New Retail Displays, New Molecules

An organization’s culture is defined by the commitments people make to one another and by the practices they apply to keep those commitments.

People who pursue the practice of collaborative innovation intend to instill a culture of innovation within their organizations. The people they engage first contribute to that culture by offering and collaborating on ideas. The culture strengthens as the contributors enter the back end of innovation, where they explore the potential of their ideas through concepts, trials, analysis, and ultimately implementation.

Practitioners struggle less with the front end of innovation, once they have convinced stakeholders that pursuing the practice makes sense for the organization. The front end benefits from having a well-defined approach in both its virtual and in-person forms which practitioners can apply across many scenarios. The blueprint describes the approach.

By contrast, the practice that drives the back end of innovation varies by idea. First, we look at context. Does the idea relate to the core business? Does the idea relate to an emerging business? Does the idea represent a new venture? Second, we look at the learning curve. Exploring the possibilities of a new retail display requires certain skills. Exploring the possibilities of a new molecule requires others. Third, we look at resources. How many new ideas at each horizon can the organization pursue so as to renew the core business in the long term without crippling it in the near term?

The organization that became Lockheed Martin developed a successful approach for prosecuting back end innovation called the Skunk Works. In this article I revisit the Skunk Works model in the context of present-day approaches to collaborative innovation.

What can we learn by mixing the old with the new?

The Skunk Works

Lockheed Martin engineer Kelly Johnson developed and led what became the Skunk Works as a way to deliver a jet fighter for the Allied Forces during World War II in time to counter the Axis threat. The time constraint allowed him to pursue novel ways of working the back end of innovation which he later codified in 14 rules and practices. The rules are wonderfully direct and clear.

In this article I explore 3 of the 14 rules and practices, relating them to this column’s focus on collaborative innovation. I commend anyone looking for examples of successful back end innovation to read Ben Rich’s book, Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years of Lockheed, in order to appreciate what Johnson and he accomplished.

Designation of Authority

Skunk Works Rule: the Skunk Works manager must be delegated practically complete control of their program in all aspects. They should report to a division president or higher.

This rule speaks to common sense born of experience by anyone who has worked on the fuzzy front end of innovation. New concepts disrupt existing value streams, profit pools, and—by extension—compensation and hierarchy schemes. Incumbent businesses excel at quashing concepts that threaten the status quo. Governance matters.

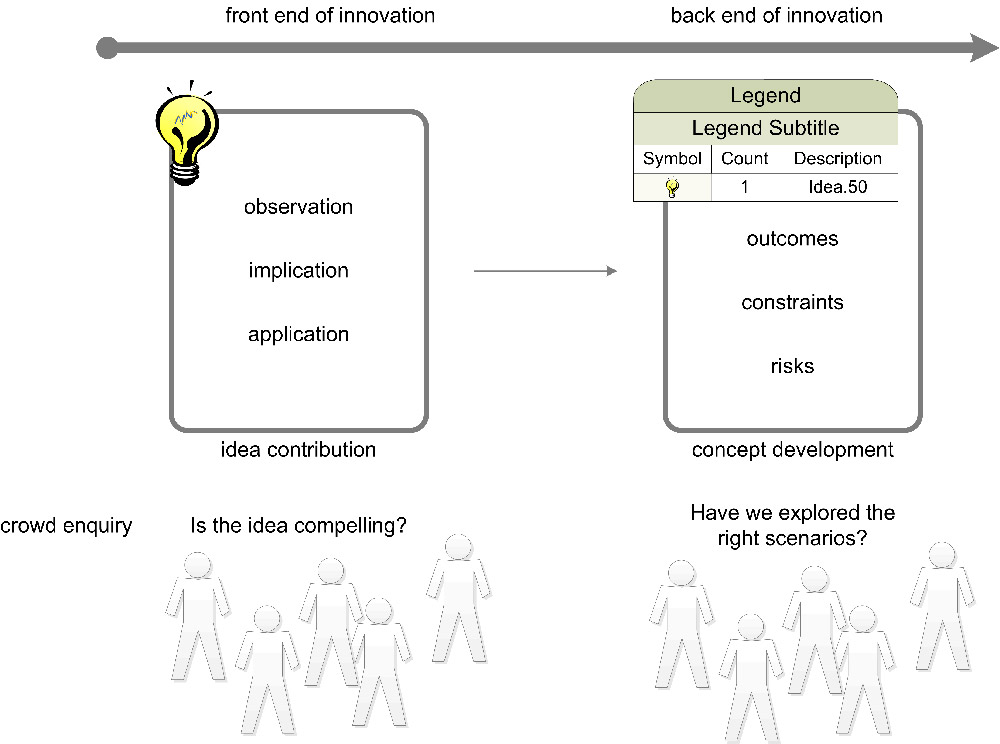

Relative to the practice of collaborative innovation as we have explored it here, the question becomes what relation does the challenge sponsor does the challenge sponsor and the idea contributor have with the equivalent of the Skunk Works manager (figure 1)?

Figure 1: the Skunk Works as back end incubator to a collaborative innovation feeder

I see two possibilities. First, if the organization has an established Skunk Works, then the hand off would be straightforward. The idea contributor moves from the sponsorship of the challenge sponsor to the sponsorship of the Skunk Works program manager, who already enjoys the designation of authority outlined in Kelly’s rule, assuming the sponsors are not one in the same person.

Alternatively, if the Skunk Works does not exist, then the challenge sponsor must either (a) designate the idea contributor as the Skunk Works program manager or (b) charter that role. They must create room to breathe.

This decision depends in part on where the challenge sponsor and the idea contributor stand in the organization. Per Kelly Johnson, is the challenge sponsor the equivalent of the division president or higher?

A Small Number of Good People

Skunk Works Rule: The number of people having any connection with the project must be restricted in an almost vicious manner. Use a small number of good people (10% to 25% compared to the so-called normal systems).

This rule, too, speaks to common sense. People who develop software will, for example, recognize in it Fred Brooks’ law: adding manpower to a late software project makes it later. The word vicious suggests to me the nature of the battles Kelly Johnson waged with the bureaucracy that defines the military industrial complex. The emphasis on good people resonates with people who have been given a charter and the wrong team to prosecute it.

What of collaborative innovation, in which challenge sponsors convene large groups of people to ideate?

Having a small group of talented people crafting and sculpting the concept continues to makes sense. At the same time, one could imagine today’s Skunk Works program team reaching out to the crowd to get their ideas on critical elements of the concept—outcomes, constraints, and context, for example—as they arise. Focused externally, the practice becomes a form of customer co-creation. The key would be to engage the crowd in limited, focused ways—to explore singular elements of the concept—without opening the tent for large-scale participation, which opens the door to bureaucracy.

Testing…

Skunk Works Rule: The contractor must be delegated the authority to test their final product in flight. They can and must test it in the initial stages. If they don’t, they rapidly lose their competency to design other vehicles.

I favor this rule above the rest. How many of us have witnessed the slow-motion disaster that is the untested concept brought to market too soon?

The application of collaborative innovation relative to this rule may simply be a commitment to brainstorm completion criteria, along with the risks that endanger a successful launch of the concept in question. Opening this part of the work to a larger group helps the small project team avoid neglecting the full range of scenarios to explore through testing (figure 2). James Surowiecki explores the risks of groupthink in homogenous, hierarchical crowds in The Wisdom of the Crowds.

Figure 2: engaging the crowd on the front and back ends

Parting Thoughts

People who lead the back end of innovation need creativity, courage, competency, and savvy: powerful leadership competencies. If you are not making the core business and the hierarchy in your organization nervous, then you likely are not prosecuting the back end effectively, as Kelly Johnson did for years at Lockheed Martin. The nature and phrasing of his rules indicate the war that must be waged in order to deliver meaningful innovation. His rules enjoy the benefits of being proven, being simple to grasp, and appealing to our common sense.

Fast forwarding to today, the practice of collaborative innovation may benefit Skunk Works programs by (a) feeding the program candidate ideas to pursue and people with leadership potential to pursue them, (b) giving the program team a means to engage the crowd without having the crowd become meddlesome bureaucracy, and (c) helping the program team vet outcomes and risk reduction strategies that they, small in number, may miss or choose to ignore during concept testing. The practice in this context becomes a useful tool for focused engagement.

By Doug Collins

About the author

Doug Collins is an Innovation Architect who has specialized in the fuzzy front end of innovation for over 15 years. He has served a variety of roles in helping organizations navigate the fuzzy front end by creating forums, venues, and approaches where the group can convene to explore the critical question. As an author, Doug explores the critical questions relating to innovation in his book Innovation Architecture, Practical Approaches to Theory, Collaboration and Implementation. The book offers a blueprint for collaborative innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management.

Doug Collins is an Innovation Architect who has specialized in the fuzzy front end of innovation for over 15 years. He has served a variety of roles in helping organizations navigate the fuzzy front end by creating forums, venues, and approaches where the group can convene to explore the critical question. As an author, Doug explores the critical questions relating to innovation in his book Innovation Architecture, Practical Approaches to Theory, Collaboration and Implementation. The book offers a blueprint for collaborative innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management.