By: Doug Collins

Organizations shake and remake themselves to survive and thrive in the Digital Age. What critical conversations need to happen amongst stakeholders? What processes need to change? How might the practice of collaborative innovation help people find their way forward?

This past fall our columnist the innovation architect Doug Collins began to tell the tale of how the Dirty Maple Flooring Company came to embrace the Digital Age through the practice of collaborative innovation. The latest episode appears below. Readers may navigate the full series here.

Charlie Bangbang Plans His Engagement

Charlie sipped his coffee—his morning jolt, as he thought. He gazed through the tempered glass that served as the east wall of his office. The geese on the retention pond paddled away from the rising sun to the near shore. Charlie imagined they were close to achieving the quorum needed to decide their migration date.

Charlie favored the fall. The air, cool and lacking the summer’s humidity, sharpened his thinking and quickened his step. Thoughts of shoveling and scraping that inevitably followed could wait.

Janet Sims-Raygun, his assistant and confidante for the past six years, leaned on the oaken frame of his door.

“Time to break out the skis, Mr. Charlie?” she enquired.

“Not yet. Let’s not rush things.” Charlie weighed the pros and cons of convincing Kaylee Jo to join him on his cross country treks Saturday mornings, when the world stood still for him. He loved his time with her. Cross country, to be enjoyed, demanded a practiced grace aided by a muscle memory she did not yet enjoy. He weighed the tedium of her complaints—too hard, too hard—with the pleasure of her company.

Frankie stopped, too, at his door. Charlie brightened: his silent supporter.

“What’s the good word today, Charlie? I see your friends are about to leave you,” as she gazed out the window with him.

“Yes, indeed. Perhaps they can check the Campeche plant with Roger once they land.”

Frankie and Janet laughed. Certain executives at Dirty Maple were famous—infamous—for visiting the southern plants when the weather turned cold in Wisconsin. Between the two of them, Frankie and Charlie knew where most the bodies were buried at the company.

“Come have a look, Frankie—your name is on this, too,” Charlie said, pointing to his monitor. Frankie came. Charlie had a Microsoft Word document with Dirty Maple letterhead open. It read as follows (figure 1).

Figure 1: Charlie and Frankie convene the innovation team

The accountant in Frankie compelled her to read the note twice. “Hit ‘send’,” she concluded.

Charlie pressed the key.

“You did not give them a lot to work with,” she said, observing the note’s brevity.

“That’s right—that’s exactly right. Whatever we do, Frankie, in introducing the practice of collaborative innovation into the company, we have to take a light touch. Last year the general staff, including the country managers, revolted in reaction to the amount of data and presentations the planning process demanded. We cannot PowerPoint our way to clarity and shared understanding. I want us to cut the administrative overhead in half and then half again.”

An image of Kaylee Jo and him gliding on their Telemarks appeared to Charlie. He smiled.

“Whatever you say, Mr. Charlie,” Frankie affirmed. Charlie winced. He recalled that Frankie had a low threshold for lectures, no matter how authentic the delivery.

Dirty Maple Follows the Middle Class

Frankie extracted from her Coach Crosby portfolio a paper copy of a spreadsheet that, on a page, summarized Dirty Maple’s financial state for the quarter and year to date, by region. Nearby columns showed actuals versus projected, along with period-over-period comparisons.

The sheet conveyed to Charlie that, in a nutshell, Dirty Maple’s business strategy was to follow the middle class as it emerged around the globe. As regions, countries, and communities developed, gaining economic wealth and political freedom, the demand for hardwood flooring and cabinetry grew. The company was experiencing high growth in Southeast Asia, Brazil, and Mexico, in particular. Growth remained elusive in the U.S. and Europe, by comparison.

Harry Lundstrom the CEO liked to say, “first dirt floors, then schools, then concrete floors, then the vote, then us.”

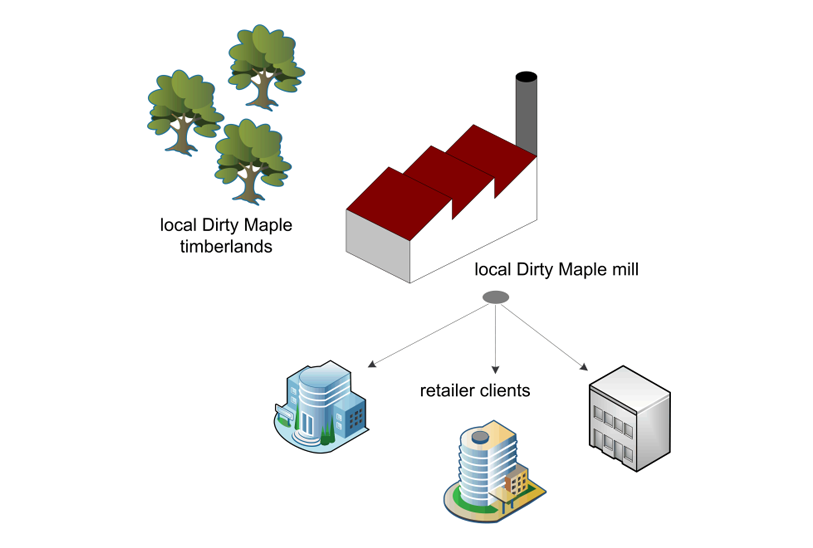

As a natural evolution of this strategy, Dirty Maple found itself with mills and warehouses in eight locations worldwide, including the first plant in Mt. Caca, north of the city. Each mill served an ecosystem of wholesalers and distributors which in turn served a couple hundred storefronts (figure 2).

Figure 2: Dirty Maple’s operations at the country level

Dirty Maple focused on the higher end of the market with fine-milled hardwoods so as to stay out of the crosshairs of local producers who often received favorable treatment by the municipal governments.

The company, with a history of promoting its own people, appointed experienced line managers such as Carlos, Ivete, and Benyamin, to serve as country managers. The country managers oversaw the supply chain and relations with retail clients. Dirty Maple—Frankie, in particular—relied on the country managers for demand forecasts which then guided all manner of decisions relating to financial leverage, turnover, and profitability. Carlos, Ivete, and Benyamin enjoyed varying degrees of success in pursuing their charter of providing accurate demand estimates. The gap between actual and projected for each of them, along with their peers, seemed to vary at random. High growth never meant consistent growth.

Frankie and Charlie Map the Critical Conversation

“I would value your perspective on how to frame our talk with Carlos, Ivete, and Benyamin this Thursday,” Charlie said to Frankie. “How might we avoid a speculative free for all?”

Charlie and Frankie approached Charlie’s white board which held an ever-evolving series of lines, circles, and stick people that defied ready interpretation, absent a guided tour by their illustrator.

“Have a look,” Charlie asked Frankie. She saw the following compass drawing competing for space in the middle of the board (figure 3).

Figure 3: framing the critical conversation

Frankie observed the critical factors that tended to arise when the headquarters staff and the country managers compared notes on demand forecasts.

“Looks about right to me,” Frankie said. “I am open to alternative suggestions by our colleagues, too.”

“Me, too, Frankie, me too. I find, however, that giving people a place to start with a simple visual on a page helps move things along. I was thinking about pointing my laptop camera at the white board for our call.”

“Maybe, Charlie. Nine times out of ten, I cannot make heads or tails of your scribbling. Best clean it up for our guests.”

“Fair enough, Frankie. Hey, switching gears, I owe you lunch at the Wellington. I think Casey put his pot roast special on the fall season menu today.”

“Sounds good, Charlie. Let’s go after this morning’s budget meeting.”

About the author

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He helps organizations such as The Estee Lauder Companies, Jarden Corporation, Johnson & Johnson, The Procter & Gamble Company, and Ryder System navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation.

Doug develops approaches, creates forums, and structures engagements whereby people can convene to explore the critical questions facing the enterprise. He helps people assign economic value to the ideas and to the collaboration that result.

As an author, Doug explores ways in which people can apply the practice of collaborative innovation in his series / Innovation Architecture: A New Blueprint for Engaging People through Collaborative Innovation. His bi-weekly column appears in the publication Innovation Management. Doug serves on the board of advisors for Frost & Sullivan’s Global community of Growth, Innovation and Leadership (GIL).

Today, Doug works as senior practice leader at social innovation company Mindjet, where he consults with a range of clients. He focuses on helping them realize their potential for leadership by applying the practice of collaborative innovation.

Photo: Canadian Goose swimming in a small pond from shutterstock.com