By: Constance Casper / Volker Bilgram

While the previous two methods – Netnography and Social Media Solution Scouting – outline the potential of passive methods in using the power of social media for innovation, the next two approaches enable companies to interact with consumers. Configuration Tools as well as Innovation Contests invite users outside the company’s four walls to become an active part of new product development. In part two of this article you will learn how Audi and Henkel empowered the crowd and turned them into co-producers.

Go to part one of this article »

Method 3: Configuration Tools

Invite users to configure their ideal products

As opposed to the passive qualitative research approach of the Netnography, configuration tools are a predominantly quantitative approach. In contrast to the ‘natural’ environment of online communities (i.e. the virtual worlds users spend their spare time), companies set-up a research environment to interact with users. Configuration tools help companies to explore and determine those product variables which are preferred by consumers. This can be helpful at two different stages in new product development: In the very early phase, configuration tools help to point companies in the right directions for ideation and concept development. In this phase, the solution space within which users can make their choices is rather open and may even allow for users’ own suggestions. At a later stage, when initial concepts have already been developed, configuration toolkits provide a less open solution space for consumers to identify preferred variables, variable combinations and features of the concepts.

The power of play in marketing research

Configuration tools are rich in terms of visual support and playful interaction elements. These characteristics make them a very appealing and compelling research approach which users may not even consider research any longer. “Gamification” and “Serious Gaming” are terms describing this type of research that comes in the guise of play. Configuration tools rely on four core principles which support a play-like environment. First, the task at hand is to be embedded in a compelling narrative such as a storyline. Second, games need simple and clearly communicated goals and rules as the absence of rules may result in frustration and resentment among users. Third, ‘gamified’ co-creative processes need to provide fast feedback to spur users’ play instinct. And fourth, the game needs to set a suitable challenge with a well-balanced level of difficulty. Integrating these mechanisms is not only a way to collect valid data, but also a way to differentiate your research tools and make them more attractive to users. This is especially useful in a world in which conventional questionnaires are facing difficulties attracting consumers to provide them with valuable feedback.

Case 3: Audi Virtual Lab

An infotainment system developed with consumers

In two consecutive projects, more than 7,000 consumers from Germany, the USA and Japan participated in the Audi Virtual Lab, a web-enabled co-creation initiative revolving around Audi’s infotainment system for Audi’s A3 and A4 models. The aim of the project was to actively involve users even in the early phases of the technology-driven innovation process. The innovation team at Audi intended to gain information on consumers’ preferences regarding features of the infotainment system in order to reduce uncertainty. Car enthusiasts on Audi’s website and selected communities were invited to support Audi’s R&D by configuring their ideal infotainment system.The only users addressed were those highly involved and experienced in the field of car infotainment systems to ensure they were capable of assessing the innovative alternatives within the solution space.

Configure your ideal infotainment system

At the heart of the web-based platform was a toolkit enabling users to configure their ideal infotainment solution by choosing from existing components as well as virtual, photo-realistic components that were currently being developed (see figure 3). Infotainment systems in automobiles comprise a variety of components such as radio, navigation, telephone, sound system, control interfaces and location-based services. The complexity of Audi’s infotainment components was transformed into a compelling and easy-to-use virtual configuration toolkit. Users were required to make trade-offs due to personal budget restrictions or technical restrictions. These helped Audi’s R&D to identify “must-have” and “nice-to-have” features. In addition, the instant price information for selected features engaged consumers in an experience similar to a buying decision and prompted them to uncover their true preferences.

Making marketing research a compelling experience

Unlike many other traditional market research approaches, the Audi Virtual Lab managed to prompt consumers to immerse themselves in the activity. Users spent up to 40 minutes on the co-creation platform and also indicated their willingness to participate in future projects. The resulting preference data was structured according to Audi’s target groups based on demographic information. With the help of a “closest match” functionality, users’ preferred design variables could be aligned with Audi’s internal innovation roadmap. The user configurations were compared to pre-configured infotainment systems in order to test the acceptance of a cheaper compromising solution. In addition to the data on users’ preferences, Audi benefited from a huge number of service ideas which users were invited to submit on the platform. The setting of the virtual user toolkit appeared to be conducive to the generation of relevant ideas revolving around the new infotainment system. To date, the Audi MMI sets industry standards as a consumer-centric system and is continued throughout the Audi model range.

Figure 3: Configuration tool within the Audi Virtual Lab

Method 4: Innovation Contests

Connecting creative minds via crowdsourcing

Innovation contests utilize the knowledge and creativity of users to answer innovation tasks “broadcasted” by an organization, often on a temporary online platform. They make use of four major principles. First, the crowdsourcing principle is applied to outsource a task or question to a large number of users in the periphery of the company. Second, innovation contests are organized as competitions which offer a reward to a few winners who ‘take it all’. Third, innovation contests are community-based innovation tools which utilize community mechanisms, social ties and a sense of community to provide an enjoyable collaborative experience. Fourth, the recruiting strategy takes advantage of the self-selection bias in order to address users with the most creative potential. The recruiting process is a huge success driver. In order to determine the relevant fields for recruiting, user communities are identified via netnographic research.

Ideas for free

Users have often already developed solutions and are willing to freely reveal them. A main reason behind this openness lies in the fact that they have no imminent commercial interest but rather like the idea of helping a company with their ideas or gaining recognition from their peers as well as from the company. However, even when users do not have ready-made solutions yet, they can often build on profound knowledge. Users have extensive product know-how and use experience as they spend a lot of time pursuing their hobby. Hence, they constantly undergo trial and error processes to create solutions that better match their needs and refine them over and over again.

Case 4: Henkel Adhesive Packaging Design Contest

Next-generation adhesive packaging

FMCG company Henkel crowdsourced the task of creating innovative ideas and designs for consumer adhesive products to a crowd of users outside the company. In order to give users some guidance as to the exact needs and requirements of Henkel, three idea categories were suggested on the contest platform. The contest specifically asked for ideas in the fields of adhesive dosage and application, two-component adhesives and mixing as well as easy and convenient opening and closing of adhesive packaging. The ideas could be submitted within six weeks of the contest phase. 5,000€ prize was offered to the best three designs selected by a jury on the basis of the following criteria: sustainability, innovativeness, convenience, performance and aesthetic appeal.

Innovation ideas and brand relationship

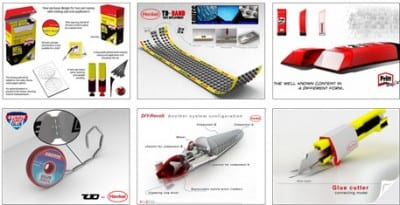

According to the goal of achieving not only rough ideas but also detailed concepts with a higher degree of maturity, the recruitment process aimed not only at consumers but also design students and hobby designers. In total, more than 1,000 users registered on the platform and submitted 385 ideas. Numerous user-generated ideas and designs were of outstanding quality and contained technical details as well as design aspects (see figure 4). Besides the competition for the best ideas in adhesive packaging, users exchanged thousands of comments and messages – a real temporary user community emerged. In addition to its primary goal of collecting fresh ideas, the contest also had significant effects on the user-brand relationship and the image of the company. The best ideas submitted by users were integrated into Henkel’s internal innovation process to be further elaborated.

Figure 4: Examples of ideas submitted by users during the contest

Challenges to Online Co-Creation

The systematic integration of users in new product development, however, also bears significant risks. This is particularly true for co-creation tools actively involving the user’s voice. Despite the emancipation of users from their role of buyers towards producing and consuming individuals (‘prosumers’), the original role allocation is still manifest. Consequently, barriers in the mindset of companies and users need to be overcome. Innovation managers need to be aware of the additional resources of innovation outside the company and gradually learn how to smoothly integrate co-creation tools in internal processes. On the other hand, for obvious reasons, users are very sensitive and skeptical about companies’ attempts to capitalize on their experiences, knowledge and creativity. Companies need to keep in mind that by approaching users they intrude into their world of enthusiasm and love for a hobby or activity with their rather profane commercial motives. Hence, a key task of co-creation enablers and intermediaries is to create a common understanding of the co-creation mode between companies and users. In co-creation approaches, users and companies need to meet at eye level and become coequal partners in new product development. Especially from the users’ perspective, feelings of being exploited for commercial purposes need to be avoided. Transparent communication, fair procedures and a just allocation of rewards are important drivers of successful co-creation initiatives.

The Right Co-Creation Mix

The four methodological approaches provide insights into how companies across different industries capitalize on the creative potential of users. Similar to the marketing domain, the formula for success in co-creation is all about the right mix of tools. In the first step, companies need to be aware of the outcome they wish to gain from co-creation, i.e. whether they are looking for need or solution information to propel their innovation efforts. Then, they have to decide between active and passive co-creation tools. This decision is mainly based on the specificity of the task (i.e. open or closed questions) and the degree to which they can open up towards outsiders.

While the examples visualize how each single method supports the innovation process with valuable information, it is noticeable that companies start to increasingly use multi-method approaches. Throughout consecutive steps in the innovation process they combine passive and active user integration in order to gain both need and solution information. For example, the sequential combination of the Netnography method and innovation contests has proved to be a fruitful approach. At the outset of the innovation process, Netnography helps to gain in-depth and unbiased insights that help to open up promising fields of innovation and learn about consumers. Subsequently, companies may apply ideation methods that actively integrate consumers. In innovation contests, users are invited to submit their ideas and solutions within the innovation fields derived from netnographic research. Hence, passive and active as well as need- and solution-driven co-creation methods yield the best results when they take turns and intertwine in the innovation process.

Today, co-creation comprises a plethora of different tools and methods which offer opportunities to perform different tasks throughout the innovation process. The challenge companies are confronted with is to select the right tools at the right time depending on the specific parameters of the innovation task. The cases provide insights into popular co-creation tools and into how companies apply these to spur innovation. Although co-creation is still in its infancy, it has apparently made its way into corporate innovation management in Germany. Even companies with a strong history of internal innovation are beginning to realize the potential of user innovation using co-creation tools.

By Volker Bilgram & Constance Casper

About the authors

Volker Bilgram is Associated Researcher at the TIM Group of the RWTH Aachen University and Team Lead Innovation Research at HYVE, a Co-Creation and Open Innovation enabler based in Munich. He graduated in International Business Law at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg with a focus on New Product Development and Open Innovation. He is currently doing research on the use of Co-Creation as an empowerment and branding tool for companies.

Volker Bilgram is Associated Researcher at the TIM Group of the RWTH Aachen University and Team Lead Innovation Research at HYVE, a Co-Creation and Open Innovation enabler based in Munich. He graduated in International Business Law at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg with a focus on New Product Development and Open Innovation. He is currently doing research on the use of Co-Creation as an empowerment and branding tool for companies.

Constance Casper is Senior Project Manager at the HYVE Innovation Research GmbH. Her focus lies on Netnography and how this method can be used to gain deeper consumer understanding to facilitate innovation processes. She graduated in Consumer Science at the TU Munich with a specialization in open innovation and lead user research.

Constance Casper is Senior Project Manager at the HYVE Innovation Research GmbH. Her focus lies on Netnography and how this method can be used to gain deeper consumer understanding to facilitate innovation processes. She graduated in Consumer Science at the TU Munich with a specialization in open innovation and lead user research.

Additional Resources

Beer, A., Casper, C., Katzer, R., Önal, Y. (2012): Listening to the voice of the people, Elements38, 1/2012, 34-41.

Bilgram, V., Bartl, M., Biel, S. (2011): Getting closer to the consumer: How Nivea co-creates new products, Marketing Review St. Gallen, 1, 34-40.

Chesbrough, H. (2003): Open Innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology, Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation, Boston.

Füller, J. (2010): Refining virtual co-creation from a consumer perspective, California Management Review, 52(2), 98-122.

Füller, J., Bartl, M., Ernst, H., Mühlbacher, H. (2006): Community based innovation: How to integrate members of virtual communities into new product development, Electronic Commerce Research, 6(2), 57-73.

Jawecki, G., Bilgram, V., Wiegandt, P. (2010): The BMW Group Co-Creation Lab: Managing an innovation hub for a panopticon of users, ESOMAR Innovate 2010 Conference Proceedings.

Kozinets, R.V. (1997): “I want to believe”: A netnography of the X-philes’ subculture of consumption, Advances in Consumer Research, 24, 470-475.

Morgan, J., Wang, R. (2010): Tournaments for ideas, California Management Review, 52(2), 77-97.

Nambisan, S., Nambisan, P. (2008): How to profit from a better ‘Virtual Customer Environment’, MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(3), 53-61.

Prahalad, C.,Ramaswamy, V. (2000): Co-opting customer competence, Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 79-91.

Sawhney, M., Verona, G., Prandelli, E. (2005): Collaborating to create: The Internet as a platform for customer engagement in product innovation, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(4), 4-17.

von Hippel, E., DeJong, J.P.J., Flowers, S. (2010): Comparing Business and Household Sector Innovation in Consumer Products: Findings from a Representative Study in the UK, Working paper.