A organization’s ability to bring to best use the individual, team and collective creativity of its people is an important differentiator. That being widely acknowledged, organizations strive for diversity: diversity in gender, age, education, culture and so forth. The argument here is that they can’t overlook another type of diversity: that of being creative.

The under-appreciated obvious

There is nothing new about the call for creative diversity. In December 2007, Coyne, Clifford and Dye published an article in Harvard Business Review entitled “Breakthrough Thinking from Inside the Box.” They stated the obvious that nobody seemed to have noticed: People who like to explore “inside the box” should not be under-appreciated.

Seen in the light of cognitive science, solving problems and being creative is one and the same thing.

This point is backed up by robust research in cognitive psychology. Since the 1970s, Dr. Michael Kirton has been exploring how people solve problems. Seen in the light of cognitive science, solving problems and being creative is one and the same thing. As Genrikh Saulovich Altshuller, inventor himself of the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ), observed: Inventors are able to see problems where the rest of us have grown used to living with the hassle.

Acknowledging these key elements, Dr. Kirton investigated how people actually solve problems. Complex problems are solved in teams, which comes at a price. If you want to solve a technical “Problem A” with your team, then you have to face the additional “Problem B” of managing that same team: finding a place and time to meet, going through the stages of team development and tackling the team’s diversity.

In his research, Dr. Kirton found that people tend to confuse two things: level and style of creativity. If someone’s style of being creative is different from yours, then you might conclude that their level of creativity doesn’t match yours. Examples abound: For some time, Tesla worked for Edison. Both are recognized to have been highly creative people, but creative with very different styles (see this study for more). To solve difficult problems, we need creative diversity in our problem solving teams, but then we struggle to deal with it.

A continuous spectrum from adaptive to innovative styles of creativity

For his research on how people are creative, as opposed to how creative they are, Dr. Kirton developed a psychometric instrument called the KAI, which stands for Kirton Adaption-Innovation. The underlying inventory of questions helps practitioners evaluate the way people like to solve problems and how they are creative. The research behind that instrument makes it one of the most robust psychometric instruments I have come across.

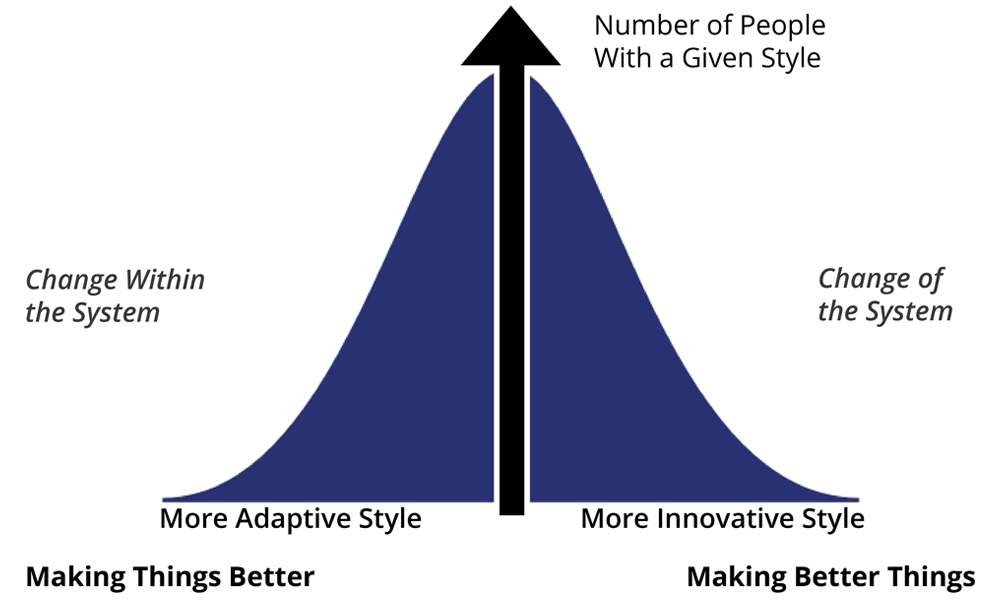

Figure 1: The continuous range of problem solving styles and the essence

of Dr. Michael Kirton’s Adaption-Innovation Theory.

Decades of research using the tool have allowed a number of insightful conclusions, including:

- On a continuous scale, people’s creative styles range from highly adaptive (like Edison) to highly innovative (like Tesla) while most people are somewhere in the middle.

- Over their lives and with experience, people change other personality traits but not their preference for how they solve problems.

- People can behave out of their own styles and “cope” with other styles—yet that causes stress; even minor differences in preferred style are measurable and lead to predictable patterns of individual and team behavior.

- There are three distinct yet correlated sub-categories of problem solving style:

- How well-thought-out our ideas need to be before we share them

- How much we like to exploit the details of a problem

- How much we care about the team and rules while solving problems.

Insights gained help individuals understand their own preferred problem solving style, appreciate their colleagues’ styles and manage diverse teams so that complex problems can be solved.

My organization has been applying the Kirton Adaption-Innovation Theory to help understand specific situations where team diversity and problem solving style are in play. Continuous improvement teams are frequently faced with challenges such as: Should we take a “deep dive” into the workings of a process or a machine in order to improve it or should we replace it with a new process or a new machine? Similar challenges are faced in R&D: Should we launch the next product generation with enhanced features or should we go for a completely new product? These are important business decisions—and their answers can be driven by the personal style of individuals rather than by the nature of the challenge.

Insights gained with the Kirton Adaption-Innovation Theory help individuals understand their own preferred problem solving style, appreciate their colleagues’ styles and manage diverse teams so that complex problems can be solved. We want to share a few specific case study examples.

Case Study #1

Lynda, HR professional, is promoted to lead a team in Finance

Talking to Lynda shows how organized she is. During school vacations she engaged in church and community work and later secured internships with companies. She then studied psychology and history, married early, had her first baby during a semester break and the second at the end of her studies. With the help of her parents and husband, she alternated between taking care of the kids and starting her professional career in the Human Resources department of a global organization. After some time in this role, Lynda took up an e-MBA. Upon its completion, she was promoted to head a team in Finance.

We met Lynda on her sixth month into the new job—exhausted. She remained a stranger to her team and had learnt to communicate with the rest of the team mostly through Luís who she felt was closest to her. Lynda didn’t think the problem resided in her not mastering the language of finance; with her MBA she often had more breadth and depth than most in her team.

“I am afraid they just think I am stupid,” she said. “And I must say I believe they are a bit irresponsible at times.”

“Why so?” we asked.

“Well, look at our new plant in China. The financial results for last quarter didn’t meet the bearish analyst expectations. And we don’t like to surprise markets. They decided to depreciate the plant a bit faster. That was a fast decision and they did not do the research. I haven’t even seen proper minutes of that meeting.”

“How do you think such a question should be handled?” we asked.

“In Finance it’s all about due diligence,” Lynda countered. “When we hire a candidate, we have a rigorous process to follow. And that makes sense. It’s ‘HR due diligence’ if you like. I am so frustrated by the very practice I see in my Finance team.”

“Did you talk to them about that?”

“More than I should,” Lynda sighed.

Over the next weeks, we had a chance to conduct a KAI analysis with Lynda and her team. The result is summarized in Figure 2.

If only I had known about that earlier. Then I could have approached our different views in a more conscious, diligent manner.

Lynda grasped the result immediately: “It is so obvious why Luís is doing all the translation work between me and the rest of the team. He is in fact bridging between my creative style and the styles of the others. If only I had known about that earlier, then I could have approached our different views in a more conscious, diligent manner.”

Case Study #2

Hassan, R&D manager from France, is promoted to lead a team in Germany

Hassan from Lebanon has studied in one of France’s prestigious Ecoles d’Ingénieurs. His ease of embracing complex problems by taking things apart and putting them back together in surprisingly effective ways has earned him a fast career in R&D. The company decided the next step would be a role in Germany, a country of which neither he nor his family spoke the language.

Once there, Hassan found there was more than one person who thought an outsider shouldn’t be heading the team. Hassan was eager to earn the team’s respect. The situation produced itself soon. Among the things Hassan reviewed with his team were the numerous reports they were supposed to send out on a daily, weekly and monthly basis. Hassan had all those reports meticulously listed on a whiteboard. Together with the team, he then assessed the ease of creating the reports and their perceived usefulness, as seen by the team itself. The results clearly showed how wasteful the team thought these reports were.

“You know what,” Hassan said, “we will simply discontinue three of the reports and see what happens. We are in R&D in the end and this will be an experiment we are going to run,” he said with a big smile.

“We’ll get a boatload of criticism,” someone remarked. “They think already we are not doing our work, and they believe with these reports they can control us better.”

Hassan insisted he wanted to stand for it: “Let’s still do that. And let’s also work on our internal reputation.”

Hassan’s gamble proved successful. For six months, nobody seemed to notice. The team set up and executed an “internal marketing plan” in parallel and later reviewed all the reports, which could then be boiled down to a handful of essential and short ones.

What is the secret behind Hassan’s success? Overall he is a more adaptive person. Yet, when you meet him you realize what you can also read from his KAI profile: His “team and rule conformity” is way more innovative than his overall style would predict. In other words, as an adaptor he is at ease with breaking the rules. He does it naturally, and in his case, you would marvel if your rules were broken in Hassan’s charming way.

Case Study #3

Klaus, an experienced consultant, survives only a few days at a client

One might conclude that a style like Hassan’s is better than others. In fact, any given style can be great in some situations and dangerous in others. Let’s look at Klaus, who like Hassan is more an adaptor and at ease with breaking rules or not going along with the team in order to solve problems. Having a team member with such a style can save your team from “group think.” In an adaptive environment, though, a style like Klaus’s can be misunderstood as cavalier towards the team. An overall more innovative person might get away with breaking the rules, but for someone who is otherwise a strong adaptor, such behavior can come as a surprise and be interpreted not as “style” but rather as “disrespect.”

Klaus started work for a global organization that has hundreds of similar service stations across the globe. They are proud of a continuous improvement practice that is able to copy even a minor improvement in one site into their global network and thus generate millions of savings out of, say, removing the need for an additional printer. One can conclude that adaptive, incremental problem solving is a key strength of the organization.

The drama unfolded in a predictable way. Klaus facilitated a workshop to help identify “breakthrough opportunities.” His ice-breakers and the challenging questions he asked failed to gain appreciation from the team. Within a few days, Klaus, a skilled professional, had to leave that organization.

Know thyself: Understand your problem solving style

There are many other cases we could talk about. Take Nicolai, a high innovator who worked during his civil service with a social project in Brazil. His local counterpart was Joyce, a high adaptor. Both are very good at what they do. Yet, they are like fire and ice in the way they like to solve problems. Back in Germany we conducted a KAI analysis and talked about the situation. In the words of Nicolai: “If only I had known before! That would have helped me not to take her for stupid.”

To us, it all comes back to the wisdom first promoted by the Oracle in Delphi, Greece: “Know Thyself.” In order to work effectively together with people who have a problem solving style different from our own, we need to understand our own style of solving problems. That enables “seeing” other people’s styles relative to ours, which is the pre-condition for truly appreciating those differences.

Truly appreciating our differences in style is certainly the hardest to do. It is not true appreciation if you delegate to the adaptors on the basis that “they like the details anyway.” It is also not true appreciation if a more adaptive team finds innumerable ways to keep their innovative CEO out of their meeting so that “he doesn’t disrupt the consensus in the room.”

As you can see, there are myriad styles of how people solve problems and are creative. Developing the ability to make the best use of those styles is in fact a life-long journey. As individuals and as teams and organizations, we must continuously learn and grow that ability in order to solve complex problems together.

About the author

Dr. Michael Ohler is principal and manager of European operations for strategy and innovation consulting firm BMGI. He also leads the company’s innovation practice for European operations. With more than 20 years of experience, Michael focuses on using people-driven approaches to shape and execute transformations, coach senior leaders, and train practitioners. He is a frequent speaker and author on topics related to strategy and innovation.

Dr. Michael Ohler is principal and manager of European operations for strategy and innovation consulting firm BMGI. He also leads the company’s innovation practice for European operations. With more than 20 years of experience, Michael focuses on using people-driven approaches to shape and execute transformations, coach senior leaders, and train practitioners. He is a frequent speaker and author on topics related to strategy and innovation.

Photo : Bright colorful cube from Shutterstock.com