By: Haydn Shaughnessy

In this in-depth article Haydn Shaughnessy discusses why traditional ROI decision making is becoming irrelevant and how options planning is a key element of competitiveness. In these uncertain times firms need to recognise and analyse their options thoroughly in order to be ready for inevitable change.

In the first part of this series I looked at a few ways to assess the disruption potential of an industry. There’s much more to be said about that, and about disruption planning, but rather than return with more detail, I’d like to talk about options planning as a key element of competitiveness.

In a 2014 study of 30 companies in transition I found that the majority of them made their innovation decisions using traditional, financial ROI criteria. Surprisingly only 5 companies made investment decisions based on the desire to explore new revenue streams. 9 counted “adding to the company’s foundational capabilities” as a criterion that would help in securing budgets. Even in these cases, however, the primary criterion was a clear financial ROI.

In a 2014 study of 30 companies in transition I found that the majority of them made their innovation decisions using traditional, financial ROI criteria. Surprisingly only 5 companies made investment decisions based on the desire to explore new revenue streams. 9 counted “adding to the company’s foundational capabilities” as a criterion that would help in securing budgets. Even in these cases, however, the primary criterion was a clear financial ROI.

What is wrong with this situation? I think there are three things and they need to be addressed:

- It is contradictory to expect people to create change if they are constrained by financial ROI. It’s the kind of thinking that encourages fail-fast, fail-cheap innovation, which I think of as a way to look busy without necessarily changing much.

- Companies need deep process change or “process model innovation”. Sometimes that need gets hidden in the shade of digital transformation. Yes, digital is important but experience is showing us that it is areas like decision making that matter. You can be digital and make good or bad decisions, in good or bad ways.

- Good firms have traditionally created many options that went nowhere. In past versions of this idea, Nick Vitalari and I claimed optionality was a new element of strategy. In fact, all the great engineering firms had their engineering benches full of pet projects that employees would be working up, long before we heard of Google’s 20% time.

It is contradictory to expect people to create change if they are constrained by financial ROI.

As market disruption happens in real time, developing strategy in response to competitive threats becomes more difficult. That’s one reason why Rita Gunther McGrath claims there is no competitive advantage left.

It is better to have options already in the locker ready to play out. A recently released YouTube video of Steve Jobs speaking to Apple employees just after he returned to the company has him underline the fact that he has just cancelled 70 R&D projects. What’s so interesting about this, is that it is a rare insight into the level of project investments the company makes. If you can clear 70 projects then you have many more on the bench, and indeed they did (digital cameras, miniaturization of computers, chop design and so on).

This notion of having multiple options ready-to-go is an important part of responding to disruption. It requires changes to the way companies make decisions and how CFOs account for research and development activity. It’s increasingly important to have projects which won’t materialize into the market and these can’t be done on the cheap.

In the past I have used ETwater, a small Novato-based company that makes irrigation systems for parks and landscapes, as an example of strategic options planning. Nick and I used Apple – and the huge range of options it had at the time of the iPad 2 launch. But people tire of having to live up to Apple’s qualities. In this article I will use the more generic case of automating outdoor services and call the company: Garden as a Platform.

1. Creating options strategies

Garden as a Platform has been attempting to harness a platform strategy. Its ambition is to disrupt the whole sustainability supply chain by introducing Cloud-based services where mobile apps can interact with physical systems like sprinklers and sophisticated data. Think of it as Nest but instead of being a trojan horse for the smart home, i.e. the thermostat being the first point of entry for multiple smart home services, Garden as a Platform is an irrigation system that catalyses smart services for the outdoors.

The system is intelligent in that it can combines plant data, soil data, solar irradiation data, wind, rainfall and humidity data, and environmental data to the exact conditions needed by your plants.

By creating intelligent water management for urban areas Garden as a Platform offers the possibility of reduced costs and increased yield on urban landscapes or in leisure spaces like gardens.

One of the characteristics of platforms is they allow executives to move horizontally across products and services.

That is its core product. And it could stay there, just like Net could remain a nice looking thermostat, linked to the mobile. But one of the characteristics of platforms is they allow executives to move horizontally across products and services. At this stage Garden as a Platform could seize the high ground in irrigation systems by being the first truly smart one. It could produce modular systems that other garden services connect with – security, lighting and ponds are obvious examples but perhaps there are other services or products that perhaps we haven’t yet thought of.

What is fascinating about it is the process of introducing modern concepts to activities as traditional as growing plants. In this field of endeavor most products have been pretty dumb. That’s changing. Sprinklers with timers are commonplace. There are now other “Nest-like” entrants in the domestic irrigation market – companies like Blossom and Skydrop both of which have simpler propositions targeted at the home – save water through the use of smart sprinklers linked to weather forecasting.

Garden as a Platform is more sophisticated in that it doses for specific vegetation as well as for weather conditions. And the company has created its platform by incorporating an ARM processor into its own sprinkler controllers, which it has opened up to developers with a SDK and API.

At one point the company contemplated heading in the direction of a marketplace – a market for garden-related services that would make use of keen gardeners to supply garden services in their neighborhood.

The company has multiple market segment possibilities – landscape managers, commercial property owners and domestic property owners, in conditions of worsening drought.

Let’s summarize the optionality that Garden as a Platform has created:

Table 1 Strategic options for Garden as a Platform Inc

| Strategic option | Development options | Revenue sources | Ecosystem |

| 1.Try to redesign the supply chain in landscaping (domestic or professional) with smart connectable sprinkler system to support dosage | Focus on connected devices in the outdoor area; create the indoor-outdoor link | Hardware | Device makers, chip makers, and embedded processors |

| 2. Focus on either professional or domestic market | Very low cost (needs astute sourcing strategy) or high cost components | Hardware | Landscape gardeners or hobbyists |

| 3.Focus on AI and intelligent handling of data to inform gardening/landscaping community of options | Integrate multiple data sources; create Cloud delivery capability | Sell kit, sell subscription, sell app upgrades, sell data to specialist growers | Secure partnerships with data providers |

| 4. Create connected outdoor system | Build and distribute mobile apps to control irrigation, lighting, ponds, security | Apps, upgrades, SDK, subscriptions | Create developer ecosystem to implement an unknown variety of new features |

| 5. License technology | Become the design centre for outdoor smart technology | Royalties | Everybody |

| 6. Create marketplaces | Build transaction engine, build or offer community platform | Control cashflow; take % on field service or domestic garden services | Public, specialist garden management suppliers |

In fact, all these things are possible. The number of revenue opportunities magnifies as you go down the table. In addition, the company could pick out market segments as other options – different sizes of landscape, domestic, professional and so on.

Platforms substantially increase the options that are available to companies. They also imply cost and it is important to consider that in each of these options there are many development and marketing costs that need to be mitigated by very smart decision making.

Substantially more planning and analysis is involved when a company chooses to be disruptive.

In devising disruption strategies it is important to lay out the top-level options as we have done above.

But it is clear that what stems from this is that substantially more planning and analysis is involved when a company chooses to be disruptive. More options means more probing. More setting out the pathways. What’s also clear is that using a version of lean innovation is probably not going to cut the planning cycles and may even be impossible, given the complexity that options bring.

It is also worth remembering that even the best companies that enter into the cycle of product, data and platform planning can get it badly wrong – as evinced by the failure of Google Glass.

It is very likely that all teams will ultimately build on trust or faith, sure (sort of) that they have a strong hunch about the market, and know their own level of dedication and application will pull them through difficult times. Still they need some way to value the different options in front of them.

Mikael Collan at the Lappeenranta University of Technology has proposed a different way to approach these challenges. Not MVP, not lean but perhaps a bit better than gut instinct.

Collan’s contention is that many of the tools designed for assessing long term investments or R&D investments are too complex to use.

Putting together the various objections to traditional financial ROI the summary is:

- They call for certainty when we know for a fact that production development is uncertain

- The tools, once you move past discounted cash flow, are too complex for many teams to use, hence the easy, certainty-based tools remain in favor

- A lean iterative approach might be sensible but can also slow projects where there is complex optionality and very often there is a need to commit to a substantial project well in advance of a few iterations with customers.

2. Platforms and Options Analysis

2.1 Pathways

If we take one option from the table above it is also clear that many of the features of the table need to be extended to begin any kind of cost and value analysis. Each element is very high level.

| Strategic option | Development options | Revenue sources | Ecosystem |

| 6. Create marketplaces | Build transaction engine, build or offer community platform | Control cashflow; take % on field service or domestic garden services | Public, specialist garden management suppliers |

Building a transaction engine means making many decisions about the types of payment systems to accept and beyond that to interface with; as well as an architecture that would allow the flow of funds to scale and to adapt if, say, there was a rise in the use of digital currency.

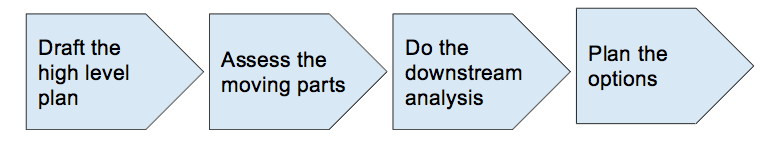

The major pathways involved in just this final area need mapping out. I think there are four.

1. The high level plan

|

|

2. Identify the moving parts

Which of these factors matters most because it is most liable to disruption or simply going off the rails? For example, the payment options and initial testing are not going to evolve dramatically. However, those like developing community and the development of trust are likely to be very dynamic, while people may react against some kinds of rule setting. The real moving parts appear to me to be:

Disruptable areas

|

And areas prone to error

|

3. Do the downstream analysis (see below)

We will come back to the downstream analysis shortly, but for starters there are some high-level questions that can be asked of the moving parts.

What happens in the event of a poor transition from the initial traction plan to scaling the marketplace? How can this be anticipated sufficiently in advance? What is the likely cost? Who will manage the talent pipeline with a view to having HR options?

What happens in the event of a reputation damaging incident in the first six months? What is the likely cost of this and what are the software contingencies to overcome it?

Under what conditions should the program pivot, say to professional garden services providers only?

4. Options plans

From that analysis comes the kind of options plans that you want in place before starting. Say there are three of these:

- Only allow professional gardeners to offer services on the platform

- Allow anyone with demonstrable skill

- Gravitate from professional to anyone after a proving period

It should be clear that developing a minimum viable product is probably not going to help create the proof points that would be needed for this type of project. The chances are that MVP will help in ascertaining which interface designs work best, though A/B testing could achieve that too. Similarly, a traditional business plan that set out assumptions about numbers of users could build confidence but the confidence could be false.

But to get to points 3 and 4 more work is necessary including:

User analysis & Pathway analysis

2.2. User Analysis

In traditional business planning the objective has been to reach an agreement about potential revenue yields or cash flow and margin. In lean innovation the plan unfolds as the minimum viable product grows its user base. But the luxury of iterative development is not always there. Many people have to make a call on investments long before they feel secure about it.

In a real options exercise the analytical concerns are different. The first is what can I say about the value I am adding to any given class of customers? The second is what can I do to anticipate the need for change.

The first of these can be addressed through a combination of any kind of customer research (focus groups, MVP, market analysis) and an assumption that users generally want to easiest possible solution, i.e the one that involves them in the least effort.

In that sense Uber is the perfect solution to what Collan calls lazy-user analysis. In the case of an Garden as a Platform or any service, one could say much the same. The idea of a service is to provide value to people who are already overwhelmed by complexity. Assume that for many, the lazy option is the best option providing the price is within acceptable bounds.

The issue of pricing is more difficult. Many people will pay a premium for a brand that is disproportionate to any of the material inputs (like the quality of materials). This intangible brand promise is something that brand companies have a long history in evaluating.

In a platform service the analytical step is to ask what range of needs do customers genuinely wish to see delivered? In the market for automating the outdoors that might be:

- Automate water dosing (rather than just automate watering)

- Automate all watering

- Signal the need for follow up actions (such as weeding or fertilizing)

- Automate information flow (e.g. hyper-local weather, appropriate plants per soil type)

- Provide information for planning of green space

However, there would appear to be one other lazy user option. Get other people to do the garden. There seems to be a good prima facie case for lazy user garden services.

However, they don’t seem to revolve around automating the outdoors. In fact, the two are potentially conflicting approaches. The gardener who wants good information about soil type and appropriate plants is probably not the gardener who wants to foist the work off on other people.

Where does the value lie then? In reality we know people have a mixture of reasons for engaging with platforms and they all need to be explored:

|

Information access |

Pleasing experiences |

Sharing knowledge |

Connecting with people |

Earning spare money |

Deals |

Convenience |

These types of motivations all help to shape the value that a platform can consider offering:

- Information remains important to the committed gardener

- Information could be an important asset that the lazy gardener could share with a small service provider

- Shared virtual spaces where lazy gardeners and small service providers could exchange information could be built into the app, a Dropbox for gardening information exchange

- Beauty could become a theme in the content plan as most people like to share photographs

- Photographs could be the medium for progress reporting

- The overall data system could professionalize the small local service provider improving her potential for income

- Automation becomes a cost saver and part of the background of garden maintenance but not the main show.

- The issue of price remains sensitive but in the case of sharing economy labor there is an assumption of low price. Pricing would more than likely be dependent on the enjoyment the service provider gets from the job along with the opportunity to learn.

However, there still needs to be some analysis. Any single service could be the topic for a discounted cash flow analysis but we’ve already said that is not necessarily the best way forward.

2.3. Doing possibilistic analysis of pathways

Real options analysis originates in technology and capital investment planning, where it plays the role of putting solid figures on a long term investment. However, that idea of “solid figures” needs qualifying. Long term investments typically introduce uncertainty and uncertainty is now integral to even short term decisions.

Collan suggests that the fatal error of much planning is in characterizing the questions and decisions as matters of probability. We do a lot of analysis about probable outcomes. What we know of probability is that most startups fail, so a probabilistic solution is not to begin. But people are attracted by possibilities so we need to do more possibilistic analysis.

At this stage we have some sense of what engages users or why they gravitate towards platforms.

We also have some sense of the kinds of downstream roadblocks or hurdles we may need to navigate around.

In a discounted cash flow environment we would be making an assumption about the ultimate revenues flowing to the platform in year five and modifying this in the event of these foreseeable problems (though in many corporate instances we would ignore any that were too damaging to the cash position).

How can we make the analysis more realistic than discounted cash flow and keep contingencies front of mind? It seems to me that a planning process can make use of cash flow assumptions and that the contingencies should be a crowd-sourced piece of knowledge. Let me elaborate on that.

It is worth plotting out what it takes to make the conditions for a market to work.

Scenario 1: Strong conditions for the market to work

| Lazy user | Cheapness | Trust in service provider | Convenience | Shares images |

| Hobbyist | Revenue | Paid automatically | Low hassle income | Learns from the data |

Suppose these and other conditions are adequately met – how would be modify the assumptions of success to make a cash flow realistic?

Collan argues that in most cases the outputs of an investment will have a distribution from worst case to best case and over time experience will close the gap in knowledge between the two. My interest, in discussing this with Mikael, is to find a way to modify assumptions, say, in this case, the assumption about when a project will gain traction.

There should be a variety of reasons why it will, given that you have a strategy but how does the crowd think about that? Managing reputation well for example is an aspiration but it takes only one rogue newspaper story to create the damage.

Table 2. A Sample Possibility Analysis for Meeting Traction Targets for Garden as Platform at 12 months

The scores are %; they are based on the aggregrate crowd score of what is fully possible or what has low possibility. There is then a score for likeliness, and divergence score. It is also possible to introduce an uncertainty score.

| Fully possible for us | Lowest possibility | Likely | Divergence | |

| Talent and talent pipeline problems | 60 | 20 | 50 | 40 |

| Poor evolution of community | 40 | 24 | 30 | 16 |

| Reputation and trust | 70 | 20 | 35 | 50 |

| Poor content adaptability | 30 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Architecture | 25 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Cyber-security | 80 | 0 | 40 | 40 |

| Average | 51 | 18.5 | 32.5 | 27 |

The table is intended as a check on discounted cash flow honesty. By focusing people on what is possible rather than probable it highlights the extent of potential problems. What it says is that Garden as Platform stands a fairly high chance of being derailed by talent problems or the poor evolution of its community efforts or even reputation, trust and content plans, as well as cyber security.

In these instances, going back to the initial strategic options table it becomes apparent that yes indeed Gerden as Platform has many options but once it starts to dig in it sees that each option has substantial risks. However, it also has three other advantages:

- It knows what those risk are, more or less quantified

- It can start to determine when those risks might arise

- It can begin to re-discount its financial expectations based on the assumption either of lower revenues or more expenditure to counter risk

- And it knows that if it goes the full platform journey it will have its work cut out because there is an assumption implicit in all this that it will continue to do excellent work in hardware design and advanced data applications

So going back to the earlier point, the options now start to look like:

Try to recreate the supply chain in landscaping and gardening but be cautious about doing it as a marketplace for people.

3. Analyze Process Implications and Organizational Change

In the Garden as a Platform example, several new processes become apparent:

Seeking participation/ecosystem

The real option analysis has shown Garden as a Platform potentially heading into trouble if it attracts a niche urban landscaping market when what it really wants is a rural/semi-rural market that requires more apps and more sensor-based devices to do precision water delivery. In the analysis the wrong ecosystem may be evolving. But its real options strategy allows it to course-correct.

Information building

To keep on its growth track, Garden as a Platform has to go beyond marketing, to building relationships across the layer or network of people that influence decisions: VCs, reporters, rural cooperatives, social media influencers etc. It finds it has to invest in more than

Just collateral – it has to be present, it has to develop different content types, it needs thought leaders who are credible in its broader market but it also needs high level relationship builders who can help validate its approach in the VC/blogger community. That way, its story doesn’t just get out – it gets out in ways that are validated

Feedback management

It also needs an operations executive (COO/CFO) who can manage the feedback loops inside the real options model and make sure these are translated into operational capabilities like reacting fast to new information needs, hiring in requisite skills, providing customer incentives, changing or reinforcing the revenue model at critical junctures etc.

Conclusions

In these few pages I have tried to give a sense of why traditional ROI decision making is becoming irrelevant. That is not to say that people don’t want to make money. It is more to say that increasingly companies are having to place their bets. Times are very uncertain. In placing bets they should be as informed as possible and that involves the steps I have described here Articulating options, analyzing them thoroughly and therefore being ready for change.

By Haydn Shaughnessy

About the author

Haydn Shaughnessy is regularly described as “one of the most refreshing thinkers on innovation.” Haydn is one of the pioneers of platform thinking and how business platforms are disrupting the global economy. He help leaders understand the disruptive power of platforms and ecosystems in reshaping markets and enterprises.

Haydn Shaughnessy is regularly described as “one of the most refreshing thinkers on innovation.” Haydn is one of the pioneers of platform thinking and how business platforms are disrupting the global economy. He help leaders understand the disruptive power of platforms and ecosystems in reshaping markets and enterprises.

Haydn is the author of Platform Disruption Wave, Shift: A Leader’s Guide to the Platform Economy, and The Elastic Enterprise. He is a regular contributor for Innovation Management, Wall St Journal, Forbes.com, Harvard Business Review, Irish Times, Times, GigaOM, and many other newspapers and magazines. He writes about platform disruption at haydnshaughnessy.com.