By: Doug Collins

Organizations that pursue the inquiry-led form of collaborative innovation often have an outcome in mind. They may seek the “low-hanging fruit” of immediately actionable ideas. They may seek ideas that help to re-envision the business. In this article innovation architect Doug Collins reflects on how the savvy practitioner manages the challenge question formation process to help the sponsor achieve their desired goals. The key? Knowing how to dial up and dial back the level of transformation incumbent within each question.

Come, Be A Man to Me

A family friend gave our infant daughter the gift of a CD of nursery songs. The music is nice: an acoustical guitar accompanies a woman singing folksy tunes.

I discovered that I had misheard the lyrics to one of the songs. The correct words…

Come be a mel-, be a mel-o-dy.

The singer invites the listener to join her in song.

I heard…

Clients ask me if there is a “right” question to pose to the crowd.

Come be a man, be a man to me.

We listen to the CD on lazy Saturday mornings over coffee and cream of wheat. As the song would play, three competing thoughts would, unbidden, enter my head.

- Thought one: The song seems wildly inappropriate for a children’s CD. Can I be hearing the song correctly? Do I raise the alarm?

- Thought two: Does the pleasingly melodic nature of the song excuse the lyrics? Had the producers done the moral calculus and concluded the same, freeing them to give the track a green light?

- Thought three: Had I missed a long-held, if obscure, practice of introducing adult themes to children through song? Folk singing might be a lonely profession.

Reading the liner notes clarified matters for me.

This instance of my mishearing lyrics (a wonderfully common occurrence for me) comes to mind when I talk to clients about challenge question formation: specifically, how two or more questions, pointed at the same topic, can elicit from the community vastly different responses.

And, how half the time, the intended audience misreads the intent. One can make a strong case for pre-testing questions if they assume people like me, with a gift for misinterpreting, are in the crowd, waiting to apply our own delusional meanings to otherwise rational questions.

The Secret Handshake for Crowdsourcing

Clients ask me if there is a “right” question to pose to the crowd. If so, would I be so kind as to share the secret handshake?

My response: no. In fact, I would argue that there are an infinite number of “right” ways to ask a challenge question. The trick—the handshake—is to align your question with your intent and to seek the right level of transformation.

The following is an example of the latter: let us say that you work for a company that makes hand soap. You wish to convene a community on a product improvement challenge. A perfectly fine, basic challenge question might be…

How might we, through washing, minimize the bacteria people have on their hands?

This sort of question might lead to all sorts of ideas around new product formulations and methods.

Consider, by comparison, the following version:

How might we minimize the rate of transference of transmittable disease in the home?

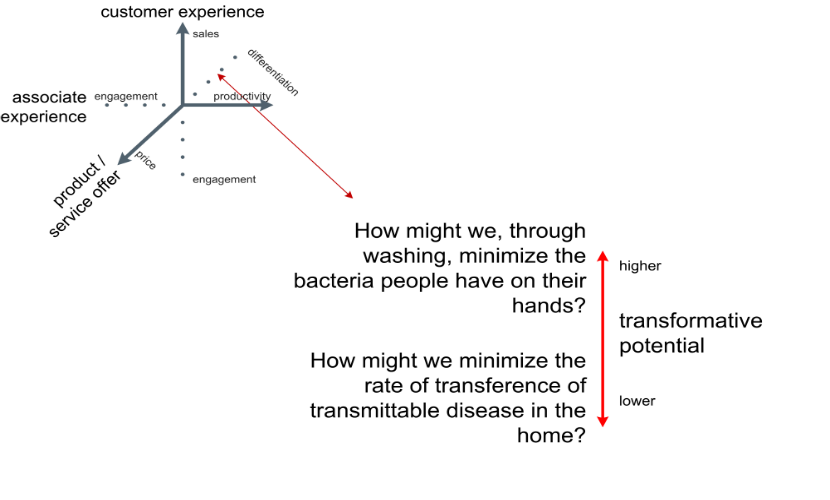

The second variation is not inherently superior to the first. It does, however, hold the potential for greater transformation (figure 1).

Why? The anchor point for the second variation moves beyond the means (i.e. washing one’s hands) to the ends (i.e., reduce transmission of disease).

Context matters. When your organization seeks “the low hanging fruit” from the practice of collaborative innovation, dial back the level of transformative potential of the question. Doing so keeps the community from swinging for the fences when the sponsor desires singles and doubles (apologies: American baseball analogy).

A Practitioner’s Tip on Innovation Management

Practitioners apply one part art and one part science to challenge question formation. When facilitating sessions around this topic—how to arrive at the question that most aligns with intent, I sometimes introduce the concept of anchor points to the challenge team (figure 2).

To continue with the soap example, I might write on the whiteboard a list of words that move from the means of the inquiry (bottom of the list) the ends of the inquiry (top of the list). That is, the soap company ultimately seeks to provide its consumers with greater happiness because they spend less time being sick from having caught transmittable diseases (e.g., diseases caught by shaking unwashed hands).

The anchor points can then serve as a way for the challenge team to begin to form their questions as an exercise. It’s a fascinating part of the work to see how each challenge team member approaches the question with relation to the anchor point that resonates with them. Where do they sit on the transformative scale?

In closing, do not allow yourself the indulgence of believing you heard one point of emphasis when in fact another is expected or desired. Do not seek a man when what is needed is a melody.

By : Doug Collins

About the author

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations such as The Estee Lauder Companies, Jarden Corporation, Johnson & Johnson, The Procter & Gamble Company, and Ryder System navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation. Doug develops approaches, creates forums, and structures engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the ideas and to the collaboration that result.

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations such as The Estee Lauder Companies, Jarden Corporation, Johnson & Johnson, The Procter & Gamble Company, and Ryder System navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation. Doug develops approaches, creates forums, and structures engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the ideas and to the collaboration that result.

As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL). Today, Doug works as senior practice leader at social innovation company Mindjet, where he consults with a range of clients. He focuses on helping them realize their potential for leadership by applying the practice of collaborative innovation.

Photo : Square blue icon guitar with long shadow by Shutterstoc.com