A growing number of firms have realized that their innovation goals cannot be fully satisfied solely through their internal resources. Consequently, managers are increasingly supplementing their internal innovation efforts by tapping into the knowledge of external collaborators, taking an open innovation perspective (Chesbrough, 2003, Elmquist et al., 2009).

Other types of stakeholders, such as competitors, activists and special interest groups have become active, well-informed and interconnected partners for innovation.

Traditionally, these external collaborators consisted of one type of external stakeholder, often other firms or customers. Nowadays, the sources of innovation are changing. Other types of stakeholders, such as competitors, activists and special interest groups have become active, well-informed and interconnected partners for innovation.For example, last year we studied a project where a large global pharmaceutical & health care firm was looking for new ways of delivering medical supplies to remote areas in developing countries. In order to achieve this, our focal company collaborated with an NGO, a fast moving consumer goods company, local distributors of FMCG and local governments.

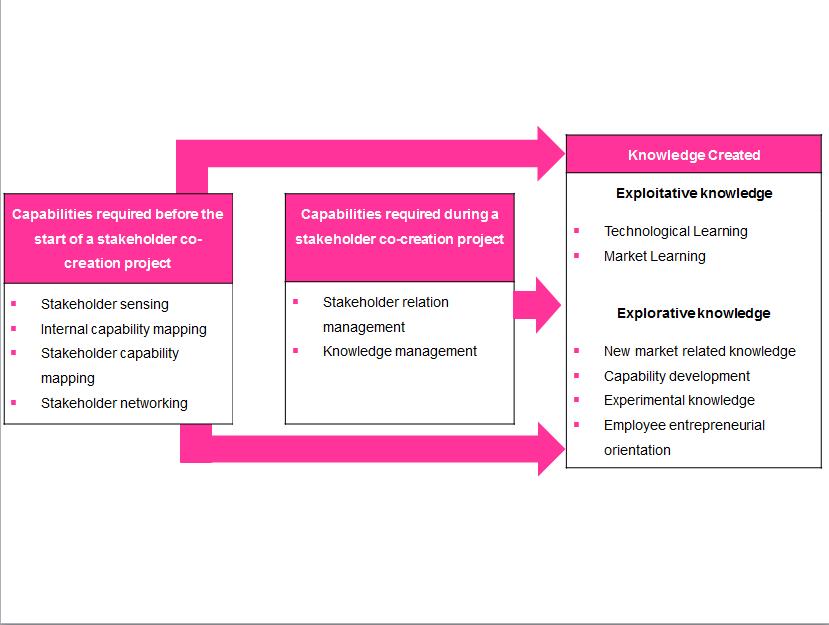

Capabilities required before the start of a stakeholder co-creation project

In order to make a stakeholder co-creation project a success, a leading firm needs to lay the groundwork before a project actually starts. In order to do so, it requires four specific capabilities:

- Stakeholder sensing,

- Internal capability mapping,

- Stakeholder capability mapping and

- Stakeholder networking capability.

A leading firm might send one or more of its employees for a three month job-exchange to a NGO

Stakeholder sensing denotes a firm’s ability to constantly monitor, register and disseminate information with regard to a multitude of its stakeholders. It goes beyond the traditional market sensing capability (Day, 1994) as it covers a wider range of actors and different types of information than those considered in traditional market sensing. Traditional market sensing limits the types of actors considered to customers, competitors and channel members. Other types of stakeholders (e.g. activists) are only considered when they exert an influence on customers. Investing in stakeholder sensing is constantly gathering information on a wide range of stakeholders, codifying this information and distributing this information across various departments. For example, a leading firm might send one or more of its employees for a three month job-exchange to a NGO.

Internal capability mapping refers to a firm’s ability to identify and catalog their internal capabilities. Having an overview of the capabilities present within a firm is an important prerequisite for engaging in stakeholder co-creation projects. Only when a firm has a good assessment of its internal capabilities, managers can look for and find complementarities with external stakeholders in terms of capabilities. This might be done through a database that describes the specific competences within each department.

Stakeholder capability mapping is a firm’s ability to map the capabilities of previously identified stakeholders of interest. Before a firm engages in a co-creation project with multiple stakeholders, it may benefit from having a clear picture of the capabilities each stakeholder possesses. For example, by organizing regular exploratory meetings with different types of stakeholders proposing new possible activities for the firm to engage in. Hereby keeping an eye on what these stakeholders’ current level of capabilities is in areas where the leading firm needed complementary capabilities.

As these stakeholders are not always organizations with a profit-maximizing goal, firms need to approach these stakeholders in different ways than they would in a traditional partnership between firms.

Stakeholder networking capability describes a firm’s ability to connect with a wide range of stakeholders that offer opportunities for engaging in a co-creation project. Yet, not each connection needs to necessarily be related to a specific co-creation project. Specific internal guidelines and routines enhance the ability of maintaining a relationship with a wide range of stakeholders creates more opportunities for future co-creation projects. For example, during our case studies we found that within large firms, it is difficult to communicate in one voice concerning their innovation goals. Thus setting up and communicating an innovation road map is crucial. Failing to do so results in certain stakeholders not trusting the leading firm and hence rejecting a collaborative relationship. Furthermore, as these stakeholders are not always organizations with a profit-maximizing goal, firms need to approach these stakeholders in different ways than they would in a traditional partnership between firms. Otherwise, these stakeholders would see no value in potential co-creation activities with the leading firm.

Capabilities required during a stakeholder co-creation project

We are well aware that successful innovation projects require a broad set of capabilities. A lot of which have been described by other authors on this website. Here, we describe two capabilities which we have found to be specifically important when dealing with projects that involve multiple external stakeholders simultaneously. These are

- Stakeholder relational capability and

- Knowledge management capability.

Stakeholder relational capability is a leading firm’s ability to manage its relationships with a multitude of stakeholders in an ongoing co-creation project as well as the relationship of those stakeholders amongst each other. Collaborations are more difficult to manage when interests, goals and practices of all actors involved differ. Different types of stakeholders involved in one innovation project have different goals.Therefore, a leading firm should be and act as a facilitator, trying to explicate each stakeholder’s goals and interests in order to find common ground. Activities that help voice each stakeholders’ goals and voice any problems in this complex partnership are crucial.

A symphony cannot be played without all members of the orchestra interacting.

Knowledge management capability is a firm’s ability to acquire, store and disseminate knowledge emanating from interaction with its different stakeholders, and also from the interaction of those stakeholders amongst each other. While this links closely to the concept of absorptive capacity, there are several key differences. First, most research on absorptive capacity focuses on acquiring knowledge from other actors up- or downstream in the value chain (i.e. suppliers and customers). However, knowledge also resides within other types of stakeholders, which require a different approach to maintain knowledge relationships than more traditional partners.

Even further, as knowledge is a result of the interaction between different parties (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995), certain types of knowledge may only be generated and maintained when several specific types of stakeholders are involved simultaneously. Metaphorically, a symphony cannot be played without all members of the orchestra interacting. Thus, when one of these stakeholders is no longer involved in the project, knowledge may disappear. Therefore, clearly mapping which stakeholder brings what complementary knowledge to the table is a key requisite for successful stakeholder co-creation.

Thus, these six capabilities allow the conductor (leading firm) to prepare itself for co-creation with a diverse orchestra of stakeholders and subsequently perform the actual co-creation project successfully. The following sections describe what the leading firm might learn from such stakeholder co-creation projects.

Exploitative and explorative knowledge created through stakeholder co-creation projects

Successful product innovation is contingent on balancing exploitation and exploration strategies (March, 1991). Exploitative knowledge enables a firm to profitably exploit its current resources. In other words, exploitative knowledge helps to improve the day–to-day activities of the leading firm. Explorative knowledge is what helps a firm to adjust its skills and resources in order to tackle changes in the environment in the long run. Our research indicates that a firm can harness both exploitative and explorative knowledge from stakeholder co-creation projects.

Exploitative knowledge created through stakeholder co-creation

With regard to exploitative knowledge creation, stakeholder co-creation projects can drive:

- Technological Learning and

- Market learning.

First, technological learning denotes all knowledge that helps a leading firm improve its current technologies. Our case studies have indicated that, by co-creating with multiple stakeholders, firms were able to acquire previously unattainable information in relation to technologies they were currently using. This newly generated technological knowledge is not only beneficial for the department active in the stakeholder co-creation project but also spills over to other departments within the leading firm.

Certain stakeholders are better informed about the needs and wishes of a firm’s target segment than the firm itself.

Second, firms, that engage in stakeholder co-creation have the benefit of gaining market information which might be costly or impossible to access otherwise. Certain stakeholders are better informed about the needs and wishes of a firm’s target segment than the firm itself. Hence, collaborating with these stakeholders offers a possibility to acquire this information.

Explorative knowledge created through stakeholder co-creation

Our research revealed four types of explorative knowledge created through stakeholder co-creation:

- New market related knowledge,

- Capability development,

- Experimental knowledge and

- Employee entrepreneurial orientation.

First, by bringing together stakeholders in a co-creation project, a leading firm can gain knowledge about- and even access to markets which were previously inaccessible. Our research results indicate that firms may gain knowledge, and eventually expand into new markets through the complementary capabilities of stakeholders.

Second, firms have the opportunity to build new capabilities out of knowledge gained from stakeholder co-creation projects. Single projects often pave the way for organizational change by introducing new capabilities (Leonard-Barton, 1992). Stakeholder co-creation projects may do just that, by generating knowledge that contributes to the buildup of new capabilities. Even in other areas within the firm. For example, a large multinational firm can learn a whole lot about marketing products in remote areas by co-creating products with an NGO.

Stakeholder co-creation projects help employees to ‘not play it safe’

Third, experimental knowledge is insight gained from small, targeted experiments. Stakeholder co-creation projects may offer an opportunity for firms to conduct such small experiments, which result in a portfolio of possibilities. This portfolio of options aids a firm in addressing fast changes in complex, high-velocity markets (Day, 2011). Stakeholder co-creation projects help employees to ‘not play it safe’ because the projects are outside of their normal comfort zone. So these kind of projects allow for failure because they may present various learnings.

Fourth, employee entrepreneurial orientation denotes the development of ‘entrepreneurial spirit’ in leading firm employees who participated in stakeholder co-creation projects. Throughout our studies it became apparent that engaging in these type of co-creation projects with stakeholders had a strong impact on the leading firm’s employees who were part of a project. Several managers indicated that they wanted to encourage employees to take initiative and explore new paths.

Thus, through managing a co-creation project with multiple stakeholders successfully, the conductor (leading firm) may simultaneously acquire different types of exploitative and explorative knowledge.

References

CHESBROUGH, H. 2003. Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology, Boston, MA, Harvard Business Press.

DAY, G. S. 1994. The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58, 37-52.

DAY, G. S. 2011. Closing the Marketing Capabilities Gap. Journal of Marketing, 75, 183-195.

ELMQUIST, M., FREDBERG, T. & OLLILA, S. 2009. Exploring the field of open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 12, 326-345.

LEONARD-BARTON, D. 1992. Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 111-125.

MARCH, J. G. 1991. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2, 71-87.

NONAKA, I. & TAKEUCHI, H. 1995. The knowledge-creating company, Oxford University Press.

About the Authors

Kande Kazadi is a doctoral candidate at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, working under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Annouk Lievens and Dr. Dominik Mahr (Maastricht University). His research focuses on the simultaneous involvement of multiple stakeholders in a firm’s innovation process. His current project has been selected as a winner of the Product Development & Management Association (PDMA) Research Competition.

Annouk Lievens is a Professor of Marketing at the University of Antwerp, Belgium and chairwoman of the Marketing Department. Her research centers on service innovation management, knowledge creation and organizational communication within services organizations. She has published in journals such as the International Journal of Service Industry Management, Journal of Product Innovation Management, European Journal of marketing, Journal of Service Research, Journal of Management Studies, The Journal of Business Research and Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science.

Dominik Mahr is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Marketing and Supply Chain Management of the School of Business and Economics, Maastricht University. His research interests are in open innovation, customer co-creation, digital media, knowledge creation, healthcare and strategic marketing. Dominik’s publications have appeared in journals like Journal of Product Innovation Management, BMJ Quality & Safety (previously Quality & Safety in Health Care), Health Policy and Research Policy.

Photo: BUDAPEST – JAN 13: MAV Symphonic Orchestra fron shutterstock.com