By: Paul Sloane

In his book, “Messy,” economist Tim Harford argues cogently that we are wrong to strive for order and tidiness because openness, adaptability and creativity are inherently messy. We should appreciate the benefits of untidiness.

This provocative work contains many intriguing stories supported with references to academic research. Some of the insights and examples include:

- The distinguished jazz pianist Keith Jarrett was asked to play a concert on a piano that he found to be substandard. It was too quiet and the notes in the high registers did not play well. At first, he refused but then relented and produced an outstanding and original piece of work. Being restricted to substandard equipment forced him to improvise in clever ways.

- Phillips, Liljenquist and Neale ran an experiment where they compared the problem-solving abilities of teams. Some groups comprised four friends. Other groups comprised three friends and one stranger. The groups containing the strangers did much better. Interestingly, when the groups self-assessed, the groups of friends wrongly thought that they had done well and the groups with the stranger wrongly thought that they had done less well. We become complacent in homogenous groups – outsiders help to challenge our thinking. Team harmony is overrated.

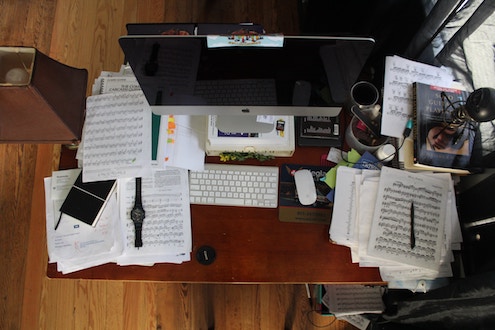

- Many organisations have rules about tidy offices. Clean desks look tidy but there is no evidence that they are helpful. On the contrary, all the available research shows that employees are more engaged in an office environment in which they are empowered to design and arrange. This nearly always means more messiness.

- When O2 had a major power outage their customers were greatly inconvenienced, and many went onto Twitter to air their grievances. Instead of responding with an anodyne corporate apology O2 allowed their support staff to improvise with humorous apologies. Someone tweeted “A carrier pigeon would offer a better service than O2.” The reply from O2 was “How much for the bird?” When one customer threatened to perform an unspeakable act on the support staffer’s mother the latter replied, “Mother says no thanks.” Allowing your staff to improvise rather than follow a script is not without risk but in this case, it worked well for O2 and garnered much good will.

- The German General Erwin Rommel relished chaotic situations because he believed he could think and react faster than his enemy. While his opponents were carefully preparing their next plan, Rommel would launch an unexpected attack – often from an unpromising position. He believed that the more uncertainty and chaos he could cause the better. Harford goes on to compare Geoff Bezos’s early actions with Amazon and Donald Trump’s surprise tactics in the Republican primaries with Rommel’s unconventional and messy approach.

- Harford argues that a standard battery of tests such as those that Volkswagen faced over vehicle emissions or the banks undergo for stress testing are too predictable. They can be gamed. It would be better if there were random checks under different circumstances and times.

- The paradox of automation is that the more automation we use the worse our skills become and the worse we are at dealing with situations when the automation fails. The classic example is the Air France 447 that fell out of the skies when the pilots had to take over from the autopilot and try to fly the plane. They failed. Tidy automation prevents us from developing the skills we will need when things turn messy.

- If there are too many warnings (about anything) then people tend to ignore them. If there are too many road signs, then people stop looking at them. Dutch experiments with city design show, counterintuitively, that messy junctions without traffic light controls and lots of signs force drivers to think and the result is good traffic flow and fewer accidents.

- Diverse cities and diverse economies do better and are more resilient than those that specialise in one or two sectors only.

- Children learn more from informal games where they have to improvise and make up their own rules than from standard games where the rules are clear.

Harford’s thesis is summed up in this quote from the book, “We have seen again and again that real creativity, excitement and humanity lie in the messy parts of life, not the tidy ones.”

By Paul Sloane

About the author

Paul Sloane is the author of The Leader’s Guide to Lateral Thinking Skills and The Innovative Leader. He writes, talks and runs workshops on lateral thinking, creativity and the leadership of innovation. Find more information at destination-innovation.com.

Paul Sloane is the author of The Leader’s Guide to Lateral Thinking Skills and The Innovative Leader. He writes, talks and runs workshops on lateral thinking, creativity and the leadership of innovation. Find more information at destination-innovation.com.

Featured image via Unsplash.