By: Doug Collins

Engaging in collaborative innovation by participating in activities such as ideation challenges can put community members at odds with the carrot-n-stick incentive and power structures that exist in every organization, including those that ostensibly support a culture of innovation. As the sponsor of your organization’s program for collaborative innovation, you can structure rewards in ways that give your community members the space and resources they need to pursue ideas to fruition. In this article, community architect Doug Collins helps you think through the process of defining a rewards structure for a basic ideation challenge that respects the innovators and collaborators who contribute.

Thy Just Rewards

One of the most fun and, at the same time, most revealing moments in my dialogue with the client comes when we discuss rewards. That is, let’s imagine that the ideation challenge meets or exceeds its targets. Who benefits? What is the nature of their reward, relative to what they chose to contribute in pursuing collaborative innovation?

Many have written well-researched, insightful pieces on the link between motivation and rewards. See, for example, Daniel Pink’s Drive. Pink covers the topic in an accessible way, synthesizing research in this area from the past 40 years in a way that challenges long-held beliefs on what motivates people to act.

This article, by extension, offers my perspective on the subject from having worked at the coal face with people who apply social media to collaborative innovation in order to realize a larger business purpose or goal. Further, I focus on internal ideation: ideation practiced within an organization, as opposed to with external parties such as clients, consumers, or vendors.

Beyond the iPad and Starbucks Gift Card

My clients serve as a bellwether of what’s perceived as cool at present. Their ideas register on the upper range of the hipster scale. iPads and Starbucks gift cards hold the top two spots by a long, dusty country mile. (Confession: I intend to make a fortune by shorting Apple (AAPL) shares the moment someone suggests bestowing a Droid upon the top innovators in their organization. I believe that this signature event will offer the earliest possible warning of a crack in the otherwise pristine facade of the Jobian Empire.)

Yet, if we were to reflect for a moment, we might observe that (a) the act of rewarding someone participating in collaborative innovation need not—and perhaps should not—represent a singular event in the life of a campaign and (b) the rewards need not—and perhaps should not—center on tangible, extrinsic expressions of recognition. The broader research as related by Pink and as conducted by others backs the latter point.

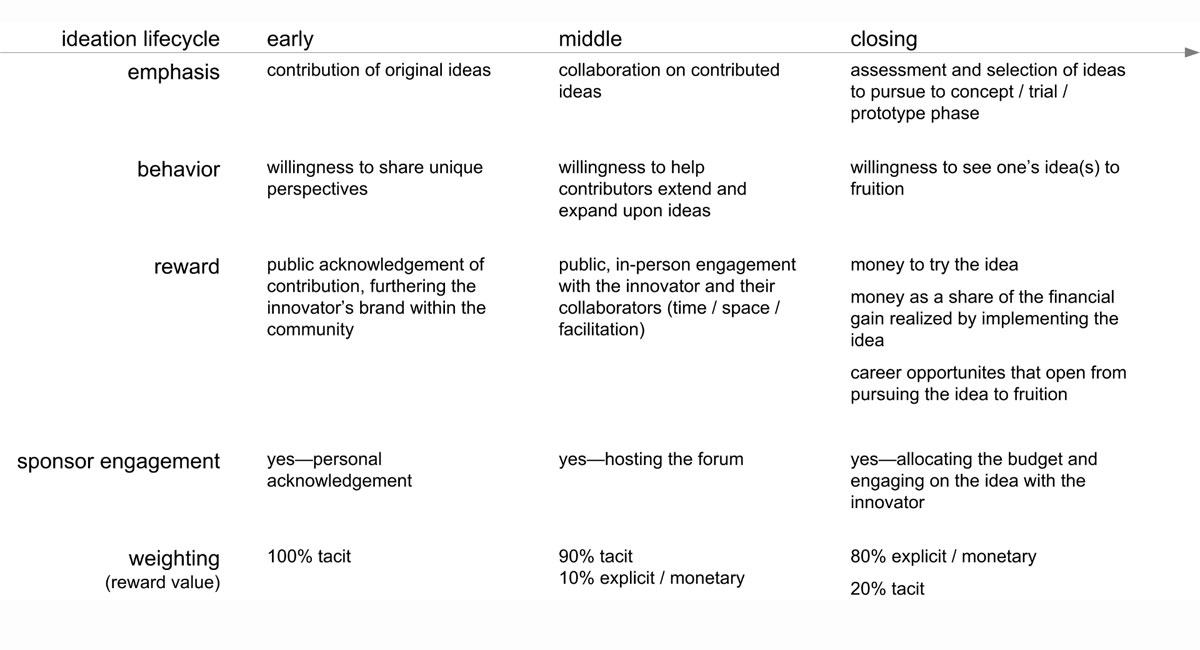

Let’s dig deeper. Figure 1 outlines the discussion that follows on mapping your rewards plan with your goals for each stage of the ideation process.

Figure 1: the nature of the reward as a function of the ideation lifecycle

Go Long, Go Wide

First, let’s consider the fact that most ideation challenges—those activities with a definite beginning, middle, and end—span weeks to months. Further, the nature of the community members’ exploration evolves over this time. Reward and recognition schemes should map to the challenge timeframe and to the activities that typically occur at each stage.

For example, people who sponsor ideation challenges tend to want to encourage contributions in the form of ideas at the start of the event. To this end, you may want to set a recognition milestone at week two (2) of the campaign, acknowledging members who contribute the most compelling ideas, as evidenced by the community through the buzz factor of the ideas and the reputation of the contributors.

What might this recognition look like?

On the intangible front, you may want to feature your top contributors in your program’s innovation newsletter. Ask them the critical questions and help them to articulate responses to…

- What is it about the challenge that resonates with them?

- To what do they owe their wealth of insights?

- What reservations do they (or did they) have about contributing?

- What have they liked and disliked about engaging with the community on their ideas?

Likewise, arrange a simple conference call with the top contributors and the sponsor. Give the contributors an opportunity to share their insights and to gain visibility within the organization, without unduly burdening them by expecting them to prepare elaborate presentations for an executive audience. Coach the sponsor to ask questions and share insights on how they perceive the ideas relating to the critical questions facing the organization.

These approaches offer two benefits. First, you offer your top contributors welcome visibility across the organization. Career-minded individuals value this type of positive exposure. Second, by publishing the leaders’ secret sauce for contributing, you help other members of the organization model the same behavior: if that guy can do it then so can I. The sponsor’s involvement signals that innovation is everyone’s day job.

By contrast, resist the urge to reward members by the sheer number of their contributions and to offer extrinsic rewards. This path encourages quantity over quality and short-term over long-term thinking.

For the Price of a Cup of Coffee

As the challenge progresses sponsors want people to focus on building and assessing ideas that have already been contributed. Here, you have the opportunity to reward a new sector of the community. Some people prefer to build on existing ideas, helping the contributor expand upon and extend their thinking, as opposed to tackling the blank sheet of paper, directly. By bringing their gifts to the table, they help the community evolve an interesting idea into a compelling one. Recognize them.

You may, for example, want to host “idea banger balls”—breakfasts where the idea contributors and their collaborators meet in person to continue working on the concept. You want to have the challenge sponsor host the breakfast. You also want the challenge sponsor to participate.

For the price of some decent coffee and croissants from the locally owned bakery down the street, you realize two benefits. You increase the odds that the people interested in pursuing ideas together cement relationships they will need in order to realize their potential. You likewise energize the innovator to keep pushing forward by connecting them with people who share their enthusiasm and motivation.

To this end, you may want to facilitate games such as Affinity Mapping, The 5 Whys, or The Blind Side, as described in the book, Gamestorming, as a way to encourage this sort of collaboration at your breakfast. Mastering and sponsoring these types of collaborative activities are one of the gifts that you, as the challenge manager, bring to the table as a reward for the community. Do not disrespect the group by holding them hostage with PowerPoint.

Members of your innovation program team who feel compelled to distribute Starbucks gift cards like plastic manna from ideation heaven could do so here as a general “thank you.” You want to have the sponsor hand people their rewards as a form of public acknowledgement. Phoning or emailing in one’s gratitude serves poorly as a tacky alternative.

From Intangible to Tangible

Later in the campaign, the rubber meets the road. Your challenge sponsor and their core team identify those ideas they want to pursue with the community. Here, the intangible must become tangible on two fronts if you want this group of people to participate in ideation with you again.

First, it is often the case that ideas require resource to bring to fruition in order to validate and realize their expected benefits. Allocating the time and money innovators need to test a concept will require the organization to make hard choices in terms where it invests on the front end. At times, deciding to exercise the patience needed for the innovator to fully explore the potential their idea represents turns out to be the costliest choice in environments that reward short-term thinking. If you want to foster a culture of innovation you will keep this commitment on behalf of the organization.

Here, I sometimes get the question of, well, what if the contributor does not want to see the idea through to its logical conclusion. To which I say: baloney. Anyone who embraces innovation to the extent that they not only contribute an idea, but also the idea that the community and sponsor identify as the most compelling will want to pursue it further. Enabling them to enjoy the autonomy to do so serves as a powerful reward.

Second, once the organization validates that the idea provides value and can quantify the benefit, the organization must commit to sharing the financial reward with the innovator (e.g., perhaps some percentage of the net present value of the projected return from implementing the idea over 3-5 years). Some organizations hesitate to place a monetary value on ideas, observing legitimately that the benefit can be difficult to quantify, especially when they improve a small part of the larger value chain from firm to client.

My advice: try. Finance is not an empirical science in practice. Your organization estimates, assumes, predicts, and out-and-out guesses to get through the quarter. Please talk to the people who manage sales pipeline for your organization, for example. If you defer, then you risk disengaging or losing the very people who you want to contribute: your top innovators. The literature on this subject will indicate that, once properly compensated, people will not be motivated by additional financial incentives and that, in reality, these incentives can encourage the very behavior you want to retard (e.g., short-term thinking).

Yet, common sense and basic fairness argues for parity. That is, if the person’s idea provides a projected net present value to the organization of USD 1M over the next three years, then rewarding that person with a dinner for two or a premium parking spot in the employee lot for the coming month runs afoul of recognizing people for the results the produce. By the same token, setting a significant, yet static reward ahead of time (e.g., “USD 10,000 for the winning idea”) will demotivate your members—or motivate them for the wrong reasons—per Pink and company. You risk receiving ideas that have a maximum value to the organization of USD 10K, whereas your community may have produced USD 10M ideas.

Organizations that aspire to create a culture of innovation acknowledge the value that their innovators bring to the table, particularly when their innovations disrupt the status quo. Sun Tzu would perhaps share this perspective, where the problem to be solved through innovation serves as the enemy in this context…

For them to perceive the advantage of defeating the enemy, they must also have their rewards.

Sun Tzu

A Culture of Innovation

In closing, take the following steps in defining rewards structure for your collaborative innovation program:

- Familiarize yourself with the latest thinking on the role rewards play in motivating people—particularly people engaged in creative work such as collaborative innovation. Start by ordering a copy of Pink’s Drive.

- Think through a day in the life of your ideation campaign. What behaviors do you want to encourage at each stage? Map your tangible and intangible rewards to each stage, accordingly.

- Do not steer away from creating a model by which you can estimate the economic value of the innovations that you, or the organization at large, choose to pursue as an outcome from the ideation challenge. You need to have this insight at hand, regardless, to help convey to your own sponsors why having the organization engage in collaborative innovation makes sense. Your work here serves double duty in calculating reasonable, tangible rewards for ideas that materially benefit the organization.

Rewards send a powerful signal about the behaviors your organization encourages. What does your rewards structure say about your organization’s commitment to encouraging a culture of innovation?

By Doug Collins

About the Author:

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He has served in a variety of roles in helping organizations navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by creating forums, venues, and approaches where the group can convene to explore the critical question. He today works at Spigit, Inc., where he consults with Fortune 1000 clients on realizing their vision for achieving leadership in innovation by applying social media and ideation markets in blended virtual and in-person communities.

Doug Collins serves as an innovation architect. He has served in a variety of roles in helping organizations navigate the fuzzy front end of innovation by creating forums, venues, and approaches where the group can convene to explore the critical question. He today works at Spigit, Inc., where he consults with Fortune 1000 clients on realizing their vision for achieving leadership in innovation by applying social media and ideation markets in blended virtual and in-person communities.

Previously, Doug formed and led a variety of front end initiatives, including executive advisory programs for industry influencers, early adopter programs for lead users, corporate strategic planning, and structured explorations of new market and product opportunities. Before joining Spigit, Doug worked at Harris Corporation and at Structural Dynamics Research Corporation which is now part of Siemens Corporation.