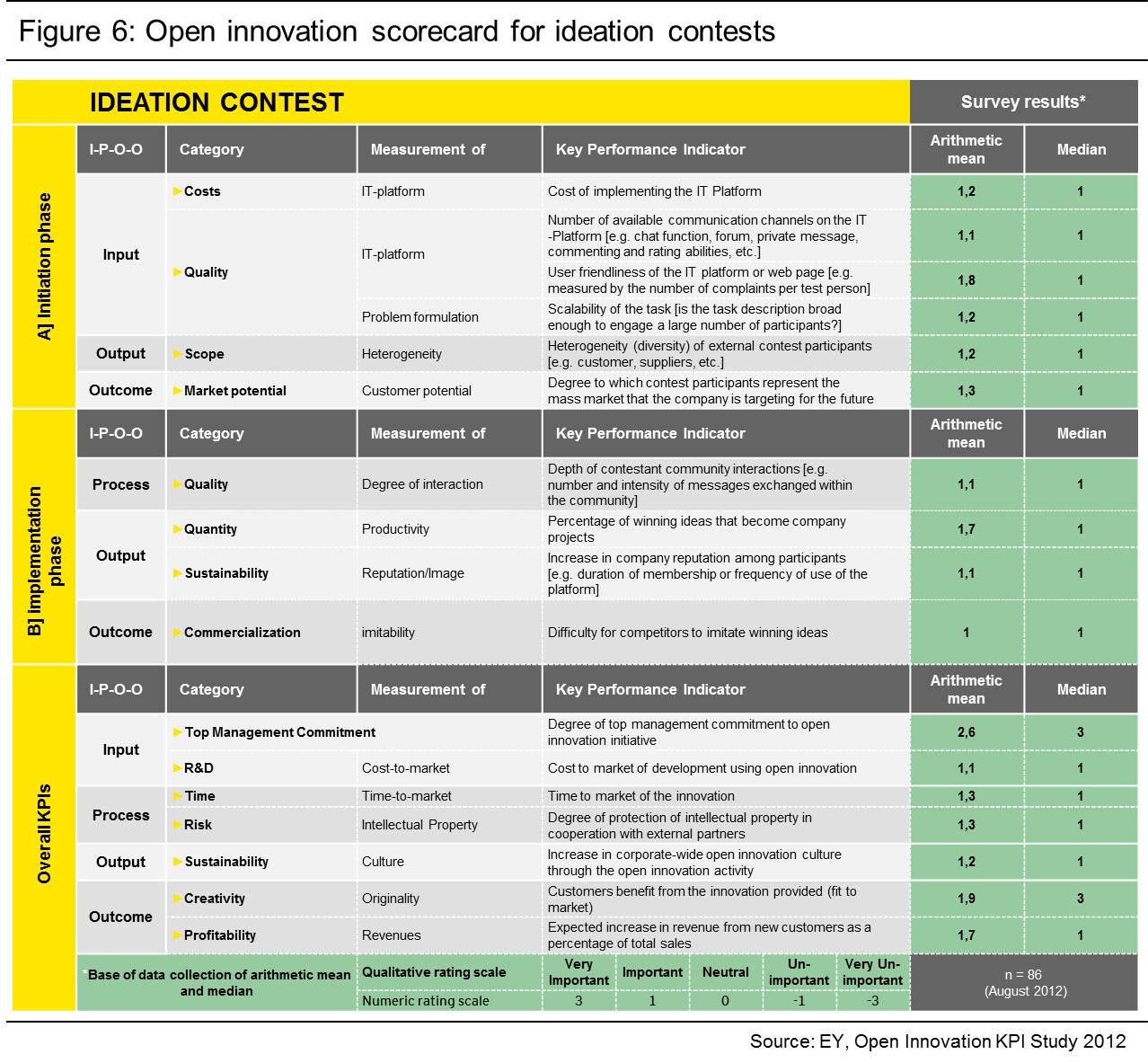

By analyzing the survey results, we were able to reduce the initial amount of indicators to reach a much smaller though statistically significant set of metrics for each open innovation method. Only those measures that received a mean and median score of 1 or above on a bipolar scale where -3 means very unimportant, 1 means important, and 3 means very important became part of our so called open innovation scorecards. This allowed us to subsequently narrow down the initial lists of potential measures by more than 40 % to the most important ones.

In order to help organizations identify and determine a coherent portfolio of right metrics directly associated to their open innovation strategy, we propose the following three open innovation scorecards. These scorecards were created based on our three key principles on how to measure open innovation (see Figure 1) and represent the highest priority measures selected by our survey respondents.

Brief explanation and takeaways:

Output measures seem to be relatively less promising than measures that relate to an economic outcome

On average, we observe, that all of these metrics taken from literature play an important role in measuring the success of a lead user project. It turns out, that the lead user method is a very complex method, which requires more than just a few indicators. Output measures seem to be relatively less promising than measures that relate to an economic outcome. On the other end, firms seem to have the strongest tendency towards metrics that relate on an input and outcome perspective at all stages of the open innovation method (initiation and implementation phase). However, indicators that are used to measure the process efficiency of transforming inputs into outputs are rated lowest in importance. We also learned that input and outcome indicators follow a more instrumental usage.

Brief explanation and takeaways:

On average, we observe, that all of these metrics taken from literature play an important role in measuring the success of an ideation contest. It turns out, that the ideation contest is sort of a complex method, which requires more than just a few indicators. To our experts, output measures seem to be relatively less promising. However, measures that aim to determine the value of an innovation in terms of outcome KPIs are significantly important throughout the entire stages of the open innovation method (initiation and implementation phase). Interestingly, only input measures that appear at the initiation phase scored significantly high. On the other end, indicators that are used to measure process efficiency of transforming inputs into outputs are rated lowest in importance. We also learned that input and outcome indicators follow a more instrumental usage.

Brief explanation and takeaways:

On average, we observe, that all of these metrics taken from literature play an important role in measuring the success of broadcast search. It turns out, that broadcast search is sort of a complex method, which requires more than just a few indicators. To our experts, output measures seem to be relatively less promising during the implementation phase of a broadcast search. Interestingly, input and outcome measures that appear at the initiation phase are considered to be of low importance, since they do not show up in our scorecard. Indicators that are used to measure process efficiency of transforming inputs into outputs are rated lowest in importance. We also learned that input and outcome indicators follow a more instrumental usage.

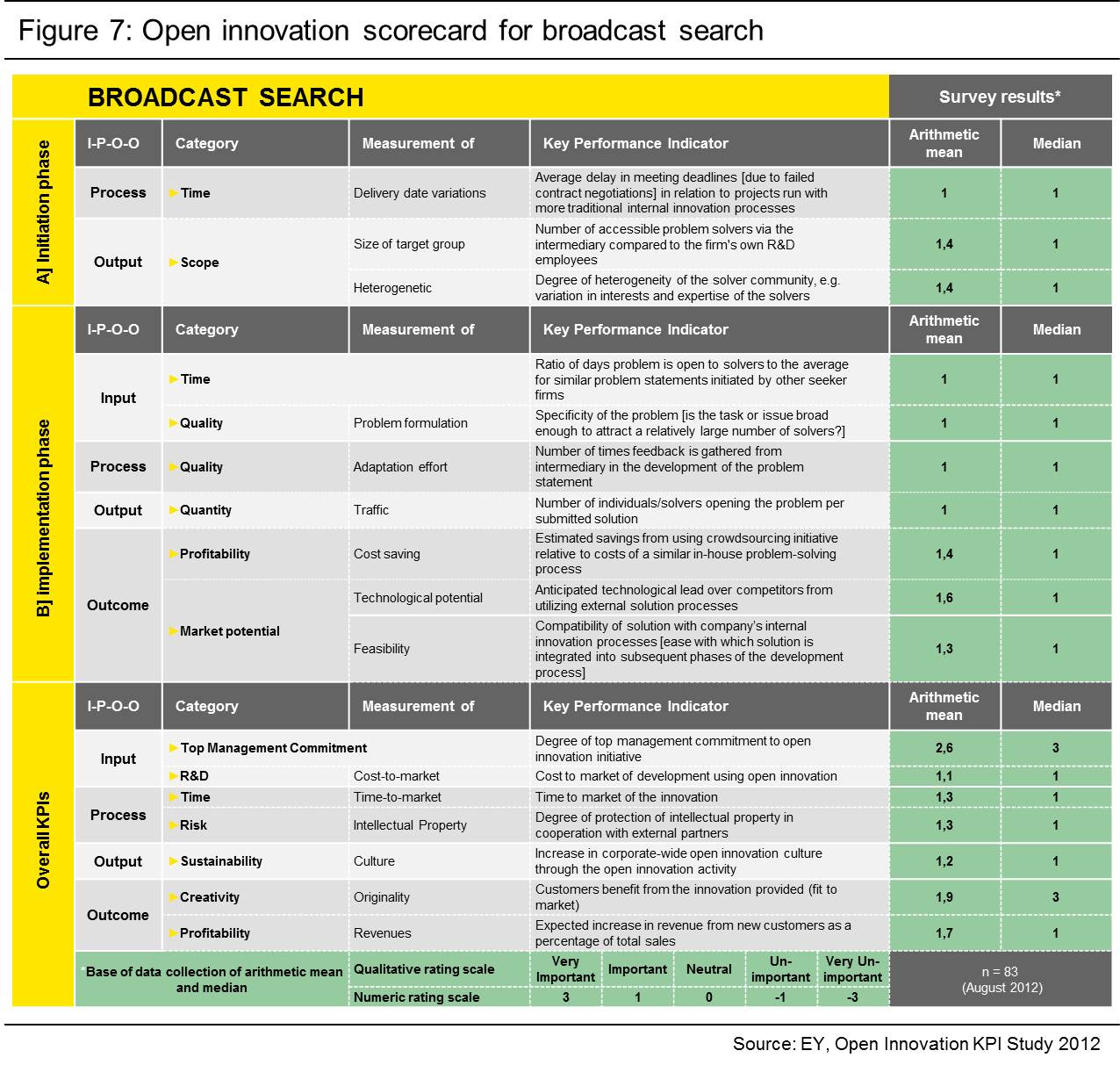

A Process Oriented Point of View

When looking at it from a process perspective, the developed open innovation scorecards can be applied to the different phases of the innovation process as follows: in the early stages, both the lead user method and idea contest are helpful tools for identifying customer needs and first solution approaches. Broadcast search, however, is particularly useful in later stages of the innovation process to generate suitable knowledge for technological solutions or to identify potential solution providers. Depending on the chosen method, the individual scorecards can then be used to monitor and predict the success of the open innovation campaign.

Conclusion

Open innovation is not an automatic success but one that demands appropriate tools and metrics that enable you to change your strategy before mistakes become expensive or great ideas are refused. To this end, a performance measurement toolkit exists, empowering decision makers and innovation teams – especially in technology-based industries – to properly assess, control, and measure the performance of their open innovation activities.

Contrary to many other OI indicator studies, a toolkit has, in this case, been realized, not only in terms of secondary data sources, but also through an empirically evaluation. This allowed us to reduce the initial amount of indicators to reach a much smaller though statistically significant set of relevant metrics provided by our three scorecards for each open innovation method. Thus, these scorecards might help you to identify and determine a coherent portfolio of right metrics directly associated to your open innovation strategy as they reflect only those measures that were rated significantly important by almost 90 innovation experts and consultants.

Afterwards, the identified measures have to be utilized or initiated by the responsible actors within your company. As our study reveals, input and outcome measures should rather follow an instrumental use, while output and process KPIs were dominated by a conceptual use.

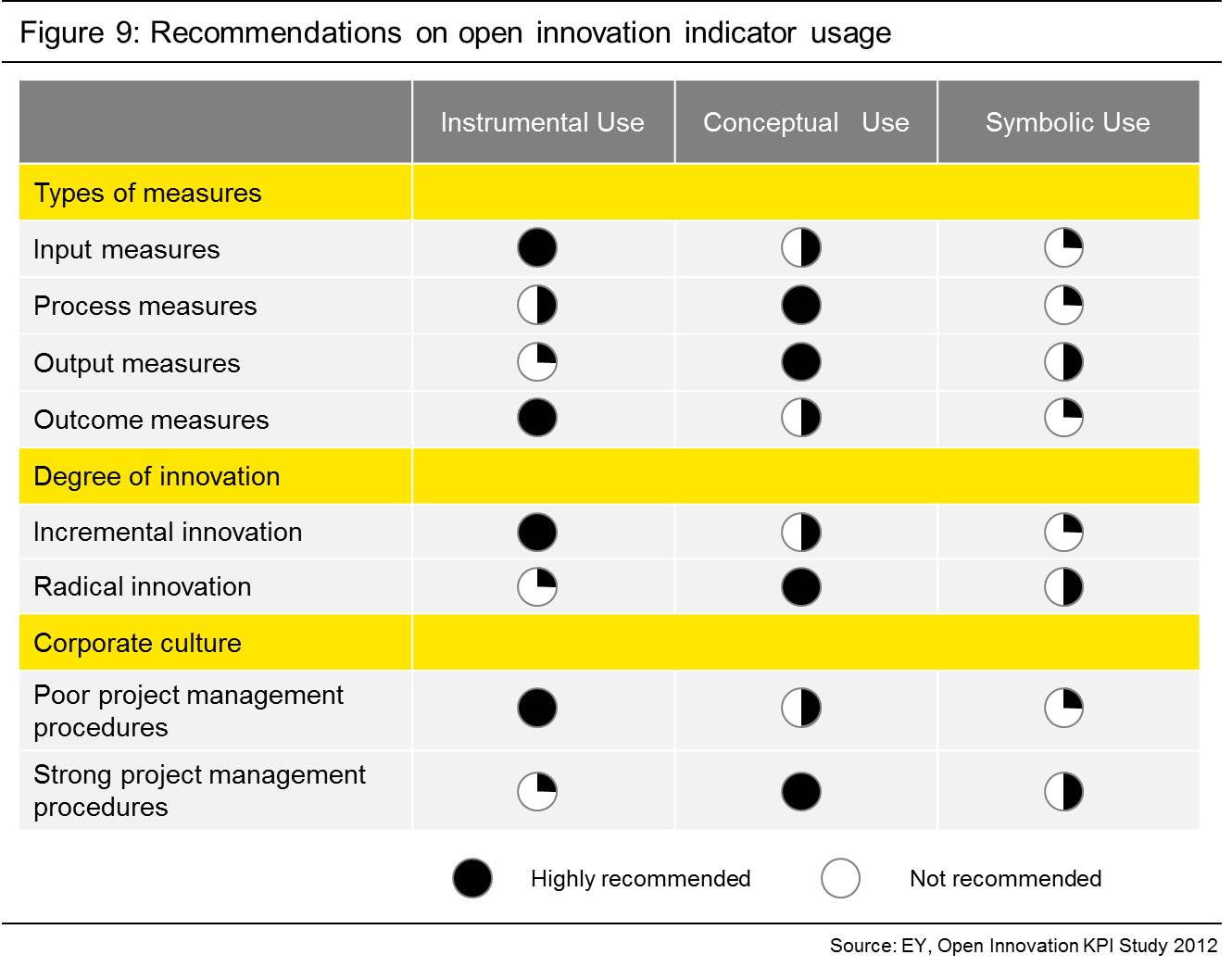

However, a successful application of indicators also depends on the innovation challenge (degree of innovation) as well as on a company’s ability and sincerity to appropriately plan and manage an open innovation campaign (corporate culture). A dedicated focus on increasing radical innovation should involve a conceptual use of open innovation metrics. Nevertheless, if companies tend to lax treatments concerning deadlines and budget increasingly, then an instrumental use of measures is recommended. The chart below summarizes our recommendations on indicator usage based on the findings of our survey.

About the authors

Marc Erkens is a strategy and innovation consultant within the Performance Improvement department at EY’s (Ernst & Young) Advisory. Passionate about innovation, Marc supports large German companies and multinationals to improve their capabilities in innovation management. There, he specializes on open innovation controlling and the selection and integration of appropriate open innovation tools to stimulate companies’ innovation success with the focus on new business models. Prior to joining EY, Marc was a student research assistant at the Technology and Innovation Management Group at RWTH Aachen University, where he received a master’s degree in economics.

Susanne Wosch Susanne is a Senior Manager within the Performance Improvement department at EY’s (Ernst & Young) Advisory focusing on strategy and innovation consulting services. Based on her scientific background and more than ten years of professional experience as part of EY’s European Life Sciences Center she has a strong preference to serve clients of the life science industry (pharma, biotech, medtech). Susanne is in charge for EY’s innovation management services within the life science industry sector. There, she focuses on Business Model Innovation, Open Innovation and the evaluation of innovation activities. Before joining EY, Susanne studied biochemistry and obtained a PhD in neurology.

Dirk Lüttgens Dirk Lüttgens is an assistant professor at the Technology & Innovation Management Group at RWTH Aachen University. He also is a consulting team member at Competivation where he is responsible for the scientific link between Competivation and RWTH TIM. He has over ten years experience as a project manager in technology and innovation management and received his PhD on innovation networks. At the Chair of Technology and Innovation Management, he heads the areas of open innovation for technical problem solving, service innovation, and innovation process design. As a consultant, Dirk supports particular companies in the machinery and plant engineering in the implementation of innovation processes, the selection of appropriate innovation tools and the design of an innovative corporate culture.

Frank Piller is a chair professor of management and the director of the Technology & Innovation Management Group at RWTH Aachen University. He also is a founding faculty member and the co-director of the MIT Smart Customization Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA. Frequently quoted in The New York Times, The Economist, and Business Week, amongst others, Frank is regarded as one of the leading experts on mass customization, personalization, and open innovation. Frank’s recent research focuses on innovation interfaces: How can organizations increase innovation success by designing and managing better interfaces within their organization and with external actors.

Photo: Set of tools over a wood panel on black and white from shutterstock.com