Platforms represent fundamentally different types of business. The future is really about platform transformation not innovation. Yet many companies are encouraged to focus on smaller tasks—the idea—instead.

As Roberto Verganti recently pointed out in The Harvard Business Review, problems arise when there are too many ideas around. “Thanks to powerful ideation approaches such as design thinking and crowdsourcing, it has become incredibly easy and relatively inexpensive for companies to obtain a vast number of novel concepts, from both insiders and outsiders such as customers, designers, and scientists. Yet many organizations still struggle to identify and capture big opportunities.”

In the case of innovation culture, there are many varieties of it. It is more difficult to know what are the essential elements of a culture of transformation. There are few guidelines for transformation strategy.

Perhaps Blue Ocean strategy? Seeking out uncontested space. That’s certainly a valid direction for platform ideation.

The development of new ideas along the tracks of two technologies or industries converging, as pointed out by Steven Johnson, gives another useful clue. Many of the major platforms, like Android and Apple’s App Store, emerged from the convergence of mobile telephony and computing.

Reconceptualising economic conditions also has value. As pointed out by people like Kevin Kelly and Peter Diamandis, in a digital world everything is abundant rather than scarce. We can scale businesses in ways never thought possible in the past.

The new game in town is the development of process model innovation skills

Already the platform economy is worth over $2.6 trillion.

Platforms are new process models. They are new ways of getting things done, new ways of organizing. Examples include: Uber, App Stores, the move to modularization of products, marketplaces for a wide variety of services, emerging industrial data platforms (GE), new participatory platforms, global clearing house platforms (IngDan for IoT technology).

This type of development is restructuring the global economy. Already the platform economy is worth over $2.6 trillion.

Over the past four years I’ve been looking at ways companies can bring significant change into being.

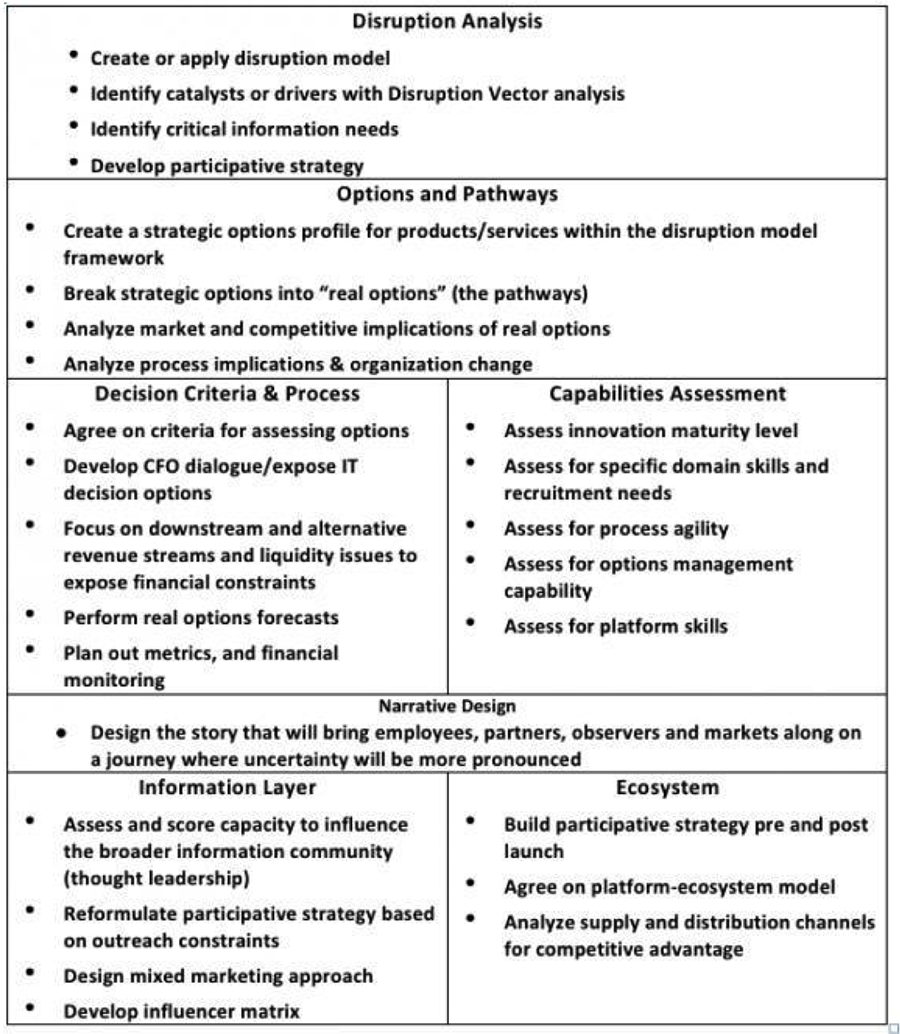

In the (new) tradition of getting to the point quickly, I have distilled my learning into a 7-step plan. The essence of the plan is to analyze disruption properly, to gain a full understanding of disruption scenarios and to move from this to platform strategies that are loaded with options.

Platforms provide flexibility

That idea of optionality is extremely important. Platform companies typically have many options available to them and they are not fail fast fail cheap options. They are strategic. For example, will Uber switch over to deliveries or will it go autonomous? These are major avenues of development and they are typical of the strategic flexibility that platforms enjoy.

Traditionally firms tried to suppress optionality – remember the strictures against adjacencies? Nowadays adjacencies are a vital component of strategy. That means executives need to think more in terms of the options they can generate and the decision processes that allow them to keep options alive.

In the development of strategically challenging processes, it is important to be mindful of the stresses on people who are being asked to think very differently. We know that “changing your mind” actually carries with it substantial psychic pain. But more of that in a separate article.

What follows is a summary of a longer paper. In part 1 of this series I will touch only on Step 1, continuing on to the next steps in upcoming articles.

The 7 Steps to Platform Disruption

Step 1. Disruption analysis

In earlier work I claimed there are four areas of disruption that will affect all companies, apart from more commonly understood factors such as technology or demography.

Adjacency platforms and convergence

Business platforms that combine a strong transaction engine, some form of productive ecosystem, and software differentiation originate in areas like hospitality (AirbNb), rides (Uber), smartphones (iOS, Android Xiaomi), etc. What’s new is that these platforms are moving to adjacent, seemingly unrelated market sectors areas – think iOS in payments, and Uber in delivery – where they offer value at low cost.

Traditionally innovation took place within an industry. Now it takes place across industry barriers.

In effect they are horizontal innovators. Traditionally innovation took place within an industry. Now it takes place across industry barriers. In fact, those barriers are falling.

Critically, platforms often emerge where there is a convergence of one industry with another as this gives an enterprising company the chance to reorganise the newly forming sector. It is vitally important to identify the lines of convergence.

Disruption factors:

- The availability of organizing platforms and large transaction-management engines

- The maturity of the entrepreneurial community in some sectors

- Large and growing ecosystems of startups and small companies seeking opportunity and prepared to compete with low pricing

- The ability to develop, organize, and liberate horizontal innovation across different industries

- Leadership that can bet on uncertainty, allowing the company to traverse new sectors without fear of failure

Creative destruction and experimental capitalism

The Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter wrote about creative destruction as an ideological reaction by entrepreneurs against oligopoly. Keeping in mind that Schumpeter’s reference point was the great cartel era of the early twentieth century, when modern antitrust laws were first created, the idea of entrepreneurs as rebels fits perfectly.

Steven Klepper adds to this line of thinking by showing that many companies that helped establish the tech industry in Silicon Valley were spun out of Fairchild Semiconductor. Klepper believed non-compete clauses stifle disruptive innovation and outlawing non-competes gives rise to dynamic clusters like Silicon Valley.

Renewal is commonplace. It happens periodically. Which is not to say it is always the same. Specific conditions apply to each era of change. The majority of western companies face constraints on their growth potential, yet are forced by financial markets to show predictable progress. And core technologies like open source and cloud computing reduce the cost of innovation, inviting a wave of disruptors into their markets and squeezing margins. Every company is susceptible to disruption.

By and large most industries that undergo transformation do so over a long period of time, Disruption takes at least 15 years. Before there was Cloud we experimented with client-server technologies. 20 years before the IoT, there was a movement called the Internet of Appliances. The blockchain has been around for seven years already. In other words the long run is a very important factor in assessing the timescales of disruption. In these long periods entrepreneurs rightly build hypotheses about what might work in the market under changing economic conditions. They test and they fail and they build experience and eventually produce the right product or service.

The long run is a very important factor in assessing the timescales of disruption.

Disruption factors:

- Ideology of change

- Global, free distribution

- Self-funding, capital-free

- Meritocratic organization and values

- Strong trust factors based on an open-source method

- Widely distributed information and close connections

- An underlying loss of faith in growth and perhaps even in progress as the economic motivation switches from “grow” to “disrupt everything”

The new impact of globalism

Global connectivity is driving a new level of growth velocity for companies that see its implications. The world is less globalized than we often imagine but that will change as global mobile networks make interconnectivity pervasive and simple. Right now many institutions like banks are generally non-global, relying on networks of correspondents, partners, and distributors to establish presence in major economic centers. Many services are similarly regional and local. But the big disruption will come when more enterprises figure out genuinely global — and often mobile — services or figure out how to capitalize on global-mobile service suppliers.

After Google in search and Facebook in social networks, Netflix is the canonical example of this change, basing its service on the rollout of the new global telecoms infrastructure and device-centric culture. Through video streaming Netflix is able to contain many costs associated with entertainment distribution such as national sales offices and the loss of focus in providing multiple services in the way ISPs have to. Google’s YouTube is warming to this opportunity, too, and Facebook is also a potential player. What’s new?

Disruption factors:

- Global scale reaching billions of customers via mobile connectivity

- Very low-cost operations and, with that, extreme price competitiveness based on new infrastructure

- Strong ease of use and good user experience

- Continuous process innovation

- The development of extraordinary platform experience managing an infinite number of endpoints

The reverse data model

Google and Facebook have successful networks where they control access to their immense trove of user data. But alternative models leave that control in the hands of the individual users, and/or let them use their own data explicitly as currency. Reverse data lies on a continuum that inverts the current marketing paradigm. While Google and Facebook are at one end of the continuum, at the other are phenomena like BYOD, social media, and participation platforms like Chaordix at Lego or Procter & Gamble. Increasingly, data only makes sense if it enables end users.

The reverse data model — Harvard University’s Berkman Center codifies it as ProjectVRM— proposes that banks, retailers, or third parties manage data on behalf of consumers and seek ways to aggregate purchasing intent in order to force down prices. Apple has already signalled that it sees its role in health care as managing data on behalf of customers. Apple and Google may slug it out on data ethics, and the beneficiaries here will be startups who offer to use the web to organize nodes of consumer power.

Increasingly, data only makes sense if it enables end users.

Disruption factors:

- Regulatory forces in opposition to oligopolies

- Maturity of reverse data options

- Consumer budget constraints that encourage them to seek discounts or other benefits through better controlling their own personal data

By Haydn Shaughnessy

About the author

Haydn Shaughnessy is also the author of Platform Disruption Wave, Shift: A Leader’s Guide to the Platform Economy, and The Elastic Enterprise, and a former editor of Innovation Management. He writes about platform disruption at haydnshaughnessy.com.

Haydn Shaughnessy is also the author of Platform Disruption Wave, Shift: A Leader’s Guide to the Platform Economy, and The Elastic Enterprise, and a former editor of Innovation Management. He writes about platform disruption at haydnshaughnessy.com.