By: Paul Sloane

The aim of the precautionary principle seems laudable: lacking scientific consensus, the burden of proof for an action or policy not being harmful to the public or to the environment lies on those taking that action. In practice, however, this principle has proven a deterrent for innovation – particularly within the EU. How can the innovation principle – that is, examining new policies or plans for a negative impact they have on innovation – help to supplement and balance out the precautionary principle?

The precautionary principle states that if an action or policy has a suspected risk of causing harm to the public, or to the environment, in the absence of scientific consensus that the action or policy is not harmful, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those taking the action. The application of the precautionary principle has been made a statutory requirement in some areas of EU law.

Its aims seem laudable. The principle implies that there is a social responsibility to protect the public from exposure to harm, when scientific investigation has found a plausible risk. These protections can be relaxed only if further scientific findings emerge that provide sound evidence that no harm will result.

The intentions of the principle are good – to prevent another thalidomide tragedy. But as Matt Ridley, author of The Rational Optimist, argues in The Times; ‘At its worst the principle does huge harm because it says banish potential hazards without considering the benefits of an innovation while ignoring the hazards or an existing technology. Don’t do anything new.’

For example, EU rules on vaping restrict the marketing and functionality of e-cigarettes, making it much harder for this new technology to replace smoking. There may be some risks with vaping and the precautionary principle ensures that those risks override and preclude the benefits.

Europe is way behind Asia and the USA in developing genetically modified crops because certification in Europe is almost impossibly difficult. The result is that European farmers have to use less productive varieties of plants and more harmful pesticides. Meanwhile gene editing, which is being developed in US laboratories, has been put on hold in European ones.

In the 1950s, famine and hunger were common across large parts of the world. Two scientists, Borlaug and Swaminathan, developed IR8, a new semi-dwarf rice plant, with a much greater yield. It went on to save millions of lives. Fortunately for the people saved, the precautionary principle was not applied.

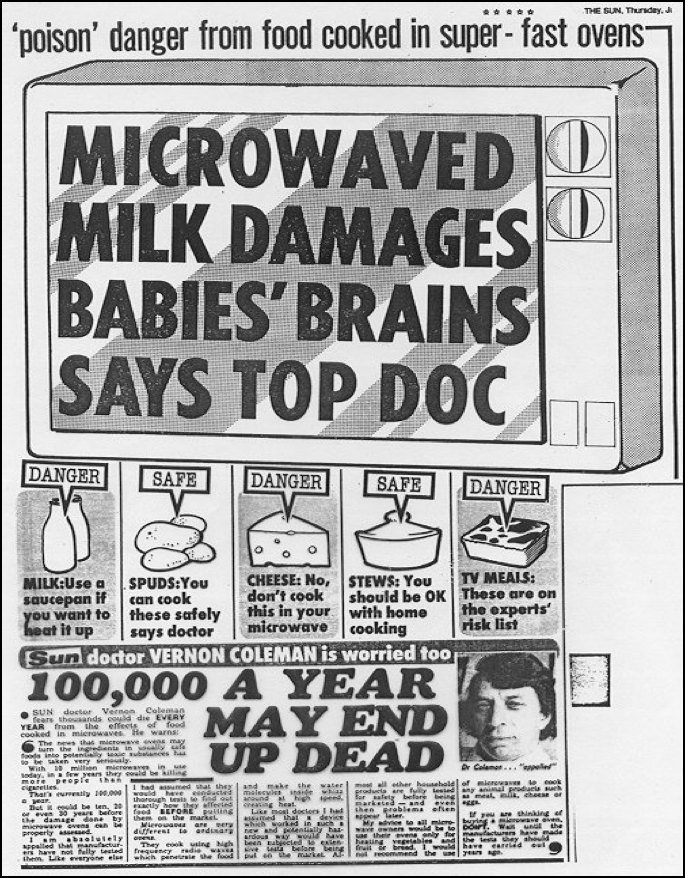

The precautionary principle has powerful, well-funded backing in the shape of the green lobby. They are supported by the media who love scare stories about ‘Frankenfoods.’ A good news story about the benefits of new crop types generates much less excitement and coverage.

The Sun Newspaper, January 1990

The trouble with the precautionary principle is that it deters innovation. It encourages an attitude of – if in doubt do not innovate. George Freeman, former UK life sciences minister, described the EU approach as “increasingly science hostile.”

We are now seeing increasing signs of a pushback. The European Risk Forum and the European Round Table of Industrialists are promoting a policy called the innovation principle. In brief it states – Examine every new policy or plan for the impact it could have on innovation. If the plan impedes innovation then rethink the plan. In 2014 some 22 CEOs of major organisations wrote an open letter to Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, asking him to endorse the innovation principle.

The innovation principle is not meant to replace the precautionary principle but to supplement it. Nobody wants to launch risky and untested products on the mass market. But a balance has to be struck and many think that right now the political balance is too cautious and risk averse. We need to adopt and apply a more innovative approach. We need to manage risk rather than always trying to avoid it.

Brexit will give the UK the opportunity to roll back EU regulation, to adjust the balance away from precaution and more towards managed experimentation and innovation.

About the author

Paul Sloane is the author of The Leader’s Guide to Lateral Thinking Skills and The Innovative Leader. He writes, talks and runs workshops on lateral thinking, creativity and the leadership of innovation. Find more information at destination-innovation.com.

Paul Sloane is the author of The Leader’s Guide to Lateral Thinking Skills and The Innovative Leader. He writes, talks and runs workshops on lateral thinking, creativity and the leadership of innovation. Find more information at destination-innovation.com.

Featured image via Yayimages.